From working-class Batman to a Wonder Woman pursued by immigration authorities: Superheroes work to reinvent themselves

Comic icons are in the hands of creative teams set on reimaging their basic biographies in the hunt for new readers who could be intimidated by complex backstories. Can they make the shift without altering their key essence?

Many nights, Peter Parker can’t sleep — and not because he’s out fighting crime in his instantly recognizable Spandex suit. He doesn’t even own one, not to mention the fact that he’s actually incapable of launching spiderwebs from his extremities. This Parker’s struggle is with the existential weight of being 35. Constant coffee consumption gets him through the day, but his restlessness always returns. He has a wife and two kids who he loves, a job as a photojournalist — many reasons to be satisfied, and yet, something is missing and he doesn’t know what. But for readers of Ultimate Spider-Man, the answer is clear: he was never bitten by a radioactive spider in his youth. As a result, Parker can’t turn into the celebrated wall-climber. In the character’s latest reinvention by Jonathan Hickman and Marco Checchetto, he is not a superhero. Yet.

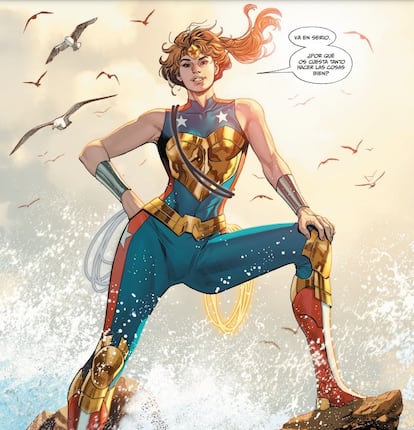

Neither is Wonder Woman. Or at least, she’s not seen as such by the U.S. government. To the contrary, in recent Marvel comic books written by Tom King and drawn by artists like Spain’s Belén Ortega, she’s at risk of being deported as an undocumented migrant, along with the other Amazons. It’s a new world, and the legends of the strips are changing along with it. After all, the new projects seem to tell us, in order to save the world, our saviors must first understand it. Marvel calls its new series Ultimate. DC has dubbed theirs Dawn, to be followed by the Absolute and All In series. The two comic book giants are looking to modernize their icons, to breathe youth and originality into characters who have reached retirement age or are older still. To simplify chronologies that have grown to levels of complexity that can intimidate the most seasoned fan. In short, to engage new and old audiences. And of course, to keep sales up.

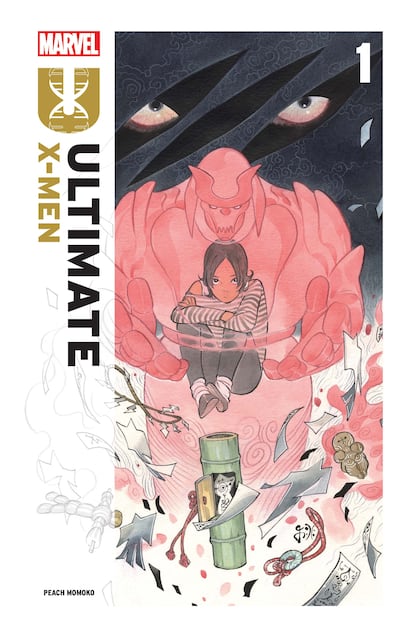

“All the aspects of it hold true, but I would say that almost certainly, the least important is the main thrust. Artists are looking to follow the precedent, in a creative way,” reflects Sean Howe, author of the well-received Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, published by Harper Perennial. It’s true that some of these new premises can be surprising. In Scott Snyder and Nick Dragotta’s Absolute Batman 1, Bruce Wayne lost his father, but not his mother. He’s also lacking that multimillion-dollar fortune, introducing us to an unprecedented working-class Dark Knight. The Absolute version of Wonder Woman grew up in the Greek underworld and its Superman, who will debut on November 6, likewise promises to shock the comic book faithful. From Japan comes an X-Men reimagined by Peach Momoko, sporting a manga aesthetic and shorn clean of some of the franchise’s pillars, including its leader Professor Charles Xavier. “To consider what the genesis of superheroes would be like in a completely new world is a fascinating exercise,” says Hickman, who led the team responsible for Ultimate, on the Marvel website.

