From Manahahtáanung to New York: The forgotten history of the original inhabitants of Manhattan

The Lenape people, who lived in the area before the arrival of the Dutch settlers, are at the center of an exhibition in Amsterdam. They also want an apology from the Netherlands for its colonial past

Four hundred years ago, a group of emigrants from what is now the Netherlands settled on the southern tip of the island of Manhattan. They settled there and founded New Amsterdam. In 1664, the English took possession of the settlement, which grew into New York City. For the Lenape people, the original inhabitants, colonization meant the loss of their lands and their near total disappearance: today only about 20,000 of their descendants remain. The latter are now seeking an apology and compensation from the Dutch government, supported by an exhibition at the Amsterdam Museum that illustrates a colonial period that has received less attention than other former Dutch colonies in modern-day Suriname (South America), the Caribbean and Indonesia.

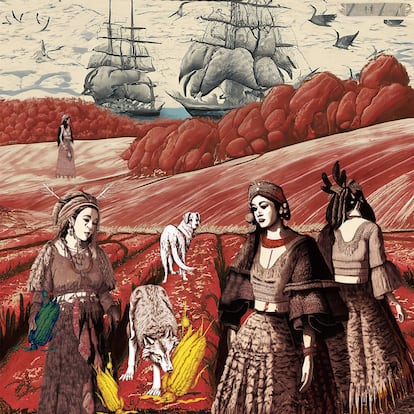

The Amsterdam Museum and the Museum of the City of New York, together with representatives of the heads of the four Lenape Nations, have joined forces to organize the exhibition, called Manahahtáanung or New Amsterdam? The Indigenous Story Behind New York. Through objects, clothing, historical documents and testimonial videos, the voice of a community is recovered “that returns 400 years later to engage in dialogue because with colonization we lost connection with our land and our culture, and language suffered,” explains Brent Stonefish, a member of the Delaware Nation, one of the four Lenape.

Stonefish has traveled to the Netherlands in search of an official apology and a form of reparation, and notes that “compensation can translate into support for language conservation and social development.” The other three branches of their people are the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation, the Ramapough Lenape Nation, and the Munsee-Delaware Nation. The effects of that process continue to this day and have generated, among other problems, poverty and a lack of self-esteem. The four Lenape nations are federally recognized by the United States government.

The exhibition is, in a way, the inverse model of cultural diplomacy used by countries to promote themselves abroad. The Lenape emphasize that they have resisted and that the museum exhibition makes it easier to talk about the past. The difficulty of this exercise lies in the fact that there are two unequal sides. On the one hand, the Dutch State, and on the other, four nations that consider themselves sovereign but lack representation in international institutions to endorse this view. “Let’s go step by step. The Netherlands’ apologies should translate into actions. Into being able to heal a community for the injustices suffered by our ancestors.”

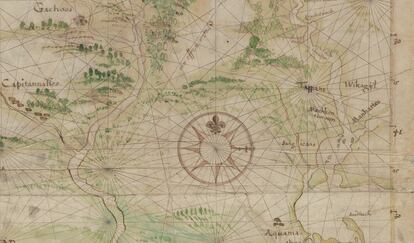

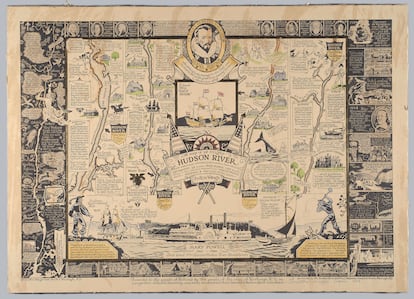

The Lenape lived on the Atlantic coast, in the northeast of what is now the United States. The men fished and hunted and the women dedicated themselves to agriculture. Their dome-shaped houses were covered with tree bark and they also built large wooden structures. In 1609, the Dutch East India Company commissioned the English explorer and navigator Henry Hudson to search for a possible northeastern passage to Asia. He had already tried to find that route on two previous occasions at the request of English merchants, so he embarked on the ship Halve Maen (“Half Moon”), of which there is a replica in the exhibition. When he had to quit the voyage due to storms, he changed course even though he had agreed with Amsterdam that he would return if he encountered problems. He started looking for a northwest passage, and what he ended up finding was the river, the bay and the strait that bear his name today. He also explored the coast of New Jersey and anchored off Manhattan Island. He also mapped the Arctic region, facilitating the polar expeditions of the 18th and 19th centuries.

In 1624, Dutch settlers, called by the Lenape “the people of salt” because they emerged from the ocean, brought there by another Dutch firm: the West India Company to populate the colony. They were about 30 Protestant families from France and what is now Belgium, persecuted for their Calvinist religious beliefs. Over time, the settlers included other Europeans, as well as enslaved or indentured people. A year later, Fort Amsterdam was built near the island of Manhattan, later converted into the city of New Amsterdam.

In the National Archives of the Netherlands there is a letter dated November 5, 1626 and written by Pieter Schaghen, which reported the purchase of the island of Manhattan from the natives. “Dutch merchants bought it for 60 guilders,” the note reads. At the current exchange rate it would be about $24, according to archival sources, and there arose the legend that Manhattan was purchased at that price. The Lenape were unaware of the land trade, and what possessing land meant for a European; for the indigenous community it must have meant nothing more than the granting of a temporary use permit. They did not renounce living in their ancestral territory, but they were forcibly removed from their home.

“They massacred us. Thinking that our ancestors sold our land for trinkets like this is a way of saying that they were primitive, uncivilized and unintelligent. Recognizing that this was a mistake [on the part of the Netherlands] would allow our ancestors to rest,” says Stonefish. He also says that if there had been a clear sales agreement, a wampum would have been composed. It is a string of beads that represents a treaty. Two ribbons have been placed in one of the display cases with the intention of completing it as a symbol of a new understanding.

A wall was built around New Amsterdam to keep out the natives and also the English. Over time, the wall became Wall Street, and Manahahtáanung became Manhattan. Part of the Lenape trade route (Wickquasgeck) became Brede weg and later Broadway in English, according to the National Museum of the American Indian, part of the Smithsonian Institution.

The colonial situation changed in March 1664 when King Charles II of England gave the lands to his brother, the Duke of York, at a time when peace reigned between the two countries. They had been at war before and they would fight again later. When several English ships arrived in the port of New Amsterdam that same year, Peter Stuyvesant, the colony’s director general, surrendered and handed it over. In 1667, by virtue of the Treaty of Breda, the Dutch renounced New Amsterdam in exchange for Suriname, which was in English hands. From then on, New Amsterdam was renamed New York.

The Museum of the City of New York will present a follow-up exhibition in 2025. According to Monxo López, one of its curators, “there was a cultural aspect and a political aspect because the Lenape told us that they were seeking to establish diplomatic relations with the Netherlands.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.