From clown to ethical role model: How Tom Hanks got the whole world to love him

He’s the epitome of the ‘good American,’ who has managed to keep his distance from controversy thanks to simply doing what we expect of a star: deliver hit after hit for 40 years. His latest film ‘Here’ could be another cause for affection

When the father of Tom Hanks (Concord, California; 68 years old) was just a boy, he saw his own dad killed by a day laborer in a fight on the family farm. Amos Meffor Hanks was just eight years old at the time, and was the only witness to the murder. He was forced to testify three times, but the killer went free. The events resulted in a profound sadness that stuck with him throughout his life. “It robbed him of a sense of fairness in the world. It was a black mark of injustice and unfairness that landed squarely on his young shoulders,” Tom told Graham Bensinger in 2020 on In Depth. “My dad wanted to write, he had great artistic desires, but life didn’t deal him the cards in order to pursue them.”

That shadow left its mark on the actor’s childhood — a slight mark, but all the same, it is there, behind the frank and mischievous smile that has earned him the titles of “America’s dad,” “the nice guy,” and “the mayor of Hollywood.” He has a subtle dark side. “The reason he’s a movie star is that he’s complex,” says Sally Field, his co-star in Punchline (1988), a tale of comics that was underappreciated when it came out. “Yes, it’s so fun and easy to be around him, but you know that in the background, there’s something dark. He has a sad side. It’s what makes him so convincing on-screen.”

The origin of this darkness can be found in Hanks’ erratic childhood. His parents got divorced when he was five years old and while his little brother stayed with their mother, he, his older sister and his other brother traveled the country with their father. “I moved about a million times,” he told Rolling Stone. “I think we moved every six months of my life.” That didn’t just make it difficult to hang onto friendships, it also forced him to get rid of material possessions that were important to him, which perhaps explains his mania for collecting things (he has a considerable assemblage of typewriters) and his need to seek out physical anchors. That nomadic lifestyle impacted his college years.

“I was a geek, a spaz. I was horribly, painfully, terribly shy. At the same time, I was the guy who’d yell out funny captions during filmstrips,” he said. Hanks was one of those kids whose parents’ work forced them to raise themselves — but he doesn’t harbor them any ill will. With time and after becoming a parent himself, he explained, he was able to better understand their difficulties. One of his sons, Chet Hanks, is especially problematic. He’s been implicated in an episode of domestic violence, has had problems with drugs, and was accused of flirting with the white supremacist aesthetic. Hanks managed these situations with discretion, and served as Chet’s support system.

Hanks has always located the roots of his success as an actor in his childhood, whose unconventionality left him flexible and with the confidence he needed to thrive in any social interaction. “Acting classes looked like the best place for a guy who liked to make a lot of noise and be rather flamboyant. I spent a lot of time going to plays, seeing Brecht, Tennessee Williams, Ibsen, and all that.” He wasn’t a bad student, but he did like theater more. His fondest memory was of the three seasons he spent at the Great Lakes Shakespeare Festival. A co-worker recalls how one night, the entire cast sat down to watch a Saturday Night Live hosted by Steve Martin. Hanks pointed to the television and said, “Someday I’ll host this show.” And he has — 10 times.

His was not an immediate, meteoric rise. His first role was on the slasher film He Knows You’re Alone (1980). He also had small roles on The Love Boat and Happy Days, where he worked with Ron Howard. Hanks made such a good impression that the young actor, who eventually became a director, thought of him when Howard was preparing to make Splash (1984). Hanks was originally set to play a supporting role, but wound up taking the lead when the director’s first choices declined the part. “The reason I got to do it was that a lot of big actors turned it down,” he said.

He was the first choice for the role of Josh Baskin in Big (1988), but the filming for Turner & Hooch prevented him from accepting the gig, and the part was passed onto Robert De Niro. When The Godfather star demanded $6 million the role, it was kicked back to Hanks. Big allowed the wider public to get a glimpse of the extraordinary actor behind the comedian they already knew. The movie got him his first Oscar nomination. He once again worked with Penny Marshall on A League of Their Own (1992), a role he fell in love with despite it being originally intended to be an older character.

By that point, he’d made it through the biggest failure of his career, The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990), an adaptation of the successful novel by Tom Wolfe that also featured performances by Melanie Griffith and Bruce Willis. It had been expected to be a hit, but flopped. Wolfe’s book hadn’t pandered to its protagonists, but Warner Bros thought that no one wanted to see Hanks as a cynic, transforming his character into a sweet guy like the ones he typically played and rendering the vitriol of the original work toothless.

In the 1990s, Hanks embarked on a new chapter of his career with Nora Ephron. The director and screenwriter, who had originally thought of him for the role that Billy Crystal wound up playing in When Harry Met Sally (1989), turned him into an unexpected rom-com star. Hanks, the guy who once described himself as having “a big ass and fat thighs… a goofy-looking nose, ears that hang down… and a gut I’ve got to keep watching.”

