Ladies, villains, or lolitas: How to spot a cliché about women in film

In ‘Ladies, Villains and Lolitas,’ film analyst Sandra Miret dissects the cinema that shaped us with a feminist perspective, dismantling stereotypes, clichés and notable absences to make us more critical

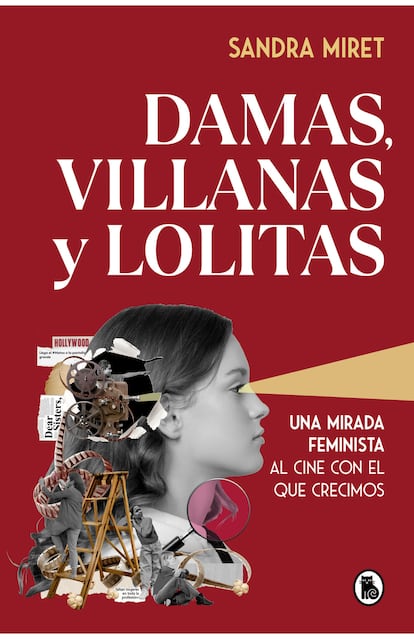

When I ask Sandra Miret to summarize the theme of her new book, Ladies, Villains, and Lolitas. A Feminist Look at the Cinema We Grew Up With (Bruguera, 2025), the author reflects for a moment and admits that she has a hard time coming up with a single message. This isn’t surprising because the book covers a fairly broad field.

Each of its sections focuses on a different aspect of cinema’s relationship with women: from the treatment of women in fiction to the politics that influence awards, from the abuses that occur on film sets to the importance of women behind the camera, including the construction of female characters and the way actresses’ bodies are filmed. Trying to answer my question, the author uses the famous phrase popularized by radical feminist activist Carol Hanish, “The personal is political,” and adds, “And so is cinema.”

Ladies, Villains, and Lolitas is the first essay by Miret, a cultural educator and feminist film analyst specializing in cinema and gender, whom you may have heard of before, given her over 500,000 followers on social media. In it, Miret critically and intimately analyzes audiovisual and cultural content, in addition to recommending films and books that reflect her feminist perspective.

This book represents a further step in her outreach career, and she acknowledges that it is an extension of her Master’s dissertation, which encompasses the studies she completed on gender and communication in 2022. “In it, I analyzed how fiction affects us as individuals and specifically how it affects us in childhood, focusing on the dissemination and near-imposition of gender stereotypes, myths of romantic love, female rivalry, beauty standards, and so on,” she explains. She acknowledges that she addressed this work because she always found it striking “how easy it is for people to limit cinema to mere entertainment, when it has been a faithful companion and perpetrator of the patriarchal system and rape culture.”

We are what we see

Miret’s book begins with a general overview of the audiovisual situation many of us encountered in our childhood and adolescence. Most of us grew up watching princesses in distress and heroes rushing to save them, with stories in which gender roles were so limited and clear-cut that they normalized a completely male (and white and heterosexual) perspective.

How can we forget the very white, thin, and pretty protagonists of series like Hannah Montana or Wizards of Waverly Place? Things didn’t improve, according to Miret, when we grew up and started watching movies intended for adults.

In series like Sex and the City, Charmed, Friends, or Desperate Housewives, and hundreds more, sexual violence against women was normalized and women’s bodies were hypersexualized, even if it was completely unnecessary for the plot. To top it all off, the cinema of the time that was classified as “feminine” was silly and romanticized, and even if it worked financially, it only perpetuated those gender stereotypes even further.

These differences were evident, according to the author, not only in the importance of the characters or their actions, but also in the way the female body was filmed. Shots were carefully chosen to “cut” the girls into pieces (breasts, hips, backsides), focusing on men’s sexual preferences and resorting to film “tricks” like slow motion to heighten the pleasure of the male gaze.

Today, they’re almost visual jokes, but they were ubiquitous in the past. There are hundreds of examples, but how can we forget the classic shots of a woman pushing her hair back from her face or emerging from the sea, repeated ad nauseam, for example, in the James Bond saga.

