From yesterday's excesses to a fear of tomorrow

With the budget ax poised to fall, anxiety is growing among Spain's publishing, cinema, theater, music and art sectors

Given the predilection of the people in this country for seeing things in black and white (extremism), and their dislike of gray areas (subtlety), the emergence of two opposing camps in the ring where the future of culture is being slugged out is not surprising.

The two sides are as blindly convinced of their arguments as they are incapable of holding them up against even the slightest intellectual scrutiny. In one corner is the 'Mama Spain' team, happy to milk eternally from the udders of the state. In the other, and equally as self-interested, is the talibanized team, spouting the timeworn mantra that "culture is a luxury."

The first group was so intent on its laborious mission of getting as much out of the state coffers as possible that it didn't even see the débâcle coming. Giving no thought to saving for a rainy day during the good times, and spending like there was no tomorrow, this team witnessed its own downfall (behavior that was not confined to the cultural arena).

And it goes without saying that tomorrow has definitely arrived.

The talibanized team, on the other hand, now has the situation of its dreams; it has the perfect excuse to ready its ink, images, radio waves, posts and tweets and take aim against the culture vultures, those whom it has perceived since time eternal as bleeding-heart liberals that automatically align themselves with social-democratic governments over neoliberal ones. One thing is clear (and the taliban team is partially right in this): if you have to choose between shutting down an operating theater or a baroque concert series, there's no contest. The problem arises when you shut down the concert series and then the operating theater too, as is now happening. These are times of grave economic crisis, of drastic cuts, and consequently, of both individual and social schizophrenia.

If nothing else, this means one thing: it is unlikely that things will ever go back to the way they were before. The way the Republic used to be run is done and dusted; new management models are called for, which is where those in charge of managing our cultural assets enter the picture. There is also the need for a giant collective leap of the imagination from which nobody - artists, administrators, politicians, businessmen or even the recipients of these cultural assets, the public - should be excluded.

Theaters will close and summer music tours will become a thing of the past

Though the state budget will be unveiled on March 30, by now there are few naïve enough to believe that the ax set to fall on culture (like looming cuts to many areas) won't make us shake in our shoes. It should also come as no surprise to anybody, least of all the minister of education, culture and sport, José Ignacio Wert, that from that point on, efforts to convince the Economy and Finance ministries that culture is a fundamental asset that must be protected and financially supported will be futile. With the best will in the world, it will be nearly impossible to persuade those in charge of the numbers in Spain that literature and art are also important - and not only operating theaters, factories, highways, air traffic controllers, farmers and apartment buildings.

The already weakened financial state of the cultural sector has revealed a stark picture of the scrape in which Spain's publishing, movie, theater, music and art worlds find themselves today. While the money flowed like champagne, it was spent carelessly with little thought for creating viable avenues for long-term revenue generation. Now these industries cannot even make ends meet and there is a desperate need to find new ways of running them.

It won't matter how many brilliant figures from the cultural world pound on the doors of officialdom; there is no money, and there won't be any, certainly not in the short and medium terms, and possibly not in the long term. Those who will feel the immediate effects are professionals in the cultural sector (these industries generate nearly 600,000 direct and indirect jobs in Spain, and constitute four percent of GDP), followed by spectators, readers and museum visitors.

The potential fallout of this social psychodrama is wide-ranging and varied: movie productions that are halted or never started; libraries that are closed or forced to make cuts in funding, staff and hours; dozens and dozens of theater companies (some of which have produced big-time successes) that find themselves unexpectedly debt-ridden and doomed to an uncertain future - if not outright closure - when the governments that hired them are unable to pay their bills; museums that have their doors open but interiors empty, and have no hope of organizing any new exhibitions; prestigious and recurrent classical and pop music cycles and festivals that are terminated (mainly because the companies that sponsor them are no longer able to do so); and trusty summer music tours that will soon become a thing of the past.

In a recent interview with EL PAÍS, the secretary of state for culture, José María Lassalle, let drop a statement that, upon second glance, was very worrying: "Our priority is to prevent the closure of museums and libraries." This is the man who is second in charge of the government's cultural management admitting that, although still distant, the threat of museums and libraries closing their doors is real. His words were undoubtedly meant to reassure, but in reality, had the opposite effect.

In the same interview, as expected, Lassalle made the inevitable mention of these "very difficult times for Spanish cinema." His conviction that a new model of management is needed was clear - one that is based on the already growing contribution of private companies to cultural funding. Though it is not stating this clearly, the Popular Party government aims to have private sponsorship take the place of subsidization. It remains to be seen if this culture of sponsorship (or sponsorship of culture) finds its perfect home in the much-touted but still mysterious Sponsorship Law that Wert and his team have proclaimed a godsend.

The "mixed model of subsidies and fiscal exemptions" remains a mystery

In this current episode of the search for private funding to ease culture's malaise, it would be a real scoop to find out how the minister plans to bring to fruition the "mixed model of subsidies and fiscal exemptions" meant to revive the flagging movie industry. The sector has witnessed a virtual collapse in activity in terms of the number of new productions: 21 in the first quarter of this year as opposed to the 58 launched over the same period in 2011.

