‘Failing over and over again’: How James Dyson’s coveted vacuum cleaners made him the UK’s richest man

By embracing failure, the engineer and industrial designer has revolutionized domestic life with radical inventions

Meeting one of the richest men on the planet is a rare opportunity. Sir James Dyson, a Knight of the Order of the British Empire, has a net worth of around €25 billion (nearly $26.7 billion), which puts him near the top of the world’s wealth rankings compiled by the likes of Bloomberg and Forbes. But Dyson’s wealth came from creative and industrial pursuits, not financial speculation and sleight of hand.

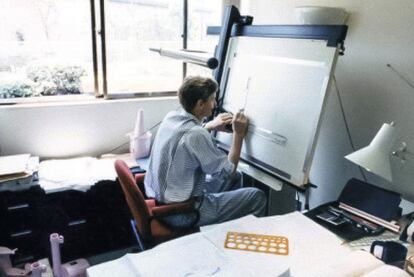

Dyson is both an engineer and inventor by nature. From an early age, he recalls delving into the inner workings of various objects, seeking to unravel their mysteries. Among his many interests, motorcycles captivated him the most, as they epitomized pure engineering without the ostentation of cars that often prioritized form over function. This notion, that exceptional design embodies elegant functionality, remains a guiding principle of his work.

Dyson says he made his fortune by “failing over and over again.” What he referred to as failures were actually unsuccessful attempts that provided valuable learning experiences to keep persevering. In the case of his groundbreaking invention — the G-Force bagless cyclonic vacuum cleaner — he went through 5,127 prototypes over four intense years. Despite facing a boycott from many British retailers who were reluctant to give up sales of vacuum bags, the G-Force was successfully launched in 1986. Its first triumph was in Japan, a country known for early adoption of innovative products, and it soon gained popularity worldwide.

Today, Dyson vacuum cleaners feature a futuristic design, a hygienic emptying system and a $300 price tag. They still sell very well and had a transformative impact as the 20th century waned, according to industrial designer William Welch. James Dyson went on to develop an extensive range of products: washing machines, hand dryers, hair dryers, fans, air purifiers, headphones and even a prototype of an electric car that “will never see the light of day,” said Dyson. “Although it was a technically impeccable design, we knew it would never be competitive.”

Dyson believes that perseverance is his most important quality, even more so than inventiveness. He never gave up, even when everything seemed to be falling apart. A group of journalists was invited to meet Sir James at a royal estate in the Parisian neighborhood of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, on the banks of the Seine. We walk quietly across beautiful patios and rooms until we reach the large study where Dyson, wearing a gray turtleneck sweater, awaits us on an exquisite modular sofa next to an electric fireplace. He wants to talk about his new book, Invention: A Life of Learning Through Failure, a chronicle of a life dedicated to failing.

Dyson discusses his studies in furniture and interior design at the Royal College of Art from 1966 to 1970. He describes it as a chance to immerse himself in the vibrancy of London, experiencing the excitement of early Pink Floyd concerts and the colorful Carnaby Street fashion scene. He says painter David Hockney was a significant intellectual and aesthetic influence. “I was training for a profession — design — which didn’t even have a name back then, even though we had excellent examples like the Bauhaus movement. Hockney, the most brilliant contemporary artist we had at our school, taught me something valuable. Besides being very talented, he was always researching new things. He showed me that art and industrial design are basically all about creativity, and you can’t separate functionality from beauty.”

Dyson takes pride in having many of his creations showcased in museums. The DC02 vacuum cleaner has been part of the Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) permanent collection in New York since 1994, while the G-Force was one of 12 objects selected for a charity exhibition at the London Design Museum in 2016. These accolades from the art world confirmed the designer’s intuition that useful objects can also be beautiful.

Reflecting on his career, Dyson comes to some paradoxical conclusions. “Experience doesn’t really hold much value because we can’t rely on the past to help us solve the problems of today.” The key is to keep failing and taking gradual steps closer to success. “I still go to the studio every morning seeking talented, young individuals who bring fresh ideas without preconceptions. I’ve tried to remain creatively objective by not involving financial and marketing departments in design decisions. They know I’ll bring them a finished product from the lab and ask for help selling it.”

Dyson’s approach admittedly involves challenging setbacks, such as the 2019 cancellation of a project to make an electric car that would compete with Tesla. “I brought together over 500 people to work on an effective prototype. However, we saw that big companies were willing to sell at a loss to gain market share, which we couldn’t afford. So I had to cancel the project. It was a tough decision, but the technological learnings can be applied to other projects, and most of the talent we recruited stayed with the company.”

Failure is fertile, Dyson tells us repeatedly. It fuels innovation, which “is the only thing that really matters.” One of his efforts is focused on sustainability, recognizing energy conservation as a significant modern challenge. Dyson is involved in other projects like his organic farms and the Dyson Foundation, which he manages with his wife, painter Deirdre Hindmarsh. The inventor describes himself as a passionate professional who is constantly engaged in his work. “If there is one thing I’m not, it’s a businessman. Write that down, because I want to be clear about that.” Hockney followers like Sir James Dyson seem to have mastered the art of failing their way to financial success.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.