Pedophile was perfect neighbor

Daniel Galván Viña lived a double life for years, abusing children in Morocco, before sparking an international incident when he was mistakenly released from jail

Daniel Galván Viña was well known and liked in Dior Chebbi, a working-class district in the Moroccan city of Kenitra, where he had lived for the last six years. He was regarded as an educated man, well off, somebody you'd want to invite to a family gathering; a man you could trust to look after your children if you went out for a few hours, who would teach them English — in short, the perfect neighbor...

Until one day, in late November 2010, he made a fatal mistake: while away on a trip, he rang one of his neighbors, asking him to destroy several DVDs and a pen drive. But instead, the neighbor sold them to a man called Mustapha Rukzat. When Rukzat discovered the contents (videos and photographs of Galván sexually abusing 20 different children), he contacted Hamid Krairi, a well-known lawyer and member of the Moroccan Association of Human Rights who has represented several victims of child abuse. Krairi went on to spark a political storm that has become known in Morocco as Galvangate.

The case made headlines around the world after thousands took to the streets around Morocco to protest King Mohammed VI's July 30 decision to pardon Galván, along with 47 other Spanish nationals — an annual tradition that forms part of the celebrations marking the monarch's accession to the throne. The affair has embarrassed the Moroccan and Spanish authorities, forcing King Mohammed to rescind the pardon, after which Galván was rearrested in Spain. "It was a great victory for the people. His majesty has had to back down, and the pedophile has been sent back to jail," says Krairi.

A six-year-old told the court he had taped over her mouth to silence her screams

After Rukzat and Krairi had established that Galván was back in Kenitra, Krairi presented a formal complaint to the district prosecutor's office. Two days later, on November 28, the police went to Galván's home and arrested him and searched the premises, where they found a digital camera, a laptop computer that contained the same photos found on the pen drive, as well as others, two cellphones, a wooden dildo covered in red wax, DVDs, and several bottles of wine.

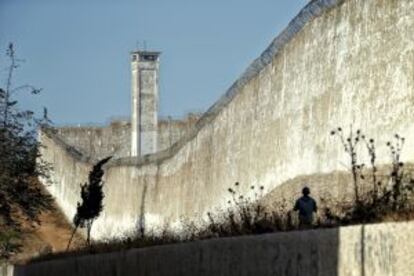

After taking his statement, in which he admitted to indecently touching several children and exposing himself to them, while insisting that the photos were for his own use and he had no intention of distributing them, he was remanded in custody at Kenitra's jail. He would remain there for three-and-a-half years until his pardon.

The Moroccan authorities' records show that Galván was born on July 1, 1950, in the Iraqi city of Basra. Galván told police that he had lived in Morocco on and off since 2004, traveling back and forth to Spain. According to the Spanish authorities he obtained Spanish nationality by marrying a Spaniard. After he was arrested in Morocco in 2010, he told the investigating magistrate that he was divorced, with two children. Despite having lived for more than 25 years in different locations in Alicante, when he was asked by a Spanish judge last week to provide proof that he had roots in Spain, he could only give the name of one friend: Ulpiano.

Ulpiano, who has asked to remain anonymous, lives in a small community on the outskirts of Murcia. He says he was surprised that Galván cited him as a friend. "Of course I know him, I've known him for years, but I wouldn't say we were close," he says. Ulpiano says that during the 1980s, Galván was already living in Murcia, but back then was known as Salah Gabhan Benia. Ulpiano says Galván was his Arabic teacher. "He was clearly an educated man, a man of the world. He speaks French, English, Arabic and Spanish," he says.

Others who met Galván say he told them that he came from a wealthy family in Iraq, that he studied biology at Basra University between 1970 and 1974, that he had been a lieutenant in the Iraqi army, as well as in the navy, but had deserted. "He told us he was a Kurdish refugee, that he had escaped from the army, but he never talked much about politics," says a teacher at the University of Murcia who taught him English during the 1990s. Before arriving in Spain, Galván told people he had lived in Morocco, the United Kingdom and Canada.

By 1992, Galván, now using his Spanish name, had secured a Spanish passport, and in November of that year, his Iraqi qualifications were homologized by Spain's Ministry of Education. He managed to scrape a living teaching English and Arabic, as well as the occasional period working as an agricultural laborer.

In 1996 he secured a grant at the International Relations department of Murcia University, where he remained until 2002, working as an administrative assistant, and liaising with North African and Middle Eastern universities. "I thought he was Lebanese," says Matías Balibrea, his former boss at the university, who says Galván also made extra money giving private language classes. In 2002, when his contract ran out, he assumed he had been sacked, and instead of reapplying for his post, he unsuccessfully sued the university. By now he had taken out a mortgage on a small apartment in the rundown outskirts of the seaside resort of Torrevieja. Neighbors there say that over the following years they saw less and less of him.

Some would take money and keep the offense a secret — that's how poverty works"

Galván's trial began on May 2, 2011 at the courthouse in Kenitra, where he faced charges of unlawful sex with a minor, attempted rape, corrupting minors, instigating minors to commit acts of prostitution, indecent exposure, and exploiting minors for the production of child pornography. One by one, Galván's alleged victims, who at the time of the charges against him were aged between two and 15 years of age, gave evidence against him.

