From the highest-paid actor in Hollywood to straight-to-video B-movies: The rise and fall of Bruce Willis

In the last eight years, the actor has made 29 films, 23 of which never made it to the cinema. The parody award show the Razzies has also given the actor his own category for ‘worst performance’

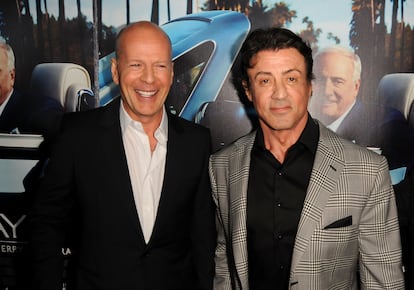

In 2013, Rocky star Sylvester Stallone described Bruce Willis as “greedy and lazy,” adding that this was a “sure formula for career failure.” Stallone had offered Willis $3 million for three days’ work on The Expendables 3, and Willis had asked for $1 million more. Almost a decade later, Stallone’s observation seems the only possible explanation for Willis’s fall. Once the highest-paid actor in Hollywood, the Die Hard star now has his own category in the annual Golden Raspberry Awards, a parody award show – also known as the Razzies – that honors cinematic under-achievements. The category is “Worst Bruce Willis Performance in a 2021 movie.” There are eight candidates. All of the films went straight to video. How did it come to this?

Perhaps it all started at some point in the 2000s. Willis was already showing signs of tiring of fighting against his destiny, of having the critics against him and the public on his side only when playing underdogs in action movies. The only thing left was to exactly that; the kind of cinema that was expected of him. He started to accept parts in generic action thrillers, acting with an earpiece so that he wouldn’t have to learn his lines.

Willis’s last attempt to claw back some prestige was in 2015. Having started out in off-Broadway productions, after 30 years without cracking the boards, he returned to theater in an adaptation of Misery. The critics shot down his performance with adjectives such as “inert” and “empty.” Since then, Willis has been staunchly a straight-to-DVD actor. In an industry dominated by franchises, Willis decided he could become one, with Randall Emmett as the wholesale manufacturer of the product.

Crossing paths with the producer was the worst thing that has happened to Willis’s career, but the best thing that has happened to his bank account. According to industry website Vulture, Emmett has developed a system for mass-producing movies in which he gathers together a team of people looking to embellish their CV, convinces a veteran star (John Travolta, Nicolas Cage, Al Pacino, Robert de Niro, Steven Seagal, etc) to put in a couple of days’ work for $1 million and then uses their face on the promotional posters to land international distribution deals. The star tends to appear in just three scenes, at the beginning, in the middle and at the end of the movie. In Hard Kill, Willis is on screen for a total of seven minutes; in Extraction, eight, and in Survive the Night, just under 10.

In the last eight years, Willis has made 29 movies, 20 of which were Emmett productions. Twenty-three went straight to domestic viewing platforms and 16 have a less-than 10% approval rating on viewer-aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes. While he would surely accept meatier roles if they were offered, the industry doesn’t seem to know quite what to do with him, leaving Willis with a choice of kicking his heels at home or making easy money on movies where he is still the king. Most veterans are increasingly choosing the second option.

It is rumored Willis has financial issues that leave him with little choice but to accept such roles, much like Cage, De Niro and Pacino. The B-movie industry represents quick cash. A Hollywood production, which would pay considerably more, may take years to put together. One of Emmett’s movies can be set in motion within weeks. And the prolific producer isn’t concerned about annoying his investors, directors or screenwriters, while shaving every available dollar off costs. A producer who worked with Emmett told The New York Magazine that projects involving Willis have “a bullying kind of exploitative nature” because shooting days are reduced when the movie is in production. On Out of Death, Willis decided to cut his contribution from two days to one, leaving the director to squeeze as many scenes out of him as he could.

