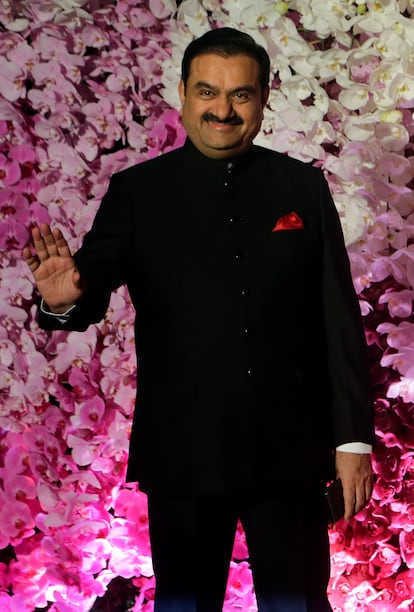

How the ‘king of coal’ became the third-richest man in the world

The energy crisis has lifted Indian businessman Gautam Adani, who survived the Mumbai terrorist attack, to the podium of the global rich list with an estimated fortune of $125 billion

In 2022, Indian businessman Gautam Adani has risen 12 places on the list of the richest people on the planet, according to Bloomberg. The 60-year-old now occupies third position, behind only Elon Musk and Bernard Arnault, with an estimated fortune of $125 billion. Over the course of this year, when the world’s largest fortunes have been hit by stock market dips, Adani has added $49 billion to his bank account. The misfortune of others has been a blessing for the Indian entrepreneur, who has hit the jackpot with two key industries: maritime transport and mining. Bottlenecks in the global supply chain have strangled worldwide commerce for several months and he is the largest operator of ports in India. He is also one of the biggest extractors of coal in the world, at a time when the energy crisis sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has given fossil fuels renewed luster on the global markets.

Being in the right place at the right time. Adani’s life has been marked by providential good fortune: few people survive both a kidnapping and a terrorist massacre. Born into a middle-class family dedicated to the textile trade, Adani abandoned his studies at an early age. He tried his luck as a diamond merchant and in 1988 he founded a commodity trading firm, the seed of his current empire.

His rapid social rise did not go unnoticed, and in 1995 he was kidnapped outside a club. Although he was released shortly afterward, local press reported that his freedom came at a price: $1.5 million. It would not be the last time Adani’s life was in danger. Years later, on November 26, 2008, he was lunching with friends at the Taj Mahal hotel in Mumbai when it was attacked by terrorists. Adani was unharmed after managing to hide in the basement of the building with the help of hotel staff until Indian commandos stormed the building. “I saw death at a distance of just five meters,” he told reporters after the siege.

Career parallels with Narendra Modi

Another stroke of fate concerns his birthplace, Gujarat, where Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was also raised. The growth of Adani’s business empire has strong parallels with Modi’s political rise. He started his maritime enterprise in 1995 when he won the tender to manage the modest port of Mundra. A few years later, in 2001, Modi was elected governor of Gujarat for the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party. Within months of his victory, more than 1,000 Muslims were killed in his jurisdiction and Modi was accused of doing nothing to curb sectarian violence. Adani came to his defense and proposed a business summit to promote investment in his home region. “Adani and Modi enjoyed at least a marriage of convenience: the mega-project obsessed politician and the ambitious young industrialist, both gradually becoming indispensable to one another,” writes James Crabtree in his book The Billionaire Raj.

Today, the Adani Group is a giant whose interests extend from coal and ports to infrastructure and real estate. The stock market value of its listed subsidiaries exceeds $200 billion. The Indian tycoon’s roadmap is the diversification of his empire, both in terms of businesses and geographic origin. Last May, he bought the Indian cement subsidiary of the Swiss group Holcim for $10.5 billion. He is also closing in on becoming the majority shareholder of NDTV after launching a hostile takeover bid for the television broadcaster - one of the most critical voices toward the Modi administration.

Adani’s dream, though, is to become the messiah of renewable energy: quite the contradiction when taking into account that his companies’ mining operations generate more than 3% of all carbon dioxide emissions from coal use in the world, according to advocacy group SumOfUs, as cited by Bloomberg. He presented his ambitious energy plan on September 27 during a speech at the Forbes Global CEO Conference held in Singapore. “As a group, we will invest over $100 billion of capital in the next decade. We have earmarked 70% of this investment for the energy transition space. We are already the world’s largest solar player, and we intend to do far more,” he announced.

The enormous investment effort promised by Adani – whose holding company is beginning to accrue a notable level of indebtedness – is also a key element in the plans of the Modi government to counteract China’s growing influence in the Indian Ocean through its New Silk Road program. This conjunction of interests includes, for example, the construction of a new port in Sri Lanka by Adani’s conglomerate. At the Singapore conference, Adani elected not to reproach Russia for its invasion of Ukraine but instead eschewed sibylline business diplomacy to give Beijing a good kick in the teeth: “China will feel increasingly isolated [..]. Increasing Nationalism, supply chain risk mitigation, and technology restrictions will have an impact. China’s Belt and Road initiative was expected to be a demonstration of its global ambitions, but the resistance now makes it challenging. And its housing and credit risks are drawing comparisons with what happened to the Japanese economy during the ‘lost decade’ of the 1990s,” he predicted.

A few years ago, Adani offered to act as a sponsor to the London Science Museum. The museum, concerned about the reputation of his companies as polluters, commissioned a report from an NGO that concluded the Adani Group was at the bottom of the environmental league table, second only to Saudi Aramco and Exxon. Despite this, the museum decided to look the other way. In October 2021, it inaugurated a new space that was baptized “The Adani Green Energy Gallery.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.