Art Deco at 100: The style that thrived, died, and came back with million-dollar auctions

The movement was born during the groundbreaking Paris Exhibition of 1925 as a luxurious response to the success of the German Bauhaus. One hundred years later, its prices keep breaking records

The finest hotels in Paris, the homes of today’s illustrious interior designers and the shopping lists of the most discerning antique collectors all have one thing in common: a craze for Art Deco.

This luxuriously geometric and eternally modern style (think of imposing black lacquer screens or expensive beige armchairs) recently turned 100-year-old. And, of course, it was born from the ashes of its opposing style.

In the 1920s, France viewed its ornate Art Nouveau chairs and lamps with concern. Admired until recently in the country’s most elegant salons, they had become proof of a national failure. While the Cubist paintings of Picasso and Braque, the rectilinear dresses of Chanel and the essays of André Breton kept the French at the crest of the avant-garde, modernist furniture and buildings had lagged far behind those of other countries, specifically Germany, which was under the influence of the Bauhaus approach to design.

Lucien Dior — the famous couturier’s great-uncle and then-minister of Commerce and Industry — took the matter very seriously. He spoke of the urgent need for French taste to (once again) prevail in the world of design. After arduous negotiations, he secured several hectares in the city center from the Paris municipality. This was just enough land to stage the mother of all applied arts exhibitions. From then on, the world would again be in need of the French “r” sound to describe the most sophisticated interiors.

“One trigger for France’s jealousy was the invitation that was extended to the Germans of the Werkbund [the design group that was a precursor to the Bauhaus] to the Salon d’Automne held in Paris in 1910,” Anne Monier Vanryb explains. She’s the curator of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (the Museum of Decorative Arts), in Paris. “The French felt so threatened by [the Germans’] furniture that they asked for their own exhibition, to help them win the commercial and cultural battle. It was supposed to be held in 1915… but then the [first world] war began.”

Considered the birthplace of Art Deco, the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industries Modernes — translated as the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts — opened on April 25, 1925. And, over the next six months, it attracted some 16 million visitors to the 15,000 pavilions that France, Spain, Japan, Austria, the United Kingdom, China and the rest of the invited countries (German designers weren’t invited this time) set up along both banks of the Seine, in the area between the Grand Palais and the Esplanade des Invalides.

According to the rules, participants were required to limit themselves to showing designs that were original and reflected clear modern tendencies. Not everyone understood it in the same way: some British visitors described Mussolini’s Italy pavilion as “a monumental horror of illiterate classicism with marble columns and gilded brickwork that would have disgraced Caligula.”

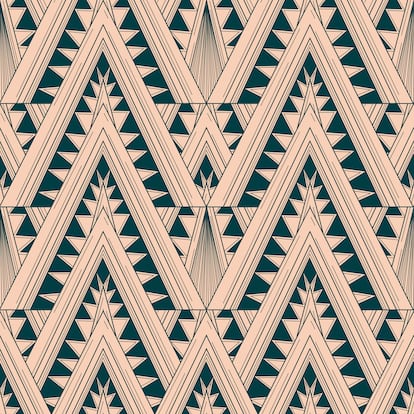

However, the organizers’ idea of modernism was clear even before entering the enclosure: designed by Louis-Hippolyte Boileau, a huge banner hung from the Porte d’Orsay (the most imposing of the 12 gates that were commissioned) on which ceramics, sculpture, architecture and furniture were represented by taut and elegant lines so characteristic of what — many years later — would be called the “Art Deco style.”

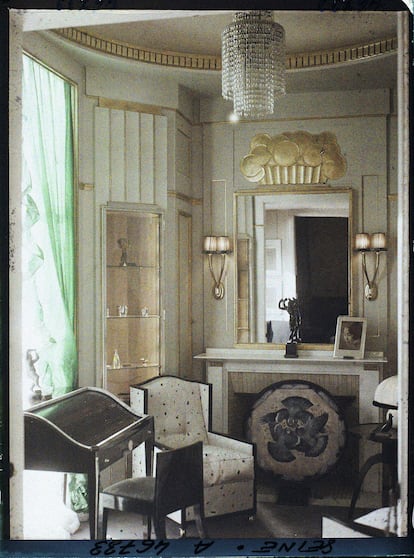

Strictly speaking, it wasn’t a new style. Before World War I, many artisans had already transferred the same angular shapes with which the Cubists had revolutionized painting to their pieces. They drew inspiration from African masks or Chinese and Japanese crafts, bending the sinuous curves of Art Nouveau. However, the 1925 Paris Exhibition added a very important ingredient to all these pieces: a veneer of glamor, without which Deco wouldn’t be the same. Thanks to this elegance, for many years, it remained the preferred style of ocean liners, luxury hotels and Hollywood films.

