Men, guns and penises: How the Western film genre became the definition of masculinity

The genre of manhood par excellence has also been the canvas on which to reflect all the types of men that exist and all the relationships that can be established between them. This has been done in an increasingly free and explicit way in recent years

Back in the 20th century, a lot of movies were shown on television. Some — known as Western films — were labelled as products for male consumption. Movies by men and for men (like almost all historical or adventure films), where women had domestic or romantic roles in the background. The leading roles were reserved for the heroes. And between the hero and the woman was the villain, of course, who also symbolized frontier masculinity. The action typically took place in a dangerous territory — in the process of being “civilized” — inhabited by Indigenous people, who were usually depicted as monsters.

This is a rather condescending take on a genre that — having always had relative freedom to be explicit — has managed to offer profound reflections. However, the stereotype still exists to some extent, as the genre evolves with the times and maintains solid health.

It’s interesting that a genre so specifically located in time and space — the settler frontier of the colonial-era United States — has exceeded its own limits in such a disproportionate way. It’s not just that the Western has been mixed with so many genres that the meaning of the term has disintegrated… it’s that Westerns are now shot and written all over the world. There have been, for instance, the spaghetti and chorizo Westerns that are respectively churned out by the Italians and the Spaniards. In Spain in particular, thousands of Western novels were read for years by the majority of the population. And, in recent years, several Spanish Western films — such as Strange Way of Life (2023), by Pedro Almodóvar — have been released to international acclaim, starring actors such as Ethan Hawke and Pedro Pascal.

Beyond the indisputable colonizing power of American culture, the Western seems to have transcended the category of mythological space. Naturally, such an exuberant genre has also transcended its own rules and prejudices, snatching the white man’s point of view to pay attention — either explicitly or clandestinely — to the conflicts of women, Natives and even “the other white man.” That is to say, villains and LGBTQ+ people. But let’s start at the beginning.

Dorothy M. Johnson (1905-1984) — the great dame of American Western fiction — was a writer who dedicated her work to sharing the spotlight equally among all the inhabitants of the territory. In her stories, women, Indigenous people — and even Indigenous women — are as much protagonists as the white man. Her chronicles and stories are chillingly good, exciting and morally complex. When she was asked what a woman was doing writing Westerns, she replied that the inclination to write about the frontier was not a sex-linked skill, like the ability to grow chest hair. And, when she herself asked if a Western could star a man who was neither brave nor knew how to shoot, she wrote a short story called The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1953), which gives us a measure of both her talent and her importance. Isn’t Johnson’s experiment — that of putting the spotlight on the coward — yet another reflection on masculinities?

This is easier to explain through the film made by John Ford — an Irishman (curiously) and one of the masters of the Western film genre — based on Johnson’s story. Two very different men star in the movie: John Wayne and James Stewart. You just have to look at them: hard masculinity and soft masculinity, embodied.

Johnson depicts the classic hero of the western: Wayne and his monolithic masculinity, with his pistol on his hip and his virile sobriety. He never takes off his boots and maintains an impenetrable gaze at all times. Meanwhile, the director contrasts this with Stewart’s slender body and his trembling hands that don’t adapt to the weapon. He also dares to question official accounts of the Wild West, to suggest that history may not be as we have been told and to warn about the dangers of trusting appearances when it comes to masculinity.

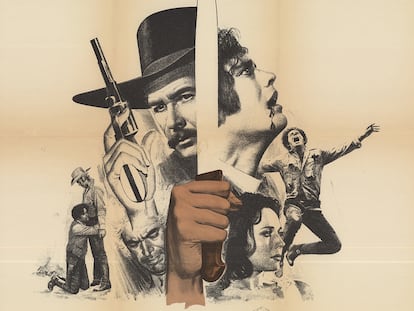

The classic, gentrifying Western often tried to whitewash the origins of a nation recently constructed through genocide (at least on screen, not so much on the page). Set in a place where women are scarce, it also ended up becoming — in spite of itself — a reflection on what it means to be a man, as happens in the prison, sailor, or gangster genres. Essayist Juan Dos Ramos and illustrator Alex Tarazón use Spanish-language graphic novels to explain how the regular consumer of film noir has traditionally been unable to see the obvious signs of LGBTQ+ identities among the overwhelming presence of extravagant masculinity, something so common in the gangster genre. Oftentimes, this “eccentricity” was nothing more than a way of camouflaging non-heterosexual identities. The same has probably happened with the Western film genre, a direct precursor to gangster cinema. It was difficult to avoid in a world where men spend their days measuring their phallic symbols in duels…

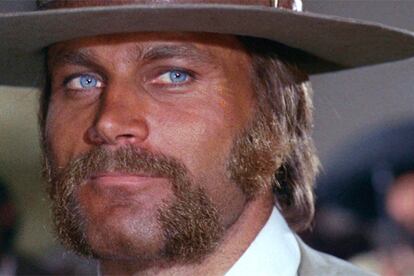

As a reaction to the canonical Western and its attachment to the official account of events, the so-called “spaghetti Western” emerged, incorporating all the messy things that happened on the frontier. Sergio Leone and Ennio Morricone — both Italians — made five Westerns together that are legendary. Their nameless character — played by Clint Eastwood — undergoes a journey that becomes less and less playful and more melancholic, making for a Western that finds the epic more in pettiness than in grandeur. The subgenre of spaghetti Westerns is a kind of feast for