John le Carré’s tradecraft: A writer who was once a spy

The Bodleian Library in Oxford brings together manuscripts, photos and notes by the author that demonstrate his meticulousness and research

John le Carré, the pseudonym under which David Cornwell (1931-2020) wrote novels that redefined spy fiction and revealed the darkest, brightest, and most ambiguous sides of the pre- and post-Cold War world, made a mistake in 1974 that became a lifelong professional lesson. During a conversation about Hong Kong with a journalist friend who knew the area, the author was warned that a tunnel connected the island to Kowloon Airport in mainland China. However, Le Carré had just submitted for publication one of his most acclaimed books, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, in which one of the characters uses a ferry to make the journey. The writer had based the story on a travel guide.

Obsessed by that mistake, he traveled to the site, personally walked through the tunnel several times, and changed the text of that scene. Much to his chagrin, the correction of the anachronism didn’t make it into the first edition. From then on, he realized that his stories couldn’t be written from the comfort of a desk or a cozy office.

In the jargon of the British intelligence services, MI5 and MI6, the term tradecraft refers to the skills, processes, and methods of modern espionage. Le Carré, who worked for both organizations for a time, also used the word in his novels. It therefore makes perfect sense that the Bodleian Library, one of the oldest and largest in Europe, in the university city of Oxford, has decided to title its new exhibition John le Carré; Tradecraft. This is a double play on words that allows us to understand the meticulousness, work, and obsession over detail of one of the most universal British writers. The process with which he constructed his novels.

The writer studied modern languages and German literature at Lincoln College, Oxford. He had already worked for MI5 there, spying and reporting on leftist students and alleged Soviet agents, something he later expressed regret over. But he maintained a love affair with the university until the end, bequeathing it a 1,200-box archive of all the material that defined his life and work as a writer. “Oxford welcomed my father when he was desperate to escape the malign influence of his own father [a swindler and abuser, as Le Carré described in detail] and couldn’t afford these studies. The Bodleian Library was his refuge, and later the place where he wanted to house his archives. Everything has a certain homecoming flavor,” explains Nick Harkaway, the author’s son and also a novelist.

Until April 6 of next year, Le Carré devotees and those who have not yet had the good fortune to enjoy his novels will be able to see the written, crossed-out, and rewritten manuscripts of classics such as Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, The Constant Gardener, and The Little Drummer Girl; the notes and letters he exchanged with his extensive network of collaborators; personal photos of his family history or his many travels; and the notebooks he accumulated, compiled through arduous research to obtain the most accurate and authentic information on the subject matter covered in each novel.

Le Carré created a vast network of “spies” that allowed him to understand the world. He used academics, journalists, lawyers specializing in human rights or corporate law, activists, or members of philanthropic organizations — whatever it took to expose the Russian mafia, the ambitions of the pharmaceutical industry, arms trafficking, or the dirty war on terror unleashed by the United States after the attack on the Twin Towers in New York.

Federico Varese, one of the exhibition’s curators, along with historian Jessica Douthwaite, was a personal friend of Le Carré and one of the collaborators who helped improve his work. The author approached the young Varese, who was already working on an in-depth investigation into the Russian mafia, to ask for help. He was focused on writing Our Game (1995), a novel based on the bloody Ossetian-Ingush conflict that erupted shortly after the disintegration of the Soviet Union. It was a bridge work, in many ways, whose narrative mastery and the theme it addressed (are there still ideals to fight for in the era of the “end of history”?) demonstrated that Le Carré had much to tell, even though the Cold War had ended. Varese, who also advised the writer on Our Kind of Traitor (2010), had to confirm and reconfirm with his friend what kind of trees there were in the Russian cemetery where a scene took place, what brand of cigarettes the mobsters usually smoked, or how they laundered the money from their activities.

The writer-researcher

“He had a very visual intelligence. In fact, his first vocation was drawing, as you can see in the exhibition. He always wanted to see every place. His work, in that sense, was very similar to that of an investigative journalist,” Varese explains to EL PAÍS. “Going to places, meeting people, conducting interviews. He once wrote that the newsroom desk is a dangerous place from which to observe the world. But he wasn’t an investigator tied to a desk, in any case,” he adds.

Varese summarizes the ultimate goal of the exhibition: to demonstrate that Le Carré was not a spy who became a writer, but rather a writer obsessed with his work who, for a time, worked as a spy. And that he also drew on that experience to create novels and characters that have gone down in literary history.

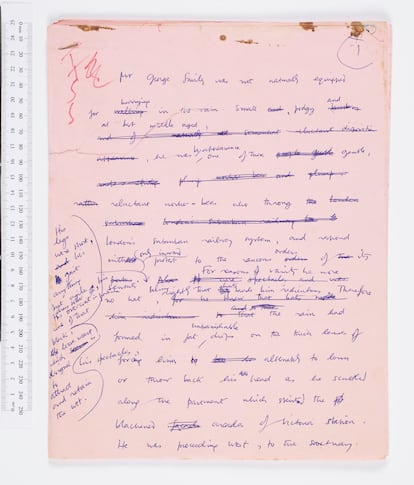

One of the exhibition’s gems is the manuscript in which the writer first describes his most famous character, the agent George Smiley. “Small, podgy, and at best middle-aged,” he roamed through rainy London. “His legs were short, his gait anything but agile, his dress costly, ill-fitting and extremely wet.” The successive deletions, annotations, and corrections on the page give an idea of how the author pursued the perfect phrase. “In the end, he was a writer. He created some of the most important political novels of the Cold War and the period afterward. He was an artist. He wanted to contribute to the canon of English literature. That’s why he not only researched exhaustively, but also wrote and rewrote. I used to read up to six different drafts of each of his novels,” explains the Italian academic.

Le Carré wrote only by hand. His wife, Jane Cornwell, would unravel that spidery jumble of letters, deletions, and corrections to convert it into a typed version. Years later, he would use a word processor. But the writer would review the draft, cut out the paragraphs he wanted to delete or reposition in the text, and tape them together, in a rudimentary copy-and-paste that Jane, however, would later understand. A work of craftsmanship focused on understanding the world and its main drivers: love, ambition, trust, and betrayal. The raw material of David Cornwell’s novels.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.