Things are no rosier in the music world. In a video series for EL PAÍS, Enrique Subiela, who represents stars such as pianist Lang Lang, mezzo-soprano Cecilia Bartoli and reputed orchestra conductor Gustavo Dudamel, said that the "crazy method used to hire performers and orchestras has led to the collapse of the system; it is destroying us."

And things are even worse in the world of pop music. The collapse of live music is now following that of the record industry. The debt of municipal governments to members of ARTE (the Association of Performance Technicians) now exceeds 70 million euros. You can say goodbye to summer gigs... and festivals and concerts - and even musical entertainment during town festivals. Where town-hall organizers used to have an average budget of 200,000 euros to spend on their week-long festival, today these do not exceed 30,000 euros (granted, this is a situation that has been in the works since 2009).

In a country where the educational system has always failed to instill a sense of passion for culture in its youth (as opposed to France, for example) and where politicians and administrators have never given too much thought to searching for funding alternatives in the private sector (as is done in the UK), the slow death of certain forms of expression and the infrastructure behind what might be called our spiritual assets is, though sad, no more than just deserts, brought on by a stunning lack of ambition and vision.

Finding a DIY solution to cultural cuts

They consider themselves the offspring of the crisis because the model of opulence has proven itself unviable. And, in general, they are the siblings of citizen-backed movements such as 15-M. Madrid's Tabacalera, Málaga's Casa Invisible, Granada's TRN and Barcelona's Hangar are testament to the fact that the end of the subsidy culture does not need to paralyze cultural activity. Concepts such as time banks and information exchange are their most valuable assets and with them they manage to ensure that artists have the necessary means to carry out their projects.

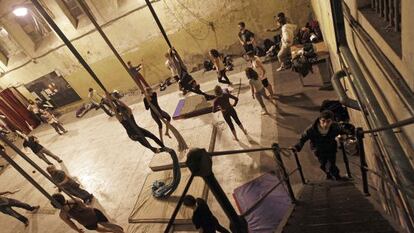

A few years ago, Madrid Tabacalera Self-Managed Social Center, located in a former tobacco factory in the central neighborhood of Lavapiés, was a reference for other like-minded initiatives. Following a brief period of closure due to institutional battles, the center has been in full operation since February of 2010 when the Culture Ministry granted it use of the building's ground floor (which covers more than 9,000 square meters) in a two-year renewable agreement.

The Ministry pays for electricity, water and security. All other activities are carried out by the center's users, which to date have included the restoration of the building's splendid halls, the provision of computers, the holding of classes and rehearsals that have made movie and theater productions possible, and the publishing of books (through the center's own Papel de Fumar publishing house).

Mariví Sonte (a pseudonym used by every spokesperson there) explains that anybody who has something to contribute and understands that the group does not serve individual interests can participate in the center. The latter is the only non-negotiable condition.

Backed by a multicultural and multiethnic group of residents, the daily agenda is displayed on a large blackboard located in the building's main entrance. There, one can read that today's Chinese language classes will be followed by a drama workshop or a meeting of victims of the Franco regime.

Málaga's Casa Invisible, which has been operating for five years, is located in a sprawling complex in the middle of the city. The product of a squatters' initiative, the group signed an operation protocol with the city, provincial and regional authorities a year ago. It's an agreement it hopes to expand to a five-year term.

Aiming to promote citizen-based management and to offer the social and cultural activities not provided by public bodies, the center's users number in the hundreds.

Nico is a familiar face at meetings there. He explains that there are three key areas of activity: participation, training and experimentation. The latter includes all types of musical performances, plastic arts and even history seminars. And an increasing number of people are participating. Nico does not have any doubt that this model is sustainable, mainly due to the fact that it serves no other interests apart from those of citizens.

The social and artistic groups behind this new cultural model have found an ally in the internet that allows them to publicize their activities beyond the stages and four walls where they perform and work. They do not aspire to replicate conventional set-ups, the kind of model now in its death throes in Spain as a result of public spending cuts.

"This model is more closely aligned with the approach of the 1980s, when the only thing that mattered was the pursuit of wealth and fame. These are different times," Mariví Sonte explains.

In general, inter-center relations remain within their own circles. But there are others promoting this new model who may be thought of as traditional players, including small museums such as Granada's José Guerrero, which operates on a modest scale and does not boast grand ambitions.

Yolanda Romera, the museum's director, contradicts the current tide of pessimism: "Small initiatives were also developed during the economic boom, and they are more likely to survive this cultural ice age. It's important to remind people that there were some acts of good sense during the years of boom and waste.

"Probably the lack of proportion of the centers and museums in relation to the size of the cities they were placed in is at the origin of the current tragedy. I don't think it's good to spread the idea that there are too many museums or art centers in our country. Is a medium-sized city incapable of having a dynamic museum that is local but not parochial and managed by a small team of professionals who work with a network of other institutions?"

Romero shares the opinion that the new management models could provide the boost the sector needs. She lists examples such as Málaga's Casa Invisible, the artist-run TRN project in Granada, and the Tabacalera, Noestudio and Off Limits in Madrid.

"There are many more. Coming up with ideas is not going to be a problem," she says.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.