The witnesses said Galván drugged them before raping them, and that when they woke up they were naked and in pain. Others say he threatened to kill them and their families if they said anything to anybody about what had happened, and that he photographed them while the abuse was taking place. One six-year-old girl told the court that he had taped over her mouth to silence her screams.

The medical reports from the Al Idrisi hospital in Kenitra confirmed that seven children were sexually abused and raped. A 15-year-old girl who worked as a home help for Galván, along with her sister, had previously brought charges against him after he allegedly exposed himself to them and attempted to force them into having sex with him, but their parents withdrew the charges after making Galván to agree in writing to marry the eldest and maintain the other. They were then sent back to work for him, and he continued raping them, the pair told the court.

Galván told the court that he was the victim of a "plot to put me behind bars," dismissing the testimony of the children as a fabrication. He said his 15-year-old cleaner had consented to sex, as had another girl. The photos on his computer, he said, had been taken by the children themselves, and that he didn't remember how or when they were taken, or how they had gotten on to his computer. He said he suffered from schizophrenia, which had been diagnosed when he was 47 by a Spanish medic, and that this had forced him to retire. He had been admitted to a psychiatric hospital in 2001 and had suffered his first attack while he was serving in the Iraqi army during the war with Iran, after he was taken prisoner. His arguments fell on deaf ears and the court judged that he had acted with premeditation and was not suffering from any mental illness that could have been responsible for his actions. The state prosecutor called on the court to "apply an iron fist" when handing down a sentence, which the court duly did: he was sentenced to 30 years in prison.

Fast forward to August 6, 2013. Ulpiano, his supposed only friend in Spain, confirms that Galván was diagnosed with schizophrenia, and that he was officially retired and given a state pension. As soon as Galván arrived in Spain after his pardon in July, he went to see the psychiatrist who had seen him before to ask for a new assessment of his mental health. He was unable to get an appointment, so he then went to the emergency department of the Morales Meseguer hospital in Murcia to ask for a prescription for a drug to treat schizophrenia. The bag he is seen carrying in the photo of his arrest by Spanish police at a cheap hotel in Murcia contains his medication.

"After he was released, he called me and I went to see him," says Ulpiano. "He was very upset about the media coverage of the case. He said he had not expected to be pardoned. He was more surprised than anybody else. He insisted that he had only asked to be allowed to serve the rest of his sentence in a Spanish jail. One of the last things he did before being arrested in Spain was to buy EL PAÍS: he wanted to give an interview and clear things up, he said."

At one point, there were rumors in the media, which EL PAÍS published, that Galván had worked for the Spanish intelligence services, the CNI, and that this was the reason he had been released. Both Rabat and the Spanish authorities have dismissed this as untrue.

"If he did work for the CNI, he managed to hide it very well. He laughed when he read that he was now being accused of being a spy. We joked about it, and he said that when they finally arrested him, he would tell the police officers that he had contacts in the secret service," says Ulpiano, who adds that Galván knew he would be arrested and made no attempt to hide: "Galván entered Spain like anybody else; he didn't try to keep it a secret. He was the first person who wanted the matter of his release cleared up. There was no question of him going on the run."

How was Galván able to keep his crimes secret and avoid detection for five years, between 2005 and 2010? Hamid Krairi, the lawyer who represented several of Galván's victims, blames a combination of poverty and ignorance, explaining that in much of Morocco, and particularly among poorer and less-well educated groups, rape and sexual abuse are taboo: nobody will speak about them.

The families of some of Galván's victims also came from a small, closed community called Zaaitrat, in the small town of Mograne, 36 kilometers north of Kenitra. The village is surrounded by corn fields and land where sheep and cattle graze. Most people still get around by carts pulled by mules or horses, says Said Jamlich, a volunteer for an NGO whose Arabic name means Bridges. The organization encourages, with limited success, boys to finish school rather than leaving early and working on their families' farms. "The families of the children who were raped would have preferred that none of this came out, because for them it means shame and dishonor," says Jamlich. "Others would have kept the offense a secret in return for a small amount of money - that's how poverty works."

About three kilometers west of Zaaitrat, down a dirt road that runs between fields, is the farm of the mother of one of Galván's victims. Along with other members of the family, among them several small children, she is trying to herd her cows grazing nearby. On August 6 she went to the Royal Palace in Rabat with other families of children abused by Galván, and met with King Mohammed VI. He expressed his "deep compassion for the suffering and terrible exploitation that their children had undergone, as well as for the pardoning of the individual, and for the psychological impact on them," according to a statement issued by the royal household, which includes photos of Mohammed consoling the mothers of the children. The mother in question says she is glad the king received them, but refuses to say how she or the other families felt when they learned that Galván had been pardoned. She has nothing to say about Galván being allowed to finish his sentence in Spain. Asked what the king said when he met her, she answers: "that's a secret between him and me."

After knocking at several doors at random in the block where Galván lived in Dior Chebbi, a woman comes bustling down the stairway, quickly covering her head and face with a towel. She is the only person who has agreed to talk about the response of her neighbors to the pardon. "It's a disgrace, a disgrace," she hisses, while pointing to a doorway to her right where one of the children abused by Galván lives, indicating the height of the victim with her hand. She then recovers her composure and says she, like everybody else in the block, is unhappy that Galván will be allowed to serve out his sentence in Spain. "They should have brought him here, they should have let him out in the streets around here. He wouldn't have lasted long."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.