Daryl Hannah, the actress who has never held back: ‘I’ve been hearing that I’m too old for certain roles since I was 30’

Forty years after ‘Splash’, the film that made her a star, the actress has tasted success and failure, harassment from the press, the violence of Harvey Weinstein and decided that a movie icon can do much more than just act

Forty years ago, the release of Splash, a romantic comedy update of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, introduced the world to a fascinating creature: Daryl Hannah, a tall, statuesque blonde with blue eyes who led to an army of girls now in their forties named Madison, like the film’s protagonist. A role previously rejected by Sharon Stone, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Melanie Griffith served to consolidate her hitherto stop-start career. What few could have imagined was that this sudden stardom, which would have made any emerging actress happy, was a real ordeal for her. The whole film had held a certain nightmarish air. “I was very world-traveled, but very sheltered at the same time,” she told People. “I hadn’t really had a boyfriend yet… So I was incredibly anxious about any nudity.”

She was also terrified of the kissing sequence. “Once you do it once, then it’s easier to get through the next time. But that first time, when you don’t know somebody and you have to kiss them, is so embarrassing. At least for me, it was.” It is a surprising detail in the biography of an unconventional woman who in 2024 is making more headlines for her fervent environmental activism than for her appearances on the red carpet. She continues to work, although no one pays much attention to her now. And that doesn’t seem to bother her at all.

The turning point in Hannah’s life came after her parents separated. She was seven years old. She sought “refuge in the safety of an imaginary world” and her self-absorbed attitude alerted her teachers, who suggested her mother put her in an institutional setting. “I think I was simply uncommunicative and lived in the clouds. Then, as a teenager, I was diagnosed with mild Asperger’s syndrome. Now I’m still weird, but I keep it to myself,” she told EL PAÍS during one of her visits to Spain. Instead of putting her in an institution, her mother took her to live in the Bahamas for an indefinite period so she could do whatever she wanted. They did not return home until she felt well again, one of the advantages of being immensely rich. After her parents’ divorce, her mother had married Jerrold Wexler, a multimillionaire businessman.

Hannah wasn’t a great student. She excelled in sports thanks to an athletic physique that in turn made her self-conscious. She liked ballet and theater and knew that her calling was film. She had fallen in love with acting as a child, when her insomnia led her to discover classic cinema. As soon as she finished high school, she moved to Los Angeles to try to break into the industry. It didn’t hurt that her mother’s new husband’s brother was Haskell Wexler, director of photography for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? But Hannah didn’t need much help: the physique that made her self-conscious also caught the eye of agents and producers.

She was a new face, and “one thing they do well in Los Angeles is smell fresh meat,” she declared. Her looks condemned her to cliché, to being the dumb blonde serving the male lead. “She’s capable of doing much better parts than she’s gotten,” her uncle proudly observed. “Unfortunately, she’s wrapped up in the kind of body and face that prevents people from seeing beyond that.” The Guardian defined her as “a Valkyrie who behaves like a faun,” a good introduction to her first major role, as Pris, “the basic pleasure model” replicant in Blade Runner (1982).

Hannah is one of the most fascinating presences in a hypnotic film that was not overly appreciated at the time. But it was by her, as she saw her dream coming true. That was exactly what she was looking for. “When I did Blade Runner, I was completely transported to another world. The whole thing was perfect. It was just what I wanted. I wanted to become another person. I wanted to live in another reality,” she said.

Splash revealed to her the negative side of the profession. “I always loved the process, but I was very uncomfortable with the other aspects of the job, the publicity and all that stuff,” she told The Guardian. She was by then aware that the industry did not resemble the glamor of classic cinema that had enamored her in her childhood. “I didn’t realize that, because I was a self-conscious, picked-on kid, when people were looking at me, I’d feel they were making fun of me.” The old ghosts returned; she felt like she was back at school. “I knew that people were looking at me because I looked weird.”

The success of Splash pigeonholed her as “a particularly ignorant male fantasy protagonist: the clumsy, innocent girl in a woman’s body.” She was aware of it and accepted it. “Every 20-year-old actress is installed in that way. It’s a male-dominated industry. It’s just a bunch of guys saying: ‘Let’s make the girl younger, and sexy, and hot.’ So, yeah, of course it’s exploitative. And that’s unfortunate because it has the potential to be really transformative in expressing the human condition.”

Some of those roles based solely on her looks were resounding failures, such as The Clan of the Cave Bear (1986), At Play in the Fields of the Lord (1991) or Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992). She received a Razzie for her performance in Wall Street (1987), Oliver Stone’s X-ray of 1980s greed. She also had some discreet successes: she was charming in Roxanne (1987), a modern version of Cyrano de Bergerac, and as the third wheel in the comedy Legal Eagles (1986) alongside Robert Redford and Debra Winger, although again she played a sexualized child-woman.

Success and the predator

She made up for the Razzie in the choral and tear-jerking Steel Magnolias (1989), but it would take almost 15 years until she hit the big time again. She did so, like so many forgotten stars, thanks to Quentin Tarantino seeing the dark side of a seemingly celestial creature and giving her a crucial role in the two instalments of Kill Bill (2003 and 2004).

“I was doing a play in London and he just showed up backstage one night after the play. He’d flown in town just to see the play and was leaving the next morning. All he told me about it was that he was writing something with me in mind,” she said. “I’ve always been a big fan of his and admired his work, and so I was nothing but excited all the way through. I even worked as a crewmember at the end of the film when I finished shooting.” She excelled in the role of Elle Driver, the most lethal and amoral of Bill’s henchmen. And it generated another iconic sequence: her walk through the hospital whistling Bernard Hermann’s music for Twisted Nerve.

