The Transition, frame by frame

National Library brings together the work of the cartoonists who chronicled the move to democracy

Peridis, the political cartoonist, stops to look at a comic strip he once drew about Spain’s first prime minister following the transition to democracy, Adolfo Suárez. On that day, Peridis had an intuition. His drawing, which was published in EL PAÍS on January 30, 1981, showed Suárez sliding down the column of power, pushed down by a large boot that morphed into a military cap, as he said: “You’re all kicking me out. God forbid you should come to miss me.” A few weeks later, there was a failed military coup that nearly toppled the fledgling democracy.

“It was a premonitory cartoon, an insinuation; nobody knew what the military was cooking up at the time, but I felt Suárez had done some great work and that we might miss him, which we later did,” says Peridis, the pen name of José María Pérez.

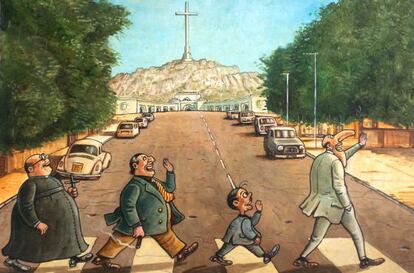

His cartoons and many others are part of a new exhibition at the Spanish National Library (BNE), La Transición en tinta china (or, The Transition in ink), that shows how the nation’s cartoonists were often ahead of the curve on many political and social issues during the transitional period following Franco’s death, in the late 1970s to the early 1980s.

For instance, there is a 1984 cartoon by Chumy Chúmez about the social protests over economic hardship — an eerily familiar theme to Spaniards today: “Nationality?” asks a severe-looking man from the superiority of his armchair.

The nation’s cartoonists were often ahead of the curve on many issues during the transition

“Poor,” is the simple reply.

There are also satirical takes on the sincerity of some of Spain’s newly minted democrats. “What people who criticize us Francoists-turned-democrats don’t know is that Franco, who left nothing to chance, had created a corps of secret democrats,” reads a strip by Martínmorales.

“When it comes to humor, the Transition began earlier,” notes the exhibition’s curator, Francisco Bobillo, a political scientist who sets the starting point for this transitional period at 1972 with the first issue of Hermano lobo, a satirical magazine modeled after France’s Charlie Hebdo, and ends it in 1986, when Spain became a member of NATO.

Choosing Hermano lobo (Brother wolf) is also a tribute to a publication that defined itself as “a humorous weekly inasmuch as is possible” — just reading the magazine was a sign of rebelliousness. Several writers and cartoonists who contributed content between 1972 and 1976 would go on to develop illustrious careers, including EL PAÍS cartoonists Forges and El Roto.

At times of great censorship cultural creators display their greatest creativity”

Political humor really took off as a successful industry in the 1970s, which also saw the launch of seminal magazines such as El Jueves, which is still published today, and Por favor, where El Perich published strips that captured the absurdity and contradictions of the system: “We are going to establish a dialogue,” reads one.

“All right, then.”

“No talking please, all you have to do is applaud.”

“These cartoonists made light of existing problems, but it doesn’t mean they were avoiding them,” says Bobillo about an exhibition that showcases the work of around 80 cartoonists and samples of 25 publications (half of which are now defunct). “Readers connected with them immediately, and they connected with the readers.”

Among all these male cartoonist was one feminist oasis represented by Núria Pompeia. In a strip dated April 1978, she recreated a dialogue between an elderly woman and her granddaughter: “And they were married and lived happily ever after and had lots and lots of kids.”

“Why didn’t they use contraceptives?”

Until Franco’s death, and even beyond, criticism of the regime used veiled language. “There was an intense use of euphemism, a secret metalanguage between authors and readers, which from today’s viewpoint, may not be well understood,” explains Forges, standing in front of one of his own cartoons that reads: “Apparently it’s imminent.”

“What is?”

In that straitlaced society smelling of mothballs, cartoonists opened up cracks of fresh air

“What else could it be?”

“You’re kidding!”

Nothing was stated in the text, but everything was there between the lines. Any reader who saw this cartoon on April 4, 1975 knew immediately that it was referring to the death of Franco, which rumor had it was imminent (in the end, the dictator died on November 20 of that year). “It is at times of great censorship that cultural creators display their greatest creativity,” says Forges. “You could say practically anything, as long as you used the right amount of brain cells.”

In that straitlaced society smelling of mothballs, cartoonists opened up cracks of fresh air. “We were allowed to live through tough times with a sense of humor,” said BNE director Ana Santos.

“Using either subtle irony, bold malice or brutal sarcasm, these cartoonists pushed the political process forward, even anticipating it at times,” writes the secretary of state for culture, José María Lassalle, in the show catalogue. “They were the entertaining heralds of liberty.”

One entire section of the exhibition is devoted to elections, an object of desire during any dictatorship. The cartoonist Sir Cámara published the following strip in the now defunct daily newspaper Diario 16: “You see? Here are the ballot boxes,” says Franco holding one in his hand.

“What about the ballots?”

“See what I mean? We give them an inch and they take a mile.”

La Transión en tinta china. Until August 25 at BNE, Paseo de Recoletos 20-22, Madrid. www.bne.es

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.