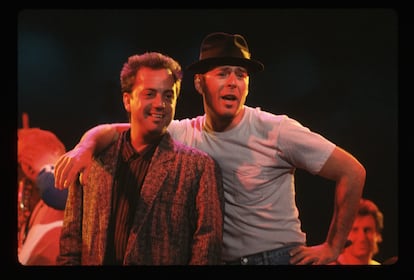

“Why does Bruce Willis keep making films he clearly hates?” asked Esquire magazine in 2020. Willis has always seen himself as an outsider with the system against him, according to people close to him in a 1991 Vanity Fair profile. When he was young Willis was painfully shy and had a stutter, an affliction the theater cured him of, he told journalist David Sheff in 1996. From there, Willis shaped his persona around his physique: a sardonic, ironic guy who didn’t give a damn. That is the persona that the public subsequently came to know as Bruce Willis, and throughout his career, he has played various versions of himself. The first was in the TV show Moonlighting, his big break.

The show’s executives wanted an established star, so Willis had to do 11 auditions to convince them of his suitability. During the final one, a woman stood up and said: “I don’t know if he’s a leading man or not, but he looks as though sleeping with him is fucking with danger.” He got the part.

However, despite the success of Moonlighting, two box-office bombs helmed by Blake Edwards, Blind Date and Sunset, as well as his decision to release a record called The Return of Bruno, turned Willis into a running joke for the intellectual elite. Willis was an atypical, modern leading man, a blue-collar rogue who Hollywood had admitted but would never let him forget he was there on borrowed time. When he was paid $5 million for Die Hard, the biggest paycheck ever in Hollywood at the time, the industry and the media went wild. “If Willis gets $5 million,” wondered The New York Times, “how much for [Robert] Redford?”

The distributor of Die Heard, 20th Century Studios, insisted Willis was worth it. Only he was able to carry off an action hero who had walked in off the street, so hapless and cynical that he seemed to nod to the fact he was in a movie. In Die Hard 2, Willis’s character John McClane asks: “How can the same thing happen to the same guy twice?”

Unlike Stallone or Arnold Schwarzenegger, Willis’s muscles appeared vulnerable, as though every hit genuinely hurt. Three years after the hugely successful Die Hard, the media were eager to announce the end of his career. The failures of The Bonfire of the Vanities, The Last Boy Scout and, above all, Hudson Hawk, which he co-wrote, seemed to confirm that Die Hard and Die Hard 2 had been a lucky swing. Willis became hostile to the press, which he said was bent on bringing him down. It was not entirely without basis. Reporters described him as “a star who eats with his hands” and “an actor who has made a fortune because Hollywood has become a corporation.” He adopted a defensive strategy in interviews, rehearsing his responses not to give anything away, to maintain the public image of Bruce Willis, to make sure he didn’t stutter.

His career was resurrected in 1994, when Quentin Tarantino cast him in Pulp Fiction. However, despite the movie’s huge success, Pulp Fiction started a pattern in Willis’s career from then on: even when he was in a hit, the press would focus on other aspects of the movie. In this case, that focus was Travolta, whose own resurrection at the hand of Tarantino eclipsed Willis. Six years later, when The Sixth Sense was well-received by critics and at the box office, all the talk was of newcomers M. Night Shyamalan and Haley Joel Osment, as though the movie was a success in spite of Willis, not because of him.

More hits followed: The third Die Hard installment and Armageddon, which were the highest-grossing movies of 1995 and 1998, respectively. These served to confirm that what the public wanted to see was Bruce Willis playing Bruce Willis. Still, he had to hide the fact that he craved the respect of critics, that he had artistic concerns and that he wanted to show his versatility as an actor. Willis has one of the most varied filmographies in Hollywood. Between 1992 and 1999 he played a surgeon in Death Becomes Her, an imaginary friend dressed as the Easter bunny in North, a gangster in Last Man Standing, a time-traveling convict with paranoia issues in 12 Monkeys and a car salesman on the verge of a nervous breakdown in Breakfast of Champions. He even played himself in a parodic light in The Player. In none of those productions was he the director’s first choice for the role – he had to fight for the parts and take a pay cut to make the movies.

Perhaps through so much pretending not to give a damn, Bruce Willis has ended up genuinely not giving a damn. When all is said and done, the movies Willis makes now only exist so that Bruce Willis fans get to see Bruce Willis in movies. As actor Michael Caine famously said of his participation in the universally panned Jaws: The Revenge, which has an approval rating of 0% on Rotten Tomatoes: “I have never seen it, but by all accounts, it is terrible. However, I have seen the house that it built for my mum, and it is terrific.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.