‘The Name on the Wall’: Nazis must be taken seriously

Hervé Le Tellier revisits the life and death of André Chaix, a young man who joined the French Resistance and died in 1944 at the age of 20, to lament the survival of fascism

A few years ago, sometime during the harrowing year of 2020 that would change everything, author Hervé Le Tellier discovered that someone had written a name on the outer wall of his new house in the village of La Paillette, in southern France. When he later found that the same name appeared on the monument to the town’s sons “who died for the homeland,” Le Tellier realized he had a story in his hands — and that he wanted nothing more than to tell it.

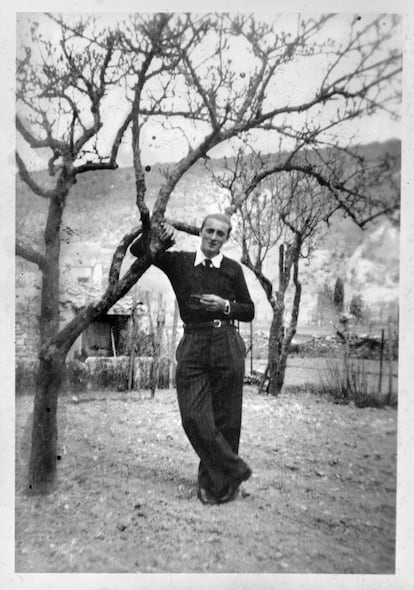

That story is about André Chaix, a young industrial apprentice from La Paillette who joined the French Resistance, fought in La Drôme, and died there in a German attack on August 23, 1944, at the age of 20 years, two months, and 30 days. To recount it, Le Tellier — a writer, mathematician, and literary critic, as well as editor of Raymond Queneau and Georges Perec and a member of the extraordinary literary experimentation workshop known as Oulipo — drew on photographs, documents from the archives of the National Association of Former Combatants, specialized literature on the Resistance in La Drôme, and testimonies from Chaix’s relatives who still live in the area. He also used a reasonable degree of speculation, but, as he says, it “would have felt obscene to invent anything.”

The Name on the Wall tells, therefore, a true story, and its purpose is to recount it as accurately as possible, as well as to express a visceral — yet ultimately common — discontent and irritation with the current state of affairs. “Seeing how the world is going, I have no doubt that we must continue to speak of the Occupation, of collaboration and fascism, of racism and the rejection of the other to the point of annihilation,” he says. “That is why I did not want this book to shy away from the monster against which André Chaix fought, why I chose to give voice to the ideals for which he died, and why I questioned our deepest nature, that desire to belong to something larger than ourselves that leads to both the best and the worst.”

Digressive and disconcertingly light, didactic, and unassailable in its critique of past and present complicity with fascism and hatred of the other, Le Tellier is at his best when he recounts his protagonist’s life. But that life was brief and books are long, and The Name on the Wall — along with its author — soon wanders into lengthy reflections on Germany’s responsibility for Nazi crimes; the postwar “denazification” that was deliberately mishandled in both Germany and France; the continuities between French collaborationism and the far-right National Rally party of Jean‑Marie and Marine Le Pen; The Third Wave sociological experiments on obedience; the performing arts in Paris during the Occupation; the solidarity and disobedience of the inhabitants of Dieulefit during the war; the history of the German 11th Panzer Division, and so on.

Nothing in The Name on the Wall feels out of place, although — as with The Anomaly, the book that catapulted Le Tellier to stardom in 2021 — one wonders how someone who belongs to a literary experimentation group can settle for such an unadventurous style. One also wonders whether this is a book conceived for classroom use: all its ideas are good, but you’ve read them many times before, and often better expressed by others. In fact, the author’s conclusions — “We must take Nazis seriously, and their delusions too,” “Life, like black‑and‑white films, is full of gray,” “Fate is a huge joke, not to say a scam,” and so on — and their lack of substance end up overshadowing, paradoxically, what is also a tribute to the handful of men and women who saved humanity.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.