The keys to the ‘heavy metal’ philosophy: skepticism, intensity and brutal honesty

Hard rock is also a tool for channeling rebellion and reminding us to stay true to ourselves

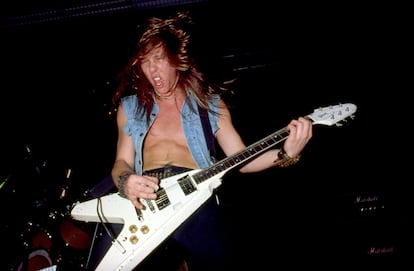

In 1987, Bruque sang “heavy metal is not violence.” Now, so many years later, some voices are wondering if that type of music—a hellish noise for many—hides a luminous mission within its core.

One thing is certain: when faced with life’s desolate landscape of hardship, misery, and unanswered death, millions find solace in the fury of a guitar riff. “Metal is an existential transgression,” explains sociologist and philosopher Hartmut Rosa, author of Angels Sing, Monsters Roar: A Brief Sociology of Heavy Metal, over the phone. “It delves into the abyssal darkness, unleashes the monsters, and carries within it a yearning for redemption. Its music actively seeks a genuine and profound experience.”

It’s a rock to cling to in a sea of nonsense. “It’s more than music; it’s a way of looking at the world with clarity and rebellion, of finding meaning and brotherhood amidst the chaos,” reflects David Alayon, consultant and host of the podcast Heavy Mental, along with comedian Miguel Miguel and engineer Javier Recuenco, in an email. “A heavy metal fan’s way of seeing the world stems from a mix of skepticism, intensity, and brutal honesty. It’s not about denying the darkness, but about facing it head-on, transforming it into strength, and turning pain, rage, or despair into something creative and collective.”

Some people link metal songs to existentialist thought. Journalist Flor Guzzanti writes in Rock-Art magazine that what Black Sabbath or Judas Priest express through distortion isn’t so different from what Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre wrote about: the confrontation with the absurd, alienation, and freedom. Dismissing metal is dismissing philosophy made sound. Alayon agrees. “We share an existentialist vision, accepting that the world is harsh and that the only authentic thing is to stay true to yourself and your people.” And the voice of the recently deceased Ozzy Osbourne singing Electric Funeral comes to mind, encouraging us not to get trapped in a burning cell.

For Andrés Carmona, author of Philosophy and Heavy Metal, the sonic universe of heavy metal culture (in its proto-heavy, thrash, death, grunge, and also hard rock forms, although we’ll leave its definition and limits to the purists) is a valuable tool for philosophical learning. “Even if we don’t realize it, we spend all day thinking about what is good, what is just, what is beautiful. We can’t help but philosophize, and music helps,” he says over the phone. Carmona, a philosophy teacher at a high school in Spain’s city of Ciudad Real, uses the song Gaia, by the Spanish heavy metal band Mägo de Oz, to introduce students to Lynn Margulis and her theory on the importance of cooperation in evolution, and explains the concept of freedom using Ama, ama y ensancha el alma, a song by another Spanish band, Extremoduro, that contains verses such as “we must leave the tarred social path / I prefer to be an Indian than an important lawyer” (by the poet Manolo Chinato).

In an article in Crawdaddy magazine, William Burroughs wrote that rock was an attempt to escape this dead, soulless universe and return magic to the world. If that’s the case, its heavier side seeks collective catharsis through physical experience. Music has the power to transform, and, in the case of heavy metal, “some bands act as a resonating unit that moves the audience, who want to be called upon in search of contact and transformation alongside others,” according to Hartmut Rosa. Because while the present and future are moving toward the abstractions of the digital world, in heavy metal culture, physical ritual is fundamental. There’s the journey, the attire, the pre-show gathering, the explosion of live music experienced in community, and the warm memory afterward when listening to those same songs again alone. “A concert combines feelings, emotions, singing a song with other people at the same time. And there’s also the record, on vinyl or CD, the importance of its covers, its lyrics… I don’t like playlists,” laughs the German sociologist.

In the world of heavy metal, there is light and darkness, angels and demons, heaven and hell, fairies and monsters—a spectacle fueled by an imagination that plays with a certain romantic irony, taking things half-jokingly, half-seriously. But one thing is certain: whether in Germany, Spain, Norway, Japan, Iran, Argentina, or Australia, for the metalhead brotherhood, music is fundamental. According to a study by psychologist Nico Rose—author of Hard, Heavy & Happy, a bestseller in Germany—almost 40% of the 6,000 people surveyed agreed that metal kept them away from dark thoughts, with the feeling that it had “saved their lives at least once.”

The embryo of heavy metal lies in Birmingham, one of the epicenters of the English Industrial Revolution (and with a rich musical tradition in the 1960s). Its leading heavy metal representatives in the early 1970s, Black Sabbath—with Ozzy Osbourne at the helm—and Judas Priest, came from working-class backgrounds or were practically marginalized. And other bands from elsewhere, such as Saxon, Iron Maiden, Slayer, Anthrax, and Metallica, were too. Perhaps that’s why their songs are anthems against the social order, control, and the lack of freedom, and their followers are a vast “community of voluntary outsiders who find in the riffs, the concerts, and the aesthetics of metal a form of belonging without submission. Nobody demands you believe in anything, only feel and resist,” according to Alayon.

But does this community accept everyone equally? Some consider the heavy metal universe to be sexist and heteronormative to the extreme. However, it’s been over 25 years since Rob Halford, the singer of Judas Priest—considered the God of Metal—came out as gay, and artists like Girlschool, Thundermother, Doro Pesch, and Arch Enemy disprove this macho uniformity. But there’s still work to be done. As Guzzanti reflects, “Today, feminist collectives are claiming spaces at festivals, in fanzines, and on online platforms, asserting that resistance must be intersectional. The survival of metal depends on embracing this inclusivity.”

Nietzsche said that life without music is a mistake, a weariness, an exile. We must keep searching, and perhaps it’s not a bad idea to do so through the raw power of heavy metal. “We must fearlessly endure the dance on the existential chasm: this, it seems to me, is the achievement of heavy metal,” declares Hartmut Rosa. As AC/DC sings, “For those about to rock (we salute you).”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.