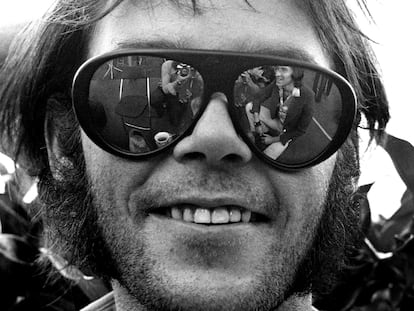

A failed iPod rival, divorce, model trains and several albums: The restless golden years of Neil Young

Just shy of his 80th birthday, the Canadian singer-songwriter continues to make headlines thanks to a prolific musical career — as well as his offbeat business ventures

On the brink of turning 80, Neil Young is still making headlines. For example, September 24 became a banner date for his loyal fans when he finally played Hey Babe, a song off his 1977 album American Stars ‘N Bars, for the first time in a live concert. A few nights before, he debuted his new band (The Chrome Hearts, which features Micah Nelson) during one of his recurring performances at Farm Aid Festival, an annual event he organizes to provide financial support to U.S. small farmers. September 6 was also a big day for Young, marking the presentation of the third volume of his monumental musical archives.

In contrast with other legends from his day — with the exception of his friends Bob Dylan, who is embarking on his Neverending tour, and Wille Nelson, who dropped his 154th album in November — Young never rests. Moreover, nearly everything the Canadian does resonates with significance, commanding our full attention.

“If I think of a song or a project to put out, I have to do it immediately. As soon as I have an idea, I get into it and forget everything else,” Young told interviewer Zach Sang a year ago. On other occasions, he’s joked that if he were an airplane pilot, he’d crash immediately, “because I’d take my hands off the controls as soon as a melody appeared.”

Given the facts (like so many legends, he has composed songs while driving, as goes the origin story of Like a Hurricane), that artful disaster is easy to imagine. Indeed, it’s difficult for even Young’s most dedicated fans to keep up with the pace at which he releases new work. In the last five years alone, he has dropped three studio albums (Colorado, Barn and World Record) with his classic band Crazy Horse, plus All Roads Lead Home with Molina, Talbot, Lofgren & Young; not to mention four live albums and three previously unreleased “lost albums” (Chrome Dreams, Toast, which recorded in 2001, and Homegrown, which features songs from Young’s glory years of 1974 and 1975.)

Of course, Young has famously stayed busy declassifying material from his archives, putting them out piece by piece in enormous box sets. The third, recently released installment hails from his controversial period between 1976 and 1987 and includes 17 CDs and five Blu-Rays (nearly 100 hours of music, obsessively packaged alongside commentary from its creator). To say such an effort is best suited for hardcore fans is an understatement.

And that’s just the music. In another recent interview, in which Dan Rather asked about Young’s famous lyric “it’s better to burn out than to fade away,” the singer-songwriter said that the words only make sense, “for rock ‘n’ roll, if that’s all you are and that’s all you want to do, exploding is not bad. But there’s a lot more to life than just rock ‘n’ roll.” Namely, “Children, family, relationships, nature, beauty — it has all these other things that rock ‘n’ roll is part of, but rock ‘n’ roll is its own thing, it’s an animal all to itself.”

As proven by his own trajectory, full of confrontations with corporations, environmental activism, controversial relationships with politicians, more and less successful technological forays, prosperous businesses, failed businesses, devotion to fatherhood and all kinds of existential vicissitudes, there’s life beyond rock for even the “godfather of grunge.”

Force of nature

Only his best friends speak poorly of Young. Take for example, David Crosby, who died in January 2023 but took advantage of his last interviews to opine that “Neil is probably the most selfish person” he’d ever met. Then there was the writer Jimmy McDonough, author of Shakey, an in-depth biography that was initially authorized and then unauthorized and is considered a stellar example of its genre. Nowadays, the writer refuses to comment on the musician. But he did at one point recall how, while he was writing the book, everyone who depended on Young “were fearful. It always is that way when you have a celebrity who pays people and you want to talk to them,” he said.

It’s often said that Brian Epstein was the fifth Beatle, that Mick Jagger and Keith Richards wouldn’t have been anything if they hadn’t had one another, but it’s difficult to say who has been Young’s righthand man. He periodically fell out with his collaborators, the legendary supergroup Crosby, Stills and Nash (his only friendship that has never faltered was that with Stephen Stills), as well as with the members of Crazy Horse. Among them, even Frank Sampedro seemed destined to disappear and reappear in Young’s orbit, only truly shining when he was near the guru himself.

Figures like producer David Briggs and manager Elliott Roberts passed away years ago, yet their absence had little noticeable impact on Young’s career. Even after his divorce from his wife, Peggy Young, in 2014 — who he had been married to for 36 years and who passed away in 2019 — his legendary productivity showed no signs of waning.

It could be that the Old Man singer’s ability to ceaselessly work alone is due at least in part to a tumultuous temperament (“it’s hard to disagree with me,” he admitted to Zach Sang). But perhaps that has also prevented him from ever breaking with his compromise to truth and honestly in music. It’s no coincidence that one of the metaphors most frequently employed by critics for Young’s work is that of a natural phenomenon, as if his voice and his guitar’s distortion came from some superhuman force.