Kill Bill marked a turning point, but not everything about it was positive. She is sure that Harvey Weinstein had something to do with the slowdown in her career. The first time they met, he praised her work and asked for her phone number. Hannah did not know about his reputation and thought it a was normal request, but it did not seem normal when the producer showed up at her hotel and banged on her door. She escaped through another door and spent the night in her makeup artist’s room. Their paths crossed again during the promotion of the second part of Kill Bill, but this time the producer did not bang on the door: he used his key to open it to the surprise of a terrified Hannah, who fortunately was accompanied.

“He just burst in like a raging bull. And I know with every fibre of my being that if my male makeup artist was not in that room, things would not have gone well. It was scary,” she confessed to Ronan Farrow in one of the key articles that helped to unmask the producer. In the third meeting she couldn’t avoid him: Weinstein demanded that she attend a promotional party downstairs at the same hotel, but when she arrived she discovered that the event didn’t exist, the room was empty; there was only Weinstein and her. “Are your tits real?” he asked her. Weinstein asked her to let him touch them, or at least see them. “And I said, ‘Fuck off, Harvey,’” she told Farrow. The following morning, Miramax’s private plane left without her and her flights to Cannes were cancelled.

Unlike some of Weinstein’s victims, Hannah did not remain silent. “I called all the powers that be and told them what had happened.” It only served to make her realize the impunity with which the head of Miramax operated, and how fragile her position was. “I think that it doesn’t matter if you’re a well-known actress, it doesn’t matter if you’re 20 or if you’re 40, it doesn’t matter if you report or if you don’t, because we are not believed. We are more than not believed — we are berated and criticized and blamed.” This chapter of her biography helps to explain why, other than her role in Sense8, the fascinating fiction by the Wachowskis for Netflix, she did not participate in any other major production after her success in Kill Bill.

She hasn’t stopped working, even behind the camera. In 2018, she wrote and directed Paradox, a musical starring her husband, rocker Neil Young, with whom she also worked on the documentary A Band, A Brotherhood, A Barn. Her relationship with the Canadian musician has developed outside the media spotlight. It only became public knowledge that they had married in 2018 due to the indiscretion of a friend. Hannah’s tempestuous, decade-long relationship with musician Jackson Browne had ended in 1992 amid allegations of domestic abuse.

John-John arrives

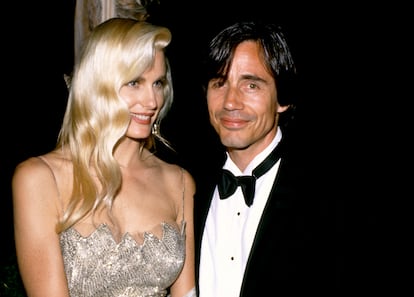

Hannah and John-John Kennedy had been friends since their teens, when they both spent the summer in St. Martin in the Caribbean, and they met again at the wedding of Herbert Ross — who was directing her in Steel Magnolias at the time — and Kennedy’s aunt, Lee Radziwill, Jackie Kennedy’s sister (and one of Capote’s “swans”). That meeting served as the spark, but at the time they were both engaged. When they finally started dating, they became the paparazzi’s favourite couple. They dazzled everyone, except the groom’s mother, who opposed their relationship as she had previously opposed her son’s romances with Madonna and Sarah Jessica Parker.

Hannah has always been aware that others think she is a bit eccentric and she does not strive to do what is expected of a movie star. Her work as an activist has long taken precedence over her acting career. She has even been jailed for it: in 2006 for chaining herself to a walnut tree in defense of an organic farm in South Los Angeles; three years later for protesting against the exploitation of the Appalachian peaks for coal; and in 2011, for demonstrating in front of the White House against the construction of the Keystone XL oil pipeline.

“Nobody likes going to prison,” she told EL PAÍS in 2012, “or being handcuffed, but sometimes it is necessary to send a message.” Hannah does not live in a mansion in the Hollywood Hills. “I don’t want bigger houses and cars.” She talks about sustainability, and she leads by example. She gets her water and electricity from her own sources. Her houses run on solar power, her toilets are compostable, and her cars use leftover oil from fast food restaurants as fuel. She grows her own food and sells the surplus at a farmers’ market; she raises bees, knits, and takes care of every abandoned animal that ends up on her farm: cows, horses, alpacas, chickens, dogs, cats… which she proudly displays on her social networks, more typical of the owner of an animal sanctuary than a star.

Unlike other celebrities, she doesn’t plan to get involved in politics, but she doesn’t live in isolation from it either. “While we live in deception, the penitentiary system, health care, water, are being privatized. As a human being, my commitment is to be an informed citizen and use my voice to get other people involved. Real change starts from below, not from above.”

And she continues to work, even though some people think her time has passed. “I’ve been hearing that I’m too old for certain roles since I was 30, and I’ve never stopped working. I feel young, so I don’t even think about it: only when I see some comment on the internet about how bad this or that touch-up has turned out. Why do they think I’ve had surgery, if I’m full of wrinkles?”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.

More information

Archived In

Últimas noticias

Most viewed

- Sinaloa Cartel war is taking its toll on Los Chapitos

- Oona Chaplin: ‘I told James Cameron that I was living in a treehouse and starting a permaculture project with a friend’

- Reinhard Genzel, Nobel laureate in physics: ‘One-minute videos will never give you the truth’

- Why the price of coffee has skyrocketed: from Brazilian plantations to specialty coffee houses

- Silver prices are going crazy: This is what’s fueling the rally