“When the actor performs badly, then you see the truth of the film”

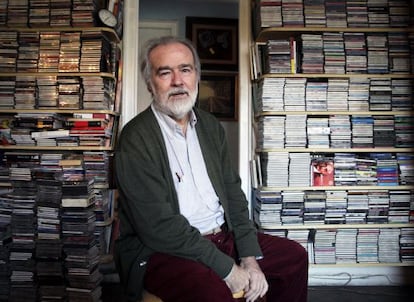

Filmmaker and professional gambler Gonzalo García Pelayo is releasing his first movie in 30 years The premier is coinciding with an in international revival of his work

First it was the artist and cultural mover and shaker Pedro G. Romero, then the film magazine Lumière and, now, Vienna's Viennale festival, the Seville European Film Festival and the Jeu de Paume art center in Paris. The revival of the work of Gonzalo García Pelayo, one of Spain's most iconoclastic and unorthodox filmmakers, 30 years after it fell into neglect, is one of those lucky events in life that ought not to surprise too much a man who now makes his living as a professional gambler.

So, what does Gonzalo García Pelayo now consider himself? A filmmaker, he replies: he always has been and always will be, despite the fact that the vast majority know him as a music producer or as the inventor, along with his five children, of a legal system for beating casinos. His gambling adventures were told in the film The Pelayos, released last year and directed by Eduard Cortés, but his passion for cinema, which took root much earlier, was something that not even his own offspring knew about. "I didn't bug them with my frustrations," he explains. "I felt banished from cinema, abandoned by it. If nobody understood me, why was I valuing it? It's only now that I thought they should be seen."

As a young philosophy student in Seville he decided to go to Paris in order to prepare to attend the now legendary Official Madrid Film School. "Alfonso Guerra wanted to go and they wouldn't let him in. When the school closed because of a strike mounted by the Communist Party, deep down I was glad. I felt you didn't learn anything there."

Between 1976 and 1982 García Pelayo directed five films - Manuela (1976), Vivir en Sevilla (1978), Intercambio de parejas frente al mar (1979), Corridas de alegría (1982) and Rocío y José (1982) - but then fell into obscurity until his films started to be championed decades later, especially his cult movie Vivir en Sevilla , as part of an Andalusian countercultural movement that emerged during Spain's transition to democracy and faded at the end of the 1992 Seville Expo.

Gambling on the big screen again

Vienna has always smiled on the García Pelayos. Ten years after Gonzalo García Pelayo and his team, made up of his sons and nephews, won 78,000 euros in a single night at the Vienna Casino, the Spanish director's first film in 30 years is being screened at the city's Viennale film festival, alongside a retrospective of his previous works.

Alegrías de Cádiz is a blend of documentary and fiction, without professional actors and made for a song, with the aim of transmitting the color of the city's fiestas. The Metro Kino cinema, a few steps away from the Vienna Casino in the city's old quarter, was full for its premiere.

"For me, this moment is better than the night of the [78,000 euros]. Alegrías de Cádiz was finished with Vienna specifically in mind. After finding out that the festival was interested in my films of more than 30 years ago, I thought it was important to show signs of life. Luckily I am alive, although I had a heart attack a few years ago, and I wanted to show that I can still make a movie," he told EL PAÍS enthusiastically.

García Pelayo's movies from the 1970s and 1980s were not box office successes and were swiftly forgotten, but a renaissance of sorts came in 2012 when the documentary The Pelayos was made. In it, the story is told of how the family developed a system of measurement and calculation to beat roulette wheels across the world.

Propelled by this happy return, García Pelayo - the phoenix of Spanish cinema according to Le Monde - has come back to direct Alegrías de Cádiz, which was projected in Seville on Thursday following its premiere several days ago in Vienna.

He was inspired by the love of the city that fed him "spiritually" and the same esthetic approach of his previous films: technically precarious, impure, as wandering and free as they are artificial and fake, pegged to a reality that breathes, full of music and words, and championing mistakes as virtues. "When the actors perform badly I like them a little bit more," he says. "And that is neither a joke nor a boutade. I like the person much more than the character. And I like the actors more than what they are interpreting. In some way it is as if the veil had fallen down, when the actor performs badly you see the truth of the film."

It's that experimentalism in a deserted film scene that in some way links his movies with those of many young filmmakers today, who whether out of necessity or vocation are drawing on the esthetics and ideals of the 1970s. "That cinema was buried by [director and former Spanish film chief] Pilar Miró," he says. "She wanted to make high-flying cinema, to create a big industry in which there was no room for a certain kind of small cinema. Years later they told me that she even opposed a prize they were going to give to my last film, which for me then would have been very important because it would have allowed me to go on directing. In short, I was bored of making films that didn't interest anyone and that when they reached the administration bumped into a bottleneck that was only open to big projects. I think many of us ended up in that ditch. But I don't like to complain, and even less place the blame on the administration; the reality is we have what we deserve and we are not interested in them or anyone else."

García Pelayo smiles and finishes with the help of a line by Silvio, legend of the Seville underground rock scene who also features in Vivir en Sevilla. "Hey, I will never be a protestant."

The esthetic ideals of his cinema are basically economic ones: "To be able to shoot with little money. That is something that definitely does not create an industry, and in that Miró's idea did make sense. But I also think that, unlike Portugal, we were not capable of accepting our economic smallness and the megalomania has finished Spanish cinema off, even though we have some great directors of photography."

He says that his masters are Truffaut and Godard, that his favorite film is Raoul Walsh's Gentleman Jim, but deep down he would like to be seen as "that Spanish filmmaker they sought for desperately in France, the missing link between Buñuel and Almodóvar."

Banned from setting foot in casinos and dedicated to betting on horses, soccer and tennis, he maintains his own ambiguous faith in the future: "I am an individualist. I have spent so many years thinking about Spanish cinema and without clearing that up I only know that I will make films until I am 130 years old, but I will live off the bets."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.