“Half a million for that crook Kindelán”

Declassified documents show how London dished out dollars to Francoist officials Payments from UK government ensured Spanish neutrality in World War II

On June 4, 1940, the British ambassador to Madrid, Sir Samuel Hoare, sent an urgent encoded “personal” message to British Foreign Secretary Viscount Halifax. In it he revealed that there were signs Spain might soon abandon its neutral position and enter World War II on the side of the Nazis. The moment to act had arrived, he concluded, adding that he believed he had a safe way to access the best-placed ministers.

That method, revealed in one of over 400 documents recently declassified by Britain’s National Archives, was “to influence policy decisively and ensure Spain’s neutrality” by paying bribes for which he said he might “need up to 500,000 pounds.”

“I personally urge authority be granted without delay, and that if you have doubts, the prime minister be consulted,” Hoare pleaded. In the end the British spent 13.5 million US dollars (222 million dollars in today’s money, or 170 million euros) bribing Francoist officials to keep Spain out of the war. The payments were made via the Mallorcan banker Juan March and the recipients had no idea the money came from Winston Churchill’s government. The main problem was not finding candidates to receive the bribes, but whether March could get hold of the funds without arousing suspicion. The account set up in a Swiss bank in New York was blocked by the US Treasury for several months.

Ambassador Hoare received the green light directly from Churchill and Chancellor of the Exchequer Kingsley Wood. On June 9 Hoare confirmed in a telegram that negotiations were proceeding satisfactorily, but warned that a larger sum than the original estimate of half-a-million pounds would be needed. On June 14 the Foreign Office queried his request for a higher amount to be authorized, asking for details of the operation and warning the ambassador that if the bribes were rejected and Britain’s involvement was revealed, the consequences would do infinite damage.

Hoare’s response came the very next day. He said he was wary about sending any names, even in an encrypted message, stressing that London had to accept his word that the recipients of the funds were figures at the upper-most levels of government. “It may well be that Spain’s entry in the war will depend on our quick action. The situation is critical,” he warned. On June 21 the Foreign Office confirmed the funds had been deposited in the Geneva Swiss Bank in New York.

A report signed by Commander Furse on June 26 and addressed to Churchill and Wood summarized the operation from the point of view of the mission in Madrid. It said that the embassy believed Spain was on the verge of entering the war and only the adoption of this strategy could avoid it. In its view, Franco wished to stay neutral but was terrified of Germany. The pro-German Ramón Serrano Súñer, Spanish foreign minister and Franco’s brother-in-law, General Juan Yagüe, the head of the Air Ministry, and the rest of the Falange’s left wing were in favor of intervention, Furse said. The Falange right wing — the Carlists, businessmen, most of the army and farmers — preferred to remain neutral.

The report reveals that Hoare’s aim was to give the right wing what it needed to organize itself against Súñer’s clique. The resulting organization would be pro-Spain and anti-foreigner -— as anti-Italian as it was anti-British — but would not claim Gibraltar until after the war. March, who had previously acted as a double agent for the British and the Germans in World War I, took charge of contacting all the relevant ministers and military officers, but not out of love. Not only did he end up pocketing over five million dollars but, in the opinion of the British, also wanted Súñer’s policies to fail in order to recoup his investments and increase his own power.

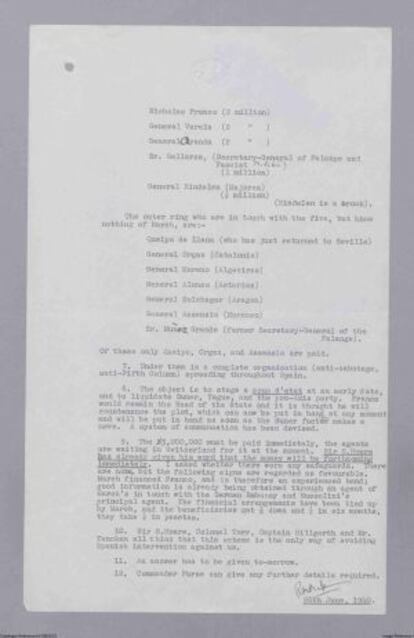

Furse’s document goes on to detail the payments and the degree of commitment of those involved in the operation, as well as the payment schedule. Later documents specify that of the 13.5 million dollars to be paid, 3.5 million would come at the end of the war. Of the other 10 million, two had already been paid when Furse sent his report, three had to be handed over immediately and the other five — March’s commission — after six months. The document lists those involved, headed by Franco’s elder brother Nicolás, and what each one was to receive in dollars: “Nicholas [sic] Franco (2 million); General Varela (2); General Aranda (2); Sr. Gallardo, (Secretary-General of Falange and Fascist Militia) (1 million); General Kindelán (Majorca) (1/2 million).” “Kindelán is a crook” it notes in parenthesis after the name of the founder of the Spanish Air Force.

Seven more figures were involved in the operation but only three, generals Gonzalo Queipo de Llano, Luis Orgaz Yoldi and José Asensio Torrado, received payments — though the amounts are not specified. The other four are generals Llana, Moreno, Alonso and Solchagar, and the former Falange secretary-general, Agustín Muñoz Grandes. On June 28, Ambassador Hoare sent a telegram to explain that the operation was bearing fruit. General Yagüe, the main driving force behind the move to push Spain into the war, had been dismissed, it said.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.