However, the author points out how these mechanisms are still used today, and gives as an example the way in which the character of Cassie (played by Sydney Sweeney) is portrayed in Euphoria, resorting to the same sexist patterns that have been used in cinema for decades.

Miret does though acknowledge that some important progress has been made in recent years. As an example, she looks at how women and sex were treated in the early seasons of Game of Thrones (released in 2012), which were rife with unjustified female nudity and sexual scenes in which women’s bodies were fragmented and where hair-pulling, groping, and so on were prominent. Following criticism, these types of scenes, which were characteristic of the series, practically disappeared in later seasons.

Female archetypes and notable absences

“It was quite shocking to realize how racist and xenophobic the cinema I grew up with was,” the author says. “It was clearly a very white cinema, and the presence of people of color was largely through a white, very limiting, stereotype-filled, and often racist lens. I think it’s something we’ve normalized so much that if you spend an hour or two reviewing all the films and TV shows from your childhood, especially Spanish ones, and focus on the characters of color, you’ll realize a lot.”

Miret dedicates the second part of her book to unpacking the many archetypes and plots unfavorable to women that have traditionally been used in film and television. A list the author acknowledges grew longer the more she researched, and she ultimately decided to focus on those most prevalent in her childhood and adolescence.

Among the most notable is one we’ve already mentioned, the damsel in distress, the princess trapped in the tower whom the knight in shining armor comes to rescue, and all its updated versions, from King Kong to Star Wars, Shrek, and Batman. The list is endless.

But Miret points out many other archetypes such as the “Manic Pixie Dream Girl,” that lively and bubbly girl who only exists in the imagination of the scriptwriters and who would be embodied by characters such as Penny from Almost Famous or Holly from Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

Another — one of the most problematic today — is the Lolita, the incredibly sexually attractive girl, who is consciously or unconsciously manipulative. But there are many more: the Bad Girl, the Femme Fatale, the Warrior, the Badly Fucked Business Woman, the Spinster, and a long list of others.

In her analysis, Miret also examines racialized people, those belonging to the LGBTQ+ community, those with non-normative bodies, or who are not young, and who, if they are also women, have been even more noticeably absent from films and television series, or have been represented through a heteropatriarchal prism.

Times are changing

Despite the criticism, Miret acknowledges in the final part of the book that the situation has gradually improved over time. Perhaps with a bit of a drag, as in the case of Game of Thrones, and also with numerous setbacks, such as with Euphoria.

It’s not hard to see: just a glance at current film and TV shows is evidence of this. There are more and more female directors offering their own perspective, far removed from the male gaze; abuses committed in front of and behind the camera are being reported and condemned (although many probably remain unpunished); the role of intimacy coordinators, who ensure actresses feel comfortable when filming sexual or violent scenes is becoming more widespread; and new stories are being told featuring characters outside the norm who were previously invisible.

In short, things have changed a lot, but we’re far from the end of this journey yet. Occasionally projects appear, even very successful ones, like Élite or Emily in Paris, which seem to be from another era in terms of their treatment of women.

Precisely thanks to the work of educators like Miret, and the dedication of millions of other women, anonymous or not, the clichés and stereotypes that we have dragged along for so many years will gradually be left behind and — with a bit of luck and despite the forces that will surely push in the opposite direction — new generations of girls will see the archetypes and clichés of the cinema and television of the past as something completely outdated and will even be able to enjoy them, while being aware of everything that is not right about them.

Asked what she would like readers to take away from her book, Miret explains that her goal is to “spark conversation. I would like to sow doubt and critical thinking so that people understand the importance of fiction and its consumption, so that they question what they see and what they have seen,” she notes.

“One of the things I’m most eager to achieve with this book is that the people who read it realize how important the audience is, and the audience is all of us, especially us,” she continues. “And I say ‘especially us’ because film has long been a male industry and sector, and largely remains so, as is the space given to film criticism. A lot of critical power has been taken away from women. So I hope that those who read the book realize how important every film and series they decide to watch is and take into account who directed, wrote, and starred in it and how we talk about these products afterward. Because cinema isn’t mere entertainment. Making a film and releasing it to the world is political, and the public’s decision to go see it and recommend it is also political.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.