“But we’re not talking about a hurricane, or a flood, or a plague,” explains Luis Boullosa, music critic and leader of the band God y las Hienas Telepáticas. “Really, we’re talking about a venerable oak tree, approachable, nearly one with the men who have watched him grow since they were children. As a mythological figure, Young embodies not the common man, but the group of common men who know how to resist adversity and distinguish, through instinct and nobility, between good and evil.”

Pablo und Destruktion, one of the Spanish musicians in whom the Canadian artist’s influence is most evident, seconds the words of Boullosa, adding: “He lived through all the folk revivals, starting at the beginning of the 1970s and every one since, given that they come around more or less every 15 years. He was there through thick and thin, and was always able to revitalize his connection with truth and the land, with the song as something confessional. He is a paisano — which here in Asturias means, as in Castilian Spanish, a native to the area, but goes beyond that. It is like being a gentleman of the people, something akin to a nobleman. And that has really impacted me, it inspires me a lot in both live performances and in recordings.”

Everything besides rock: parallel adventures and businesses

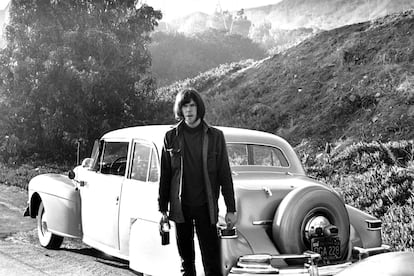

In 2014, Young joined stars Elton John, Emmylou Harris, Dave Grohl and Bruce Springsteen to make a promotional video for PONO, a high-quality digital media player that he had developed and funded in the hopes of it competing with the iPod. But despite its famous backers, the product never took off. PONO is just one of the latest examples of technological projects on which Young has embarked and which, according to McDonough in Shakey, have filled up his Broken Arrow ranch with eccentric engineers, bearded automotive restorers and tech company representatives.

Shortly before launching PONO, Young had focused all his energies on the LincVolt project. LincVolt is a Lincoln Continental, a classic car from 1959, that the rock star made into a hybrid vehicle around 2010. Young’s commitment to the cause was such that he traveled the United States detailing the charms of electric motors and biofuels. He was even compelled to offer fans, according to forums like Reddit, a chance to meet him in a much more intimate way than his concerts had afforded over the years. At the 2013 edition of SEMA (a car conference held in Las Vegas), he spent hours talking about the upsides of fuel cells and batteries, answering all manners of questions from other motoring enthusiasts.

Are these the offbeat endeavors of a millionaire still heavily influenced by the counterculture of those long-ago years when everything seemed possible? Or are they the product of a committed activist determined to change the world in ways that go far beyond the bounds of art? The answer is, probably both. At least, in recent years, Young has managed to bring issues that Americans (particularly his own fans) are loathe to address into public discourse, from fuel economy to climate change, the harmful effects of genetically modified crops or — less urgently, perhaps, but surely closer to his established wheelhouse — the poor audio quality offered by streaming platforms.

There’s no doubt that aside from music and environmentalism, model trains have emerged as one of Young’s primary passions. The singer managed to buy 20% of Lionel, the sector’s most prestigious company and, in collaboration with technicians (supposedly in the 1990s, at the end of each concert, he’d dash to meet up with employees of the model train firm), he developed a multitude of models and apparatuses that helped to strengthen his relationship with his son Ben, who has cerebral palsy.

His drive to better communicate with Ben also brought him to co-found the Bridge School in 1987 with Peggy. Until 2016, the institution was funded by benefit concerts in which not only Young performed, but also Tom Petty, Paul McCartney, Sonic Youth and R.E.M. (Young, of course, has a stellar Rolodex.) The school continues to employ cutting-edge technology to serve students with complex needs.

What would Neil Young do?

In 2009, the Primavera Sound festival paused the rest of its programming so that all attendees could focus on the main stage, where Young was set to perform. No one, not even the EDM heads, complained. Young has long been an institution, perhaps the only performer around which a certain consensus has coalesced (not even Dylan has managed such a feat).

The Canadian manages to convey a seldom-seen authenticity in his work and a commitment to his causes, and his labors go far beyond his personal brand. Pablo und Destruktion explains it like this: “What happens to people who follow their own path? They are on a traditional timeline, and a traditional timeline is seldom linear. There is no more fashion, because honesty is not progressive or decadent; it is not left-wing, it is not right-wing; it is not from the 1960s or the 2000s… it’s just honesty. And these artists, who have a touch of prophet in them, know how to use that kind of timeline as a source of eternal youth. They are always where they have to be and they are always what they are.”

One must wonder: in 2024, is the cult of Neil Young still justified? Do all his album drops, projects and battles, his obsession with sound quality and crusade against Monsanto, make sense?

Boullosa provides one take: “Everything he does can be argued against. But to do so, you have to make a petty descent into the biographical details of a man who is doubtlessly more complicated than he seems. Or have a bone to pick with some old, inconsequential record of his. Or think that his commercial chimeras are absurd. But whether the actual man of today resembles the leafy tree he became decades ago, that’s none of our business. And it doesn’t affect the larger, spiritual truth: at the end of the day, when a problem comes up, ‘what would Neil Young do?’ is not the worst question to ask.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.