Greek mythology and oversized egos: The Genesis album that ended progressive rock

It’s been 50 years since the release of ‘The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway’, the band’s last work with Peter Gabriel. For many experts, it was also the last record of a genre that continues to inspire fans today

On November 25, 1974, while on tour in Cleveland, Peter Gabriel told his bandmates that he would be leaving Genesis at the end of the tour. Their ambitious double album The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway had only been in stores for three days, and the decision was kept secret. When Gabriel announced it in a press release in August 1975, he claimed that he had become disillusioned with the record industry and needed to spend more time with his family.

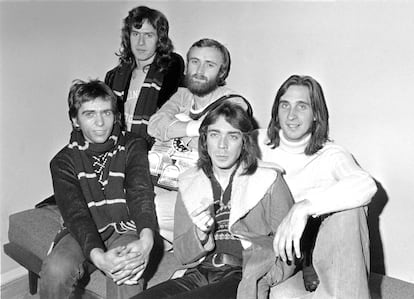

But the real reasons were more to do with professional jealousy. Gabriel — who was also the group’s lyricist and musical ideologist — was increasingly going it alone and attracting all the attention, while the contributions of Steve Hackett (guitar), Mike Rutherford (bass), Tony Banks (keyboards) and Phil Collins (drums) were receiving less public attention. So the band welcomed the vocalist’s departure with more of a sense of relief than of doom.

Formed in 1969, Genesis had been releasing an album every year, gaining increasing prestige that turned them into one of biggest names in progressive or symphonic rock. Their fifth album, Selling England By The Pound (1973), was their biggest critical and commercial success. The band — which formed at the elite Charterhouse School in the British county of Surrey — seemed to be unstoppable. But when they decided to record their next album, problems began to surface.

Rutherford proposed composing a conceptual album based on Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, but Gabriel replied that it was too cheesy and they dismissed the idea. The vocalist — already hugely popular for his eccentric ideas and stage theatrics —struck back with the surreal tale The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway, which was set in New York and starred a Puerto Rican boy named Rael. For the first (and last) time in Genesis’ career, it was Gabriel who wrote all the lyrics, while the rest of the band did the composing, which widened the distance between them.

“The lyrics are influenced by biblical stories, Greek and Latin mythology, the works of Carl Gustav Jung in psychology, Timothy Leary’s Tibetan Book of the Dead, the tradition of English religious epics such as John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress… All of these readings by Peter Gabriel create a dizzying level of intertextuality, without which it is difficult to interpret the long initiatory quest of Rael, a character completely overwhelmed by events,” notes French musicologist Marion Brachet, an expert on Genesis and progressive rock.

The fact that Gabriel alone created the album’s concept led to it being considered a de facto solo album, with his bandmates merely supporting instrumentalists. There were also some contributions from Brian Eno, who is credited for his “enosifications.” Recording the album was a challenge. The process began at Headley Grange, a former Victorian workhouse for the poor where Led Zeppelin used to record. But Genesis discovered that the place was infested with rats, with the floor covered in feces.

The band finished recording at a mansion in south-west Wales, where they brought a mobile studio. This allowed them, for example, to record some of Gabriel’s vocals in a cow barn two miles from the site. In between, all the members of the group had their own personal or family problems to deal with, and to add even more tension, the vocalist was absent for stints because he was working on a film script with filmmaker William Friedkin, although the project never came to fruition.

When the album was released on November 22, 1974, it was received with mixed opinions, although it grew a cult following over the years and, today, many consider it the pinnacle of Genesis. According to Javier de Diego Romero, author of the book Peter Gabriel: A Musical Explorer and His Time, “it is a fascinating work because it is located on the border between the past and present represented by progressive rock and the future that punk would bring with it. We are faced with a conceptual album, as was de rigueur at the time, but made up mostly of relatively short and direct songs. Musically, I consider it one of the great double albums in the history of rock. Not a single one of its 94 minutes is superfluous, it is a consistently brilliant album.”

A multimedia concert in Franco’s Spain

Even more revolutionary than the album was the accompanying tour, as Marion Brachet rightly points out. “The album was played in its entirety and in order. This practice was new and quite demanding, especially for the American public, who were not yet familiar with the work because it had not yet been released at the start of the tour,” she explains.

