‘We could be the biggest band of all time’: The fall of the Stone Roses, the group tipped to be the new Beatles

The Manchester group was hailed in the late 1980s as the iconic British band for a disenchanted generation. When they released their second album 30 years ago, everything fell apart

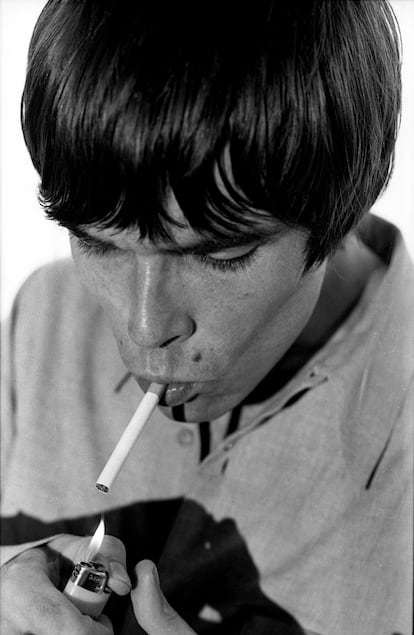

“We’re the most important group in the world, because we’ve got the best songs and we haven’t even begun to show our potential yet,” Ian Brown, vocalist of the Stone Roses, told New Musical Express in December 1989. “The past was yours/but the future’s mine/You’re all out of time,” he sang symbolically in She Bangs The Drums, one of the most celebrated singles from their eponymous debut album. The Stone Roses ushered in the 1990s hailed as the great hope of British rock. Five years later, on December 5, 1994, their long-awaited second album arrived. It was titled Second Coming, comparing it, with the usual immodesty of the group, to the second coming of Jesus Christ. However, it was received with a mixture of lukewarmness and disappointment. It was not a huge commercial success (it sold a million copies), but its commitment to long, brick-like compositions of onanistic guitar-driven rock in the style of the 1970s did, in one fell swoop, extinguish all the expectations that had been created around the band.

“It is one of the most insufferable albums I have heard from a group with a great debut. The total and absolute verbalization of their detachment from the muses of inspiration is incomprehensible. In my opinion, it was a recording death,” says music critic Marcos Gendre, author of the book Mánchester. El sonido de la ciudad (Manchester: The Sound of the City). For Jorge Albi, co-author, with María A. Román, of the book The Stone Roses (1995), it is an album that “is not up to par. If it had not taken so long and they had made more glorious songs like those from the first record, they could have achieved something more, but what they did on this album was a bit of a bore.” A year and a half later, the band broke up.

The future might have been theirs, but by the time Second Coming saw the light of day, their time had already passed. The so-called Madchester sound they had pioneered no longer interested anyone. What they might have become in the end was their biggest fans, the Gallagher brothers of Oasis, who four months before Second Coming was released, beat them to the punch with Definitely Maybe and an equally ambitious plan for world domination. Both Liam and Noel have always said that they wouldn’t have been there if it weren’t for the Stone Roses.

“When I first heard their song Sally Cinnamon I knew what my destiny was,” Noel said at the time, while Liam says the Stone Roses were the first group he saw live, and that it made him want to get up on stage. More surprisingly, in the documentary Made Of Stone, directed in 2012 by Shane Meadows (This Is England), the Oasis vocalist declared on camera that “the Roses,” as they were popularly known in the United Kingdom, were the best group from Manchester. In the end, it can be said that, unintentionally, the Roses laid the first stone from which Britpop blossomed, but the revolution they promised to be turned out to be a colossal fiasco. What happened?

Manchester, 1980s

YouTuber Víctor Amorín, on his Music Radar Clan channel, pointed out a factor that has not been talked about much. The Stone Roses were born in Manchester in the early 1980s at the same time as New Order and The Smiths. In fact, Peter Hook (of New Order) produced one of their first singles, Elephant Stone, and some of its members shared early groups with members of the Smiths. However, in 1989, when the Stone Roses’ first album was released, the Smiths had already developed their entire career and Morrissey had released his first solo album. Amorín’s thesis is that Ian Brown (vocals), John Squire (guitar), Gary “Mani” Mounfield (bass) and Alan “Reni” Wren (drums) were very ambitious, but were never willing to take on the responsibility of being ambitious. In other words, they had the attitude, but lacked the work ethic that others of their generation possessed. They were able to arouse the curiosity of the British media, but they did not live up to expectations.

Why did U.K. music critics place so much hope in them in the late 1980s? “Everything was exaggerated, because it was a time when the media was looking for someone to occupy the throne that the Smiths had left vacant,” notes music critic Carlos Pérez de Ziriza. “They had the merit of fusing, like no other group, the British pop heritage of the 1960s and its most exquisite melodic tradition with the new rhythms emanating from Manchester, favoured by the rise of rave culture, acid house, and that new lysergia that had driven the second summer of love, that of 1988.”

For Marcos Gendre, “they were hopeful, but, beyond the hymns they pulled out of their sleeves, the only song that could really determine renewed paths was Fool’s Gold, the single they released immediately after the first album.” According to the journalist, “the golden age of the Stone Roses marked the beginning of the retro trends of the 1990s.” They benefited from the fact that, “within an indie scene as anti-charismatic as the one of that time, they recovered the shamelessness of punk in their way of acting, and some musical aesthetic signifiers that referred to The Byrds, Jimi Hendrix, and psychedelia. Although in their new version, instead of flowers, there was graffiti and, instead of LSD, MDMA.”