Sleepless in Seattle (1993), a classic that reinvented the box-office smash, began with a disagreement. Ephron had written a scene in which Hanks’ character turned down a date so as not to upset his son, but Hanks asked her to make some changes. “There is not a father on the planet Earth who is gonna give a rat’s ass what his son thinks about him going out with a woman. Because you know what that father wants to do? He wants to get laid,” he argued — and, eventually, convinced Ephron. It was then that a relationship of mutual trust was forged, one that led the same team to team up years later, with the same success, with You’ve Got Mail (1998), a version of Lubitsch’s classic The Shop Around the Corner.

By the time his second collaboration rolled around with Ephron, with whom he maintain a creative relationship until her death, Hanks was already an established star. He’d taken on what was considered an unthinkable risk with Philadelphia (1993), a cinematic sneaker hit that won him his first Oscar. Under the direction of Jonathan Demme, he displayed what was seen as courage at the time in taking on a project that explored HIV, back when the disease’s name was not even being mentioned by political leaders. Hanks had always been Demme’s first choice for the role, just as he was Robert Zemeckis’ choice for Forrest Gump (1994), a film that no one saw coming for its naivete and candor.

However, it proved to be a great success, inscribing a handful of lines in our collective movie memory for all time. It also brought Hanks his second Oscar (he won them in consecutive years, something only Spencer Tracy has achieved). But the actor still carries a chip on his shoulder from Gump — he’s annoyed at its lukewarm critical reception. “There’s books of the greatest movies of all time, and Forrest Gump doesn’t appear because, oh, it’s this sappy nostalgia fest. Every year there’s an article that goes, ‘The Movie That Should Have Won Best Picture’ and it’s always Pulp Fiction.”

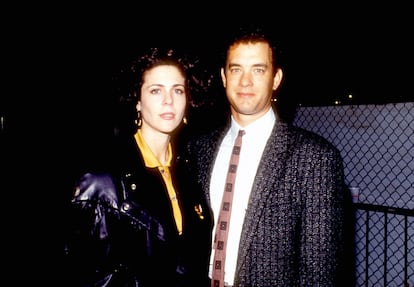

Underrated or not, Hanks was able to make any movie he wanted and in 1995 he chose to play Jim Lovell, the astronaut that captained the Apollo 13 mission. A hero on a failed quest, a statement of intent. The constant in this phase of his career was that he tried to play people who had a positive message, who help to build the society they believe in, and actively fight for it. Characters like Captain Phillips, Ben Bradlee from The Post, Mr. Rogers in A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood and cowboy Woody from Toy Story. They’re characters that, as producer David Geffen tells it, make Hanks look like “a good citizen, someone you can admire without feeling foolish.” He’s drawn to the heroism of the common man, and to entertaining the public. He’s a screenwriter, director and producer. Alongside his second wife, actress Rita Wilson, he’s produced two feel-good classics, My Big Fat Greek Wedding (2002) and Mamma Mia (2008). Hanks has optimism in his veins.

Despite his unquenchable thirst for justice and support for varied social causes, he’s not one to give his opinion via smart phone and harbors a distrust for the immense power of social media, which he says has taken away currency from truth. “That is only going to be altered when enough people say, ‘[Expletive] that, I’m not going to pay any attention to social media ever again,’” he said. That’s one of the reasons he stopped using X, after having been a frequent poster of fun stories about lost objects on the platform. “I’d post something goofy like, ‘Here’s a pair of shoes I saw in the middle of the street,’ and the third comment would be, ‘[Expletive] you, Hanks.’ I don’t know if I want to give that guy the forum. If the third comment is ‘[Expletive] you, you Obama-loving communist,’ it’s like, I don’t need to do that.”

Hanks avoids conflict, on and off screen. “I’m not interested in malevolence; I’m interested in motivation,” he’s said. That’s why his performance as Colonel Tom Parker in Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis took some fans by surprise. But Hanks doesn’t consider Parker a bad guy, just misguided. He simply doesn’t accept unequivocal evil. It has been said that on the set of Charlie Wilson’s War (2007), he declined to have his character appear snorting cocaine, out of fear that he would come across as too unlikable.

The recently premiered Here sees Hanks reunite with Robin Wright and Robert Zemeckis, some 30 years after Forrest Gump. In the continuation of the original film’s plot, its characters are a happy couple whose life we see take place across several decades in a single location. Thanks to the miracles of CGI, we once again see Hanks as a young man, although he clearly doesn’t subscribe much to nostalgia on a personal level. During the promotion for the film he said, “It’s good to look young again, but I would rather be as old as I am.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.