The exhibition’s location — next to some of Paris’s most beautiful views — was very helpful. And, above all, a close relationship was established between the worlds of design and fashion. This occurred via the participation of luxury department stores, such as Le Bon Marché and Galéries Lafayette — both present at the exhibition with their own pavilions — and Paul Poiret, the great French couturier, who chartered three barges on the Seine decorated in the Art Deco style to showcase his dresses and perfumes.

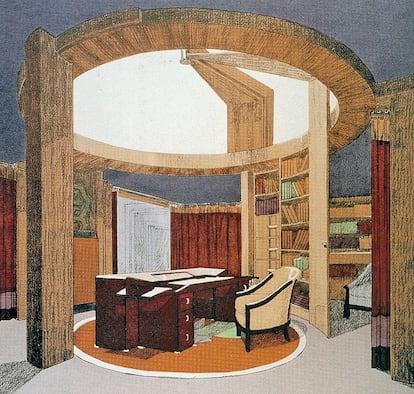

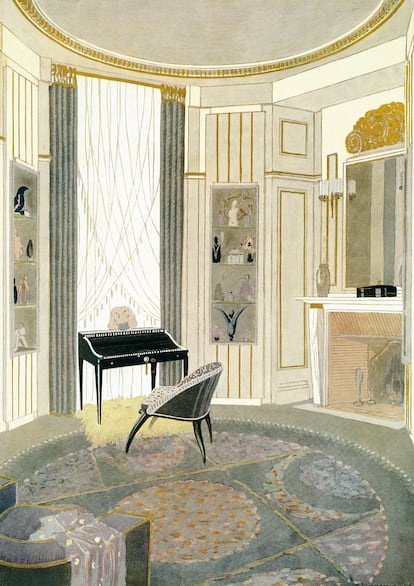

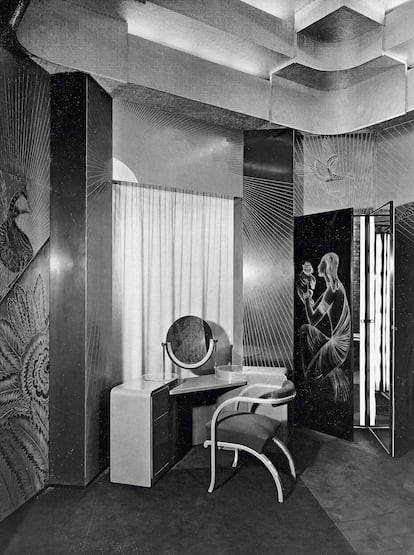

It was, to put it mildly, as if Chanel, Hermés and Jonathan Anderson had agreed to sponsor a specific decorative style: only the most exquisite options were valid. Rapin porcelain, lacquered panels (with which Jean Dunand transformed the French Embassy pavilion into a forest of geometric palm trees), Jean Lurçat’s carpets with Cubist designs, René Lalique’s gigantic fountain illuminated at night in the Esplanade de Invalides… and the most acclaimed pavilion of all, the Hôtel d’un Collectionneur. This mansion — designed by Pierre Patou for an imaginary collector — displayed the furniture of Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, the cabinetmaker in whom modern France finally found a Jean-Henri Riesener (the favorite of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette) for the new century.

Of course, the main attractions were the pavilions and exhibitors of French designers, strategically located in areas with the most spectacular views and far outnumbering those of foreign designers. After the exhibition closed in October 1925, no distinctions were made and all of them were demolished… but just as Christian Dior’s uncle had hoped, the goal of restoring French taste to the forefront was achieved.

In the following years, international exhibitions — such as the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair — used the Paris Exhibition as a model. This — along with the construction of Art Deco buildings in French colonies and protectorates, such as those in Casablanca and Hanoi, or in countries like the United States, which had sent delegations to visit the exhibition — led to the style spreading to every corner of the globe. Art Deco reached Tunisia, New York, Calcutta and, particularly, Shanghai, “the Paris of the East.” In this megacity, just a few months ago, Cartier sponsored an exhibition about the influence of traditional Chinese craftsmanship on Art Deco, which, in turn, influenced many Chinese designers.