Their social impact on the U.K. was brief but intense and profound, associated with the rave scene. They were, along with Happy Mondays, the first band to fuse guitar music with the new dance culture. Their aesthetic set the trend, with their album covers, their guitar and bass painted by Squire in a style similar to Jackson Pollock, Reni wearing those bucket hats that were imitated ad nauseam by his followers, the baggy t-shirts and baggy trousers that also defined an era. All of this reached its highest social moment in the summer of 1990 with their triumphant concert at Spike Island, defined as “the Woodstock of the baggy generation,” although many remember it as a fiasco, more like Altamont but without any fatalities, an organizational disaster with terrible sound, but on the stage Brown could be seen holding up a huge globe in his hands, in a “the world is ours” style.

Added to this is the hooliganism they displayed. In one of their most famous performances on British television, they played at such a high volume that they blew the fuses on the set. They went even further when, angry with their first label, FM Revolver, for re-releasing a video clip of the single Elephant Stone without their consent, they vandalized their offices and their employees’ cars by pouring buckets of paint over them. They were taken to court and only escaped jail because, in the judge’s opinion, this would serve to give them more notoriety, so he handed them a hefty fine and sent them home. In this regard, Jorge Albi is very critical of “the idea of all these artists that the worse they are, the better, the whole ‘we’re really cool, and it’s going to take us all this time to create our great masterpiece’ thing, which in the end only conceals arrogance.”

The years of drought that burned the group

In reality, it was a myriad of circumstances that led to the five years of silence between the first and second albums. Some say that their manager at the time, Gareth Evans, mismanaged the band’s career badly, and the Roses went back to court, entering into litigation with the independent record label Silvertone to get a release so that they could sign with the multinational Geffen. While this caused more and more delays in the recording of the new album, the members of the group were left unsure of what to do, stopped playing live, experienced a creative block and began to prioritize other things.

Some of them had children, and others, according to urban legend, went around the bars saying that the Stone Roses were going to be the band that would go down in history for recording that legendary album and never doing anything else. The fact is that they arrived for the recording sessions for Second Coming already reeling. “There were things that were out of our control, like the whole trial thing, and it was never the same again. Once you lose that moment, it’s hard to get it back,” Mani said in Shane Meadows’ documentary. “Making the second album ended the band in a way. Nothing was ever the same again. After Silvertone left, the live shows were over and everything pointed to the fact that we were being manipulated. We tried to get rid of the manager, and when it came time to record we were half lost,” said Squire. Brown summarized: “We stopped enjoying it very quickly, especially when it started to become more about the business and less about the music.”

The arrival of Doug Goldstein, Guns N’ Roses’ manager, precipitated Reni’s departure shortly before the start of the tour, and the lack of creative enthusiasm on the part of Squire (“he didn’t see any future there”) also triggered his departure in 1995. For the live shows, they were replaced by two musicians who had played in Simply Red, which can be taken with considerable evidence as a betrayal of their more indie admirers. With this strange formation they landed in August 1996 at the Benicássim Festival, a concert that this columnist witnessed and that he still remembers as a clamorous nonsense, with adulterated versions of the songs, a go-go dancer on stage, and Brown with a horrible voice. At the end of that month, when they appeared at the Reading Festival, things were no better. Critic Johnny Cigarettes of the New Musical Express wrote that their rendition of I Am the Resurrection was so insufferable that it actually sounded more like eternal crucifixion. That was their last concert.

They were not the resurrection

After the break-up, Brown embarked on a solo career that was moderately well-received in the U.K., although not exactly a great success; Reni practically retired from music. Squire founded an unsuccessful group called The Seahorses, whose name, some gossips say, was an anagram of “He hates Roses.” Mani had a more focused career, joining Primal Scream at their peak. But, against all odds, in 2012 the Roses announced a reunion tour whose first two official concerts were at the Razzmatazz in Barcelona.

On their return to Benicássim, with Noel Gallagher celebrating each song on the side of the stage, they left a better taste in the mouth than the first time, although with divided opinions. “It didn’t seem so special to me. It was a more diligent concert, obviously, than the one in 1996, with better sound and a more professional attitude, but too much of it stuck to the predictable, like the classic gig of playing not to screw up, do what’s necessary, and then move on, without great showmanship,” recalls Pérez de Ziriza. There was another reunion tour, in 2016 and 2017, and the band even recorded two new singles, All For One and Beautiful Thing, which were “completely insubstantial,” according to Gendre, while Pérez de Ziriza confesses that he doesn’t even remember them.

There was a plan for a third album, which was cut short. At their final concert in Glasgow, Brown offered the audience these words: “Don’t be sad that it’s over. Be happy that it happened.” There was no announcement of the breakup and what happened between them has never been revealed because, apparently, there is an agreement between the four members not to talk about it. The fact is that the resurrection was brief and purely nostalgic, a celebration of their ephemeral moment of glory in indie rock’s past.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.