Psychoanalysis and free sex: The Sullivanians, a commune that mutated into a cult on New York’s Upper West Side

A book and a documentary reconstruct the history of an organization set up by a couple of therapists in the late 1950s. The painter Jackson Pollock and the novelist Richard Price were linked to the group, which dissolved in 1991 and once had 400 members

It was not in some desert in Oregon, nor was there a guru from afar who laid down the rules and doctrine. The Sullivanians group operated in Manhattan — the apartments and houses in which its members lived, segregated by sex, were located in just a handful of streets on the Upper West Side — and the guidelines were dictated by Saul Newton (1906-1991), trained in Chicago’s anti-fascist circles and a brigade commander on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War. The group that he created in the late 1950s with his fourth wife, Dr. Jane Pearce, advocated a radical, interventionist model of therapy: patients had to distance themselves from suffocating family ties and expand their circle of social and sexual relationships as widely as possible.

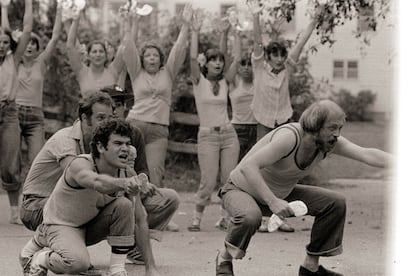

Over the years, the group became a cult, and its dissolution did not take place until 1991, the same year Newton died. “It was a radical social experiment: a 35-year attempt to reshape family, sexual, and social life in what might be America’s largest urban commune,” writes Alexander Stille in The Sullivanians: Sex, Psychotherapy and the Wild Life of an American Commune. Stille’s in-depth book and the documentary series The Fourth Wall, the first episode of which was presented at the most recent Tribeca Film Festival and directed by Luke Meyer, the son of a former member of the group, have broken the silence that has surrounded the Sullivanians. For more than three decades, the unique collective managed to operate under the radar, despite the fact that its members included well-known figures such as the painter Jackson Pollock, the dancer Lucinda Childs, and the novelist and screenwriter Richard Price.

Pollock, one of the most important figures in the abstract expressionism that shook up the art world in the United States in the 1950s, came to the Sullivanians through the legendary critic Clem Greenberg, who played a fundamental role in the growing popularity of the Sullivan Institute among artists of the time. “The group emerged in the late 1950s, a time when there was a response to the predominant culture with the beat generation, the Kinsey report on sexual conduct, or films like Rebel Without a Cause (1955),” Stille explains over the phone. But this rebellion against the established order led to an organization that maintained a tight control over the lives of its members. “One of my interviewees told me that the Stasi would have liked to have had that level of control over people in East Germany, because they controlled not only actions, but also thoughts. In therapy sessions, members confessed,” Stille says.

The group’s therapists, many of whom had been trained within the organization and had no official qualifications, determined who their patients should have sex with (the aim was to avoid “focusing” on a single partner), forced the separation of children, if they had any, and even decided which jobs they should keep. “I wanted to try to understand what led so many people to accept this. Belonging to the group offered a community, a place to live, and guilt-free sex,” explains the journalist and professor at Columbia University. His book steers clear of sensationalism. “That wouldn’t do this story justice,” he says.

At the origin of the Sullivanians were Harry Stack Sullivan and Clara Thompson, founders of the White Institute in New York, which advocated a closer approach to patients and which included Erich Fromm and Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, among others. The psychoanalyst Jane Pearce was also part of this institution, where Newton worked, although not as a therapist because she lacked a degree. “If Freud concentrated on the internal drama of each patient (the Oedipus complex, the friction between the ego and the superego), Sullivan and Thompson insisted that it was important to understand the patient in relation to other people in their life (not just the ‘family romance’ with their parents),” writes Stille.

Pearce and Newton’s Sullivan Institute went much further. “Patients were to break out of the trap of the nuclear family and monogamous marriage,” Stille notes. The radical ideas took shape in a real estate network, as the group lived in several apartments on the Upper West Side, and spent the summer in houses near Pearce and Newton’s in the Hamptons. In that early stage, the therapy encouraged creativity and experimentation for personal fulfillment. “Later, it was more about doing what suited the group, being good patients,” Stille continues. One of the therapists who eventually left, Michael Cohen, explains the shift that the therapy took from 1978 onwards: it was no longer about fostering individuality, but about getting members to comply with what the leader dictated. “If they were reluctant to put in the work or money that was demanded of them, your job was to turn them into good soldiers. Unfortunately, I was good at it,” Cohen says.

Jane Pearce would end up marginalized from the late 1970s and Newton, with his new wives — numbers five and six — would emerge as the supreme leader. They left the Hamptons for the Catskills and the group ran a theater in the East Village where the productions of their own company, The Fourth Wall, were presented. By this time, the Sullivanians fulfilled all the requirements of a cult and it was the members of the group themselves who exercised control over each other. The therapists had sexual relations with their patients, even during the therapy sessions; when one of the women wanted to be a mother, it was decided which men in the group she should sleep with so that there was no clear paternity; and as soon as the baby was a few months old, they separated them to avoid establishing “toxic” bonds.

Only the leader and his wives were allowed to continue raising their children. The lawsuits that some mothers and fathers ended up filing were what led to the story of the Sullivanians being uncovered in the late 1980s. “Saul Newton had a Stalinist component; he believed that purges were good for maintaining cohesion,” explains Stille. Richard Price told him that the reaction of the Sullivanians to the nuclear accident at Three Miles Island in 1979 (Newton ordered all members of the organization to march to Orlando) and the climate of paranoia that it unleashed made him distance himself from the group.

Stille, author of the book on Silvio Berlusconi, The Sack of Rome, and the investigation into the Italian mafia, Excellent Cadavers, says that he came across the story of the Sullivanians through friends who knew one of Newton’s sons. He thought of making a podcast but as he delved into the story he realized that it would become a book. “The people who had been part of the group were in their seventies and I think they were beginning to wonder what it had all been like. I was surprised by the things they told me, the sexual abuse they endured, being separated from their children and sent to boarding schools so they wouldn’t see them even on holidays, the therapists cornering the patients, humiliating them,” he says. In the book he details the DNA tests that some of the Sullivanians’ children decided to undergo, and what they uncovered. “The United States has a certain tradition of groups that aim to create a utopian society. Religious communities that break away from orthodoxy, groups that try to promote a new society and start from scratch, from the Shakers to New Harmony. A society of seekers,” he concludes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.