As is often the case, the enormous popularity of Art Deco also marked its decline. It reached a point where even remote villages had their movie theaters decorated in this style. However, the most refined pieces retained the gleam that they had acquired in Paris. Half-a-century after the exhibition, furniture that was displayed in 1925 aroused the coveted attention of a new generation of collectors: from Andy Warhol — who conducted his Factory business on a Ruhlmann table — to Karl Lagerfeld, owner of several Dunand vases, among many other pieces. The German designer began to collect Art Deco in the early 1970s, becoming one of the first to bring the style back into fashion.

“Since the boom of the 1970s and 1980s, Art Deco has been unparalleled in the design market,” explains Adriana Berenson, director of DeLorenzo Gallery in New York City. Since its opening in 1981, the gallery has continued to break its sale records. For instance, it sold what’s considered to be one of the greatest Art Deco treasures: the Ruhlmann sideboard with a donkey and a hedgehog. Drawn in silver inlay, it presided over the great hall of the Hôtel d’un Collectionneur.

“The pieces from the 1925 Exhibition are the most sought-after and difficult to obtain,” Berenson notes. “One of the few that has recently come onto the market is a Dunand [lacquered] screen with animal figures. My gallery put it up for sale a few weeks ago, but everyone will be able to see it at the exhibition commemorating the centenary of the [1925] Exhibition, which will open next fall at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.”

Despite its enormous success, the 1925 Paris Exhibition also received criticism. French architects — such as Auguste Perret — protested against the luxurious approach to design favored by the organizers, lamenting that instead of taking the opportunity to align itself with the German Bauhaus movement and champion a form of modernism that was useful to everyone, France had preferred to rethink Versailles.

Perret was particularly bothered by the title: “I would like to know who was the first to put those two words together: ‘art’ and ‘decorative.’ It’s a monstrosity. Where there is true art, there’s no need for decoration,” declared this pioneer of reinforced concrete.

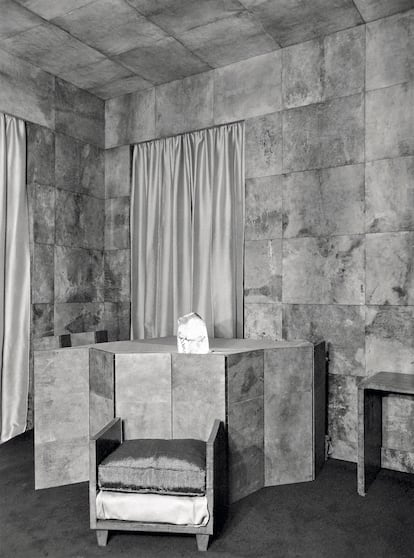

However, not even the veto against Germany prevented ideas like those being taught at the Bauhaus from entering the exhibition grounds. The Soviet pavilion, for example, was conceived as a kind of slap in the face by “the young proletarian republic” against the luxury that surrounded it. This was according to a magazine article published at the time, which described it as a “wooden building painted a neutral color.” Its creator — “Comrade” Konstantin Melnikov — dispensed with any ornamentation or historical references: he simply experimented with planes and volume.

Among the French buildings, the tourist information booth by Robert Mallet-Stevens stood out: a building brimming with technological advances, it was also considered a precursor to the kind of stripped-down Art Deco known as Streamline Moderne. This was a period in the 1930s when buildings were constructed in an aerodynamic style, giving the impression of sleekness and modernity.

“At the 1925 Exhibition,” curator Anne Monier Vanryb explains, “we didn’t see a modernism as radical as that of the Bauhaus… but the next step was already there. Four years later, Mallet-Stevens and other great Art Deco figures who participated in the exhibition founded the Union des Artistes Modernes, in search of a modernism that could be applied to everyday life.”

This group was joined by notable figures of modern design, including Jean Prouvé and Eileen Gray. Another member was the creator of one of the Paris Exhibition’s dissidents: the L’Esprit Nouveau pavilion (the “New Spirit” pavilion). It was so far removed from the prevailing ornamental style that the organizers ordered that a fence be erected to hide it. Its designer appealed to the French government and managed to have the fence torn down, freeing up that strange white box. The tables — with tubular steel legs — and other mass-produced pieces that furnished the interior presented a more modest appearance than Ruhlmann’s designs… although they would still cost a fortune today. Like the pavilion, they were the work of Le Corbusier.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.