“These publishers are facing a strange predicament: they specialize in serialized narratives that owe much of their power to their increasing complexity. And, at the same time, that complexity is becoming increasingly difficult for the public to absorb. Attracting new readers becomes even more of a challenge because of all that baggage,” says Howe. One need only look to the Ultimate imprint itself for proof. It was first trotted out in the early 2000s to house an earlier modernization of its characters. As such, the Marvel website now provides an explainer of “everything there is to know” about the imprint’s return, comprised of no less than 22 paragraphs, featuring mentions of several parallel universes. And this is a relatively new series.

Such intricacy does beg for a reset every now and again, along with the introduction of superheroes more suited to modern times, like Miles Morales, Ghost Spider, Ms. Marvel and the Brazilian Wonder Woman, Yara Flor. When it comes to modifying the old classics, however, publishers often opt for tweaks over rehauls. Or complete reworks that, in a certain sense, keep everything just as it was. “It’s largely about props. The essence should remain the same, tell the same story, but in a different way, for new generations,” says Alejandro Martínez, editor of Panini Comics, which publishes Marvel projects in Spain. “It’s a larger creative universe shared with other artists, but I still feel independent in a certain sense. And at the same time, there are minor rules you have to respect so that it keeps representing Marvel,” Momoko told Screen Rant.

Momoko’s new X-Men are still marginalized figures, in search of belonging amid a world that rejects them. Now, they’re dealing with the lights and shadows of social media, and the Japanese artist has introduced body horror into the saga, but she was blocked from involving certain characters, their use vetoed by the publisher. Ultimate’s Spider-Man learns a familiar lesson to readers of his 1962 debut by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko: “With great power comes great responsibility.” Only this time, the teaching doesn’t come from dead Uncle Ben, who is alive and well and has become an investigative journalist.

“I wanted to start from what we love about these characters and go from there,” Joshua Williamson, one of the principal writers behind Dawn of DC, told web publication Comic Book Resources. King told Screen Rant that his Wonder Woman came from his reflections on what made the character stand out. He concluded that Batman protects justice and Superman, the status quo. The Amazon, in contrast, “is against the establishment. She’s rebellious, she stands up,” he says.

Martínez thinks back to what was happening in the real world when comic book legends were first created. Many Marvel icons made their debut when the United States was mired in the Vietnam War and the student protest movement was gaining popularity. Some of DC’s most famous characters popped up during World War II. The young people who first read these opening chapters are now grandparents. Superheroes never leave anyone behind, especially not their original followers — but they do need to speak to their grandchildren. Today, they have an unprecedented opportunity, in terms of both editorial impact and business revenues: for the first time, three generations of audience are here for the taking. Check out the number of Spider-Man and Ghost Spider backpacks at elementary schools these days and you’ll see that some of these characters have never been more relevant.

“They’re living heroes, and the dance by creative teams has always been present. Every writer who takes over a collection for a long amount of time decides where to take it. Within the margins of such large licenses, I consider them authors’ comics. If the creators didn’t put their soul into what they do, these comics would have felt empty for decades,” says Martínez. Even so, Howe says that since the 1980s, this kind of project has “increased significantly.” Great encounters, intertwined comics with dozens of characters, anthological clashes with (almost) unbeatable villains. Campaign expansions like Secret Wars, Age of Apocalypse, and Civil War have dominated entire summers for Marvel fans who today sport gray hair and baby strollers. At the same time, DC has unleashed a wide variety of Crisis storylines (Identity, Dark, Infinite Earths). Both companies’ marketing campaigns deploy epic editions on a nearly monthly basis. Earth-building events are hyped until the next, even more epic one comes out. And once they climax, more often than not with the death of a major player, they serve as the perfect pretext for yet another resurrection from the ashes.

Many of these projects constitute a new beginning for superheroes, and for the readers who feel intimidated by decades of their backstories. According to Howe, the same strategy is being implemented by Hollywood, which serves up simplified servings of famous characters. Proof of the approach’s success lies in box office returns and the impact such movies have on popular culture. At least, for now. The complex web of plots that entangle comics can also ensnare icons of the silver screen, and both Marvel and DC are currently looking for new chapters in their cinematic universes as well.

“We are in a capitalist world. It’s unfair to say that Marvel is just trying to make money. I don’t believe that it is commercializing more than any other publisher. All comics should sell themselves, if they don’t, there’s no industry. At the end of the day, at any rate, the readers decide,” says Martínez. And now, they can be of any age — though there are few missions as complicated as appealing to three generations at once. In many households, that’s a tall order. One that calls for a superhero.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.