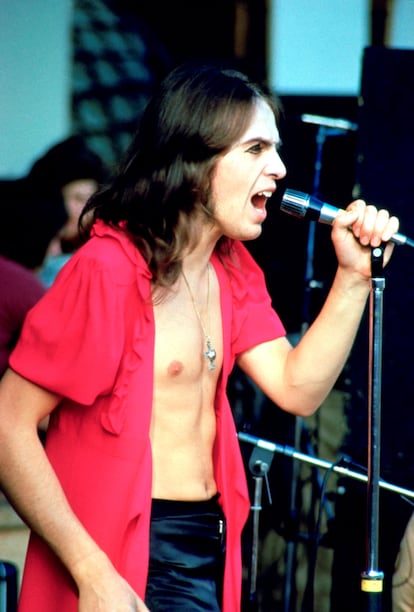

“The set design was also complex: numerous images were projected on the back of the stage to accompany the development of the story [around 1,500 slides on three screens]. This was complemented by stage settings and costumes worn by Peter Gabriel,” she continues. “The initiative to bring a multimedia creation into the concert hall, with the entire album, laid the first foundations for a tradition that is now well established in rock music, which consists of giving each tour for the album in question a strong and unique identity.”

The band played 104 concerts over six months. In February 1975, they landed in Europe and played in three Spanish cities, when the country was still under the Francisco Franco dictatorship: Badalona (Juventut Pavilion, on March 9 and 10), Madrid (Real Madrid Pavilion, the following day) and San Sebastián (on May 18, at the Anoeta Velodrome).

This last concert was attended by a 14-year-old called Ricardo Aldarondo, who would later become a musician and journalist. “They placed chairs on the track of the Velodrome, so everyone was seated, like in a theater,” he explains. “But it was not full of chairs, it was not a massive concert, back then, that was impossible, it was not the custom. I don’t know how many people attended, but from my memory of the venue I don’t think there were more than 3,000 or 4,000 people.”

It was Gabriel’s last concert with the band in Spain. After that, he only stopped in Paris, Cambrai and Besançon, where he announced his departure by beginning the concert with the oboe solo of The Last Post, a famous British call played at military funerals.

“The whole concert was a constant wonder because of the staging, the combination of slides on three backdrop screens, the strange characters that Peter Gabriel played, the stage elements and the lighting effects, really something never seen before,” recalls Aldarondo. “Now it may seem naïve, but at that time, there had never been anything so advanced and so well conceived from start to finish.”

As for the stage charisma of Gabriel, Aldarondo says: “He was totally fascinating, because of the expressiveness of his gestures, the way he moved on stage, the way the lights enhanced his appearances and disappearances, and the drama of his moments.” The journalists also mentions the band’s “British and surrealist humor,” with the show including strange creatures, laser lighting and a spinning cone-like structure.

The swan song of progressive rock

Peter Gabriel’s departure from Genesis was not the catastrophe that was expected. The vocalist began a solo career in 1977, and Genesis continued onward, in a more pop direction, with Phil Collins assuming the role of singer. “It was a strange case, nobody expected it, but both sides won,” says De Diego. “Gabriel, on his own, had more freedom to explore his ideas, to display his creativity, and he adapted amazingly well to the new musical order that arose after the punk explosion. And Genesis enjoyed commercial success that was considerably greater than they had had with Peter. It must be taken into account that all the members of the group were great composers, they did not depend on Gabriel and, therefore, did not suffer from his departure; and Phil Collins was a great singer. The only aspect in which they lost was the live performance: Gabriel’s captivating theatricality was irreplaceable,” says the critic.

According to Marion Bachet, “Peter Gabriel’s departure from Genesis can be interpreted as a swan song for the golden age of progressive rock.”

For Ricardo Aldarondo, “The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway marks the peak of what the musical ambition of symphonic rock could give.” He says that the rise of punk — which went back to the basics — clashed with the excess of symphonic rock. “But it was precisely Robert Fripp [from King Crimson], Peter Gabriel and Peter Hammill, with Van Der Graaf Generator, who knew how to break these constraints. And each in their own way led the new avant-garde in parallel to punk during the 1980s. In fact, they formed the most sensible, inventive and visionary wing of all that.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.