Tuning up the movies made by Spain’s answer to Georges Méliès

New York composers have written new scores for films by Segundo de Chomón

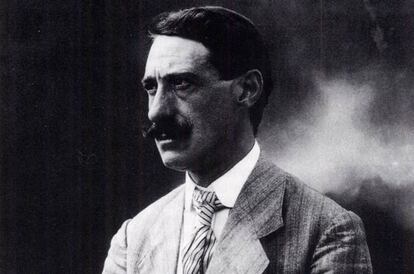

There was a time when cinema was not yet an art form, but rather a magic trick. Back then, when all films were silent, black-and-white and didn’t last more than a couple of minutes, the center of the movie world was Paris, where the big producer was Pathé. That was the home of Spaniard Segundo de Chomón, a filmmaker now venerated as a visionary and master of visual trickery.

The National Gallery of Art in Washington last week screened some of his short films with new soundtracks composed by members of the Steinhardt program at New York University, among them the Catalans Sergi Casanelles and Tomas Peire. The program forms part of a major retrospective of artist Joan Miró in the US, which the museum will host until August 12.

Among the most impressive of Chomón’s short films is El hotel eléctrico (or, The electric hotel) from 1908, which the gallery screened with Casanelles’ music. The film portrays a hotel with a life of its own: the suitcases unpack themselves; the brooms sweep on their own; beards are shaved without the help of a human hand. It is a creation up there with those of Chomón’s main competitor, the famed cinema pioneer Georges Méliès.

Like the French filmmaker, Chomón was a master of stop-motion animation, a technique used a great deal by the early film pioneers that consists of shooting a frame, stopping the camera and changing the position of the characters and objects before shooting another one. The result is a magical movie continuity trick, and one of the few ways of creating celluloid fantasies before the use of computer technology.

Chomón was born in Teruel in 1871. As a young man he moved to Paris where he studied the Lumière brothers’ pioneering techniques. He developed his knowledge in Barcelona until Pathé gave him a contract to return to France. As an answer to Méliès’ famous work A Trip to the Moon (1902), Chomón made his own A Trip to Jupiter (1909). In 1910 he returned to Barcelona where he carried on making films. His reputation was such that he was commissioned to create the special effects for Giovanni Pastrone’s Italian epic Cabiria (1914) and Abel Gance’s masterpiece Napoleon (1927).

For his score, 32-year-old Casanelles says he researched the historical context of the films. “We tried to give it a historical focus, with music characteristic of what was going on in the period,” he explains. “The idea was to maintain a narrative in keeping with the historical context, not to resort to contemporary compositions, but be inspired by the tastes of the age, such as French impressionist music or the Igor Stravinsky of the turn of that century.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.