“If the right had done the cleaning up, Spain wouldn’t be so authoritarian”

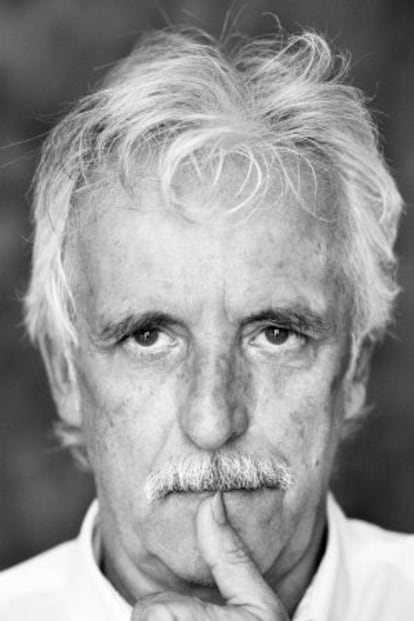

The famous musician discusses the state of Spain's political system and SGAE

One of Spain's most respected pop musicians, José María López Safeliu, better known as Kiko Veneno, has enjoyed a long, and in creative — if not commercial — terms, fruitful career, working with some of the biggest figures on the Spanish music scene over the course of four decades.

Born in Figueres, Catalonia, in 1952, he grew up in Seville, where he absorbed the city's rich flamenco traditions. After finishing university, he traveled throughout Europe and the United States for a couple of years, until in 1975 he met flamenco/blues pioneers Rafael and Raimundo Amador, forming Veneno. In 1977, they produced Veneno, their only album, one that would influence a generation of musicians, and is still considered an essential part of any Spanish pop collection.

Veneno had split up by the time the album came out, and Kiko began a solo career that has allowed him to experiment with different sounds and work with many musicians — among them Camerón de la Isla and Paco de Lucía — typically blending the spirit of flamenco with razor-sharp lyrics.

A key figure within the so-called Movida — the late 1970s and early 1980s Madrid-based arts movement from which, among others, Pedro Almodóvar emerged — Veneno has continued to work on his own projects, producing albums intermittently. Last year he was awarded the country's National Music Prize. He has spent much of the summer touring, promoting his album Sensación térmica (Sense of heat).

A long-time critic of the music industry, he opposed the so-called Ley Sinde — the Zapatero government's attempt to crack down on peer-to-peer internet downloading — but is a staunch defender of the SGAE, the performing rights society, which is still emerging from a corruption scandal that came to light in 2011. In July it elected José Luis Acosta Salmerón as the organization's new president. This came only a few weeks after it voted to remove Antón Reixa, who had served for a year. In 2011, Eduardo "Teddy" Bautista, was accused of making 400 million euros "disappear" in a highly publicized scandal. Which is where we begin our conversation: is Spain really more corrupt than anywhere else?

Question. Why are there so many thieves in Spain?

Answer. We've always thought the Italians are a bunch of mafiosi that go round killing people. Hah! That's so old-fashioned, so violent. The Spanish mafia is much more powerful than the Italian mafia because it doesn't need to kill. It has everybody in its pocket. It is perfect. If we uncover corruption in a political party here, we just remove the investigating judge from his post.

Q. What's your reaction when you see the prime minister on television?

A. Embarrassment. I guess the idea is to keep us misinformed, to swallow what they think we need to be told. This doesn't happen anywhere else! And we deserve it. We have swapped music for a military march, information for propaganda, and John Huston for Terminator 4. In the end, it's us who have changed. I think the political transition in this country, after Franco died, has to be seen for what it was: the right wing in this country believed that we were dumb for having put up with Franco for so many years, and carried on punishing us. And we've accepted it.

Q. What about Felipe González and the Socialist Party?

A. The right wing gave him the job of cleaning the country up. "You do it Felipe boy, your dad was a farmer, and you've trod in a lot of cow shit." If the right had done the cleaning up, this country wouldn't be so authoritarian. The Popular Party is a chamber of horrors. They have no human or political worth.

Q. The SGAE has also been shown to be corrupt

A. In the context of Spain, the process has been relatively transparent. The board got rid of a guy they didn't trust. If only Spanish justice was so efficient. The SGAE is under attack. EL PAÍS says it is too big. It generates a lot of money [collecting royalties], and successive governments have been after it for a decade now.

Q. You were awarded the National Music Prize last year...

A. This year they've awarded the Prince of Asturias Prize to Antonio Muñoz Molina, a writer who has been a savage critic of the mediocrity of this country and the dirty tricks of our politicians.

Q. You didn't accept your prize in person, but you took the prize money: 30,000 euros...

A. I didn't want to create a fuss, but I have earned that money a hundred times over. I deserved it.

Q. You're not the typical rock star: married to the same woman for decades, and you never got into drugs.

A. The secret is to do what you can, and to do it as well as you can.

Q. How would you like to be remembered — your epitaph?

A. My songs are my epitaph. So I guess it would have to be "Volando voy, volando vengo" [I'm flying here, flying there]. But, you know, musicians have been granted eternal life.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.