Stellan Skarsgård: ‘Don’t try to be perfect. Tell your children: I’m sorry, I’m a piece of crap, but I love you’

At 74, the Swedish actor is one of the greats. And this year, he can finally dream of an Oscar, thanks to his latest film, ‘Sentimental Value’

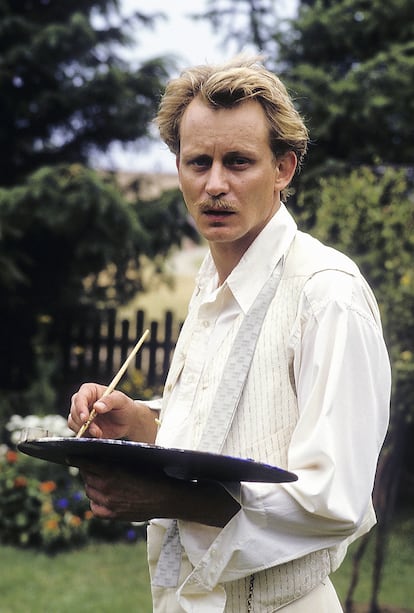

Stellan Skarsgård, 74, arrives early at his room in the Hotel María Cristina, during the San Sebastián Film Festival. The Basque city is a stop on the intensive international tour that began at the Cannes Film Festival to present Sentimental Value (2025), the latest film by Norwegian director Joachim Trier. Trier rose to fame in 2021 with his anti-romantic comedy, The Worst Person in the World.

Sentimental Value is a drama about the relationship between a father, Gustav — a renowned film director whose career has declined — and his daughters. If Bergmanesque influences were already visible in Trier’s previous film, in this one, they are even more blatant. After many years of absence, the father (Skarsgård) returns to the family home after the death of his ex-wife. He intends to reconcile with his daughters and film a screenplay he has written. He wants to cast his youngest (played by Renate Reinsve), an actress, in the lead role. But she, still angry at him, refuses. And so, he turns to a younger star, played by Elle Fanning.

What follows — for two wonderful hours — is a series of conversations and glimpses of the house that they once shared. There are reflections on family, life, death, what we leave behind and what remains. This melodrama has earned Skarsgård, who was born in Gothenburg, Sweden, his first Oscar nomination after six decades in the business.

When he meets with EL PAÍS, he’s tired. Three years ago, he suffered a stroke that has affected his work. However, he’s happy about the accolades for Sentimental Value… and also because his eighth grandchild has just been born. A self-proclaimed nepo daddy, the Swede is the father of eight children, six of whom are actors, including Alexander — from True Blood (2008-2014) — and Bill, from It (2017).

Question. Joachim Trier created this narcissistic father and director with you in mind.

Answer. [Laughs] I already wanted to work with him, because I’d been watching his films for a while. When he called me, I was ready to say “yes” without even reading [the script], but I held back and took my time replying. It’s such a delightful, beautiful and playful script…

Q. How close did you feel to your character?

A. I’m luckier than him because, even though we’re the same age, he’s from a different generation. And that makes it harder for him to deal with his feelings. Although, through art, he does it wonderfully.

In my case, since leaving the Royal Dramatic Theatre in 1989, I’ve only worked four months a year and have left eight free for my children. So, [the character and I are] very different, even though I understand the core of the conflict. Even though you’re a father — and precisely because you are — you have to work.

Q. There’s an eternal struggle between being a person, an artist, a father, a husband, a friend…

A. That’s life. I think the secret [lies in] not trying to be perfect. Tell your children, “I’m sorry, I’m a piece of crap, but I love you.”

Q. Perhaps your approach to work is what encouraged your children to follow in your footsteps.

A. Yes, they saw that I had a great time, that I was happy acting. And they wanted to try it. Alexander did a series when he was only 13 years old… he became so famous that he didn’t want to continue and didn’t do anything [related to the industry] for 10 years, until he got back into it.

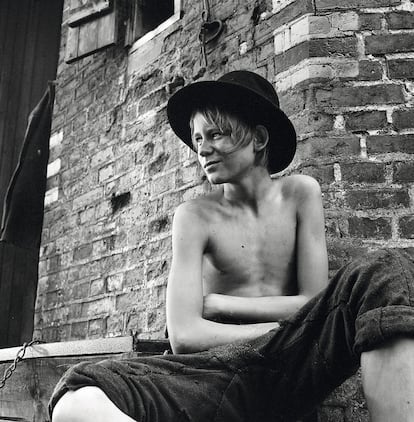

Q. And have you always been happy? Six decades in the business is a long time.

A. I’ve been through it all. For five years, I was terrified of the camera. I couldn’t [act]. It was awful. Until I participated in a small student film: it was so relaxed that I rediscovered my passion. But the fear is always there, lurking. That’s why it’s so important for me to create an atmosphere of trust and love on set.

