Cinema’s longest night

Ten years ago actors turned the Goya ceremony into a virulent anti-war protest Fears abound that Sunday’s gala may witness fresh controversy over PP cutbacks

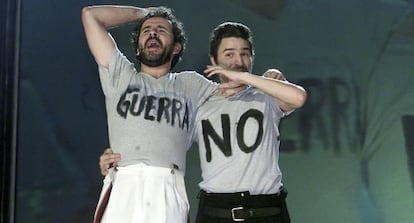

It’s been a decade since that fateful night when the Spanish film industry’s foundations were shaken to the point of altering relations within the sector, between the public and the industry, and between the industry and Spain’s politicians. The Goya Awards ceremony of 2003, remembered for the “No to war” signs protesting Spain’s participation in the Iraq conflict, triggered a bitter crisis that strained relations almost to the breaking point. Industry workers, spectators and politicians were divided over the fact that a professional body was using a privileged platform — live television coverage of the Goyas — to express its rejection for the policies of the conservative government of José María Aznar.

It has been a decade since those pins and buttons went on prominent display on actors’ lapels, yet the countdown to this Sunday’s award ceremony has been punctuated with the sounds of war drums once again. The great celebration of excellence in film could become another showcase for protests, slogans, placards and controversy over the new target of the industry’s ire: the government’s cultural spending cuts and its brutal hike of value-added tax, which has sent box-office ticket prices spiraling.

The Spanish film family has always veered notably more towards the political left than the right, and the fact that these changes have been introduced by the conservative Popular Party (in power now as then, in 2003) augurs a night of vocal protests. In fact, alarm bells have already gone off over what might transpire on Sunday. Even Enrique González Macho, president of the Spanish Film Academy, is openly worried following the decision by the actors’ guild Unión de Actores y Actrices and the TACEE audiovisual technicians union to encourage its members to protest the cuts “in their role as citizens.”

Everyone is free to comment but I disagree with using the Goyas this way”

“The ‘No to war’ gala was a mistake,” says González Macho, now admitting that the 2003 ceremony’s aggressive tone was not positive for the Spanish film industry’s image. The Academy leader says he is not in a position to make recommendations regarding what should be said on the stage, but he does issue the following warning: “Everyone is free to make whatever comments they consider opportune, but I disagree about using the Goyas to do so. This ceremony is an event in which Academy members recognize and honor the best performances from the previous year. To use this space is to invalidate a festive event,” he told this newspaper.

The Unión de Actores y Actrices on Monday reminded its nearly 3,000 members about their duties with regard to the Goya Awards, which will be aired live by the state broadcaster TVE (the advent of social media put an end to the infamous phony live coverage, which allowed for cuts). Referring to the fight against government cutbacks to public services, the union’s press release said: “We don’t know what teachers or doctors would say if they had two hours of live air time to celebrate and promote their professions — which would be a good thing, given the smear campaign they have suffered. We do know what they have been doing for months and years on the street: defending what belongs to us all.”

Alberto San Juan, one of the authors of this press release and a leading protester at the 2003 ceremony, denies any instigation to action. “We are not telling people what to do. It is simply an invitation to think. We need to take advantage of every circumstance because this is everyone’s fight. This is not a crisis, it is political and financial pillaging.”

Yet that famous No a la guerra ceremony was not the only controversial one. A year later, filmmaker Julio Medem was booed by a handful of people at the entrance of Madrid’s Convention Center for his documentary on the Basque Country, La pelota vasca, which angered ETA victims because they said it placed victims and murderers on the same footing.

We are not telling people what to do. It is simply an invitation to think"

The Goya ceremony has always been a desirable spot to vent one’s anger. A variety of groups have yelled out their slogans at the door, from Telefónica or TVE employees to members of the hacker group Anonymous, who lobbed eggs at the participants from behind their V for vendetta masks. This time, it’s not just the actors who are in the frontlines of confrontation. Last year, the only person to voice a complaint at the Goya Awards was Licio Marcos de Oliveira, winner of the Best Sound prize for No habrá paz para los malvados. The Brazilian sound expert was wearing a TACEE union pin on his lapel, and used his acceptance speech to underscore the precarious situation of most cinema workers. TACEE has organized a protest for Saturday morning which will be attended by six award nominees, including Paco Delgado, who is also in the running for a costume design Oscar for Les misérables.

TACEE coordinator and spokeswoman Gabriela Weller explains: “We did not consider the option of turning the awards ceremony into a demonstration, because our members see it as a party. But when the situation gets this serious, and not just for movie industry workers, freedom of expression must prevail, and everyone has the right to say or do whatever their conscience dictates.” Yet both TACEE and the actors’ guild insist that “there is no desire to bust the party.” Iñaki Guevara, secretary for Unión de Actores, insists: “Nobody should get scared. This is simply a call for reflection.”

“I am not a censor,” explains González Macho. “I will never tell anyone what they have to say, but everyone must know their place. Politics is to be exercised individually, not collectively.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.