Q. You’ve managed to stay current. From your early work in Sweden, with Ingmar Bergman and Von Trier, to Good Will Hunting, Mamma Mia!, Pirates of the Caribbean, Dune and Andor.

A. Staying current is the essence of my work. I play human beings… and there are still human beings among us today!

If anything worries me [about humanity], it’s that children can’t maintain their attention for more than five minutes. And the economic situation: [the fact that] a few people in the world control all the power and all the money… it’s terrible. And it’s getting worse all the time.

Q. So, are you a little nostalgic?

A. No, I’m not. What I do believe is that you can protest. Even Sentimental Value is a form of protest. We shot it on film, for goodness sake! And, in a way, it’s a defense of humanity, of the little things. There are no good guys or bad guys; they’re people full of nuances, contradictions, and surprises.

Q. The film is about reconciliation. Do you believe, like Joachim Trier, that “tenderness is the new punk”?

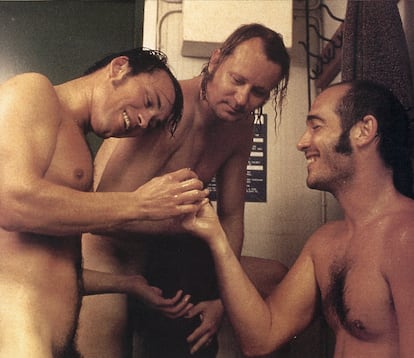

A. Yes, I do. It’s revolutionary. Perhaps it’s more so for Joachim, who comes from the generation of irony, because I come from the hippie generation and we were already soft and strange [laughs]. So, I haven’t had to learn about tenderness. But I do believe it’s essential to keep it alive and active, something that’s very difficult today.

Q. Do you think art can have an impact on this increasingly dehumanized world?

A. I don’t know, but I believe that art is important because it allows you to see the world through someone else’s eyes. What language can’t explain, art can.

Q. As human beings, if there’s one thing that defines us, it’s the concept of home, a house. In Sentimental Value, this is very literal: the house is the protagonist.

A. During filming, we always said that it was the most important actress (the one seen in the film belongs to the Norwegian rocker Lars Lilo-Stenberg); then, it was the rest of us. It’s a place that leaves a mark, [a structure] that’s filled with the ghosts of the past and the future. It’s such a delicate, fun and beautiful way of portraying time and the marks that history leaves on you. And how they’re passed down from generation to generation. It’s a visual image of time. The house doesn’t care if you live or die.

Q. Do you have a place like that, a place where the ghosts of the past and the future walk?

A. Yes, we have a summer house that my great-grandfather built on an island. It has electricity, but no running water or bathrooms; it has an outhouse. I spent many summers of my childhood there. But personally, I think you become less and less attached to physical memories as you get older. As a child, you tend to cling to everything because you’re very conservative and don’t want anything to change. And, in that sense, you’re more insecure. When you get old, you say, “Okay, I can let it go now.”

I also don’t believe in the idea of a house as absolute possession. I belong to my family… [and] we don’t live in that house. We all live — my children, all of us — in the same area of Stockholm, so we see each other every day, all the time.

Q. You never moved to the U.S., nor have you ever wanted to.

A. No, I’m happier with my children around me and with my grandchildren. Being a grandfather is more relaxing, although I think I was always a bit of a grandfather to my children, because I wasn’t very ambitious when it came to them.

Q. Is it true that you tried to be a diplomat before becoming an actor?

A. Yes, that’s what I wanted to do. Sweden had a secretary-general of the United Nations in the 1960s. His name was Dag Hammarskjöld. He dedicated himself to traveling and promoting peace. I wanted to be like him. But I started working in the theater and I enjoyed it more and more… and [the idea of] being a diplomat became less and less fun. And, as we were just saying, perhaps art can also bring peace.

Q. Do you see yourself acting for the rest of your life?

A. Well, for as long as I can… I can no longer remember my lines because I had a stroke three years ago, between Andor and Dune: Part 2. [Today], I wear a small earpiece and they whisper my lines to me. I can still work. Although, of course, sooner or later, you lose your mind…

Q. Are you worried about your legacy?

A. No, I don’t want to leave a legacy behind. I don’t even want to write my memoirs. Your family is your legacy; that’s what you leave behind. I want to die when I die. It’ll be fine.

Q. Sentimental Value will be one of the films that you’re remembered for…

A. We did so many versions of some scenes… Joachim could have ended up with a lousy performance, but he got a good one in the end [laughs]. I know [that my role] will be remembered, because it’s one of the best characters of my career.

Q. How are you handling the Oscar buzz at this point?

A. You can’t care because it’s idiotic to compete in art. But then you win and… yes! You’re happy. We’re only human beings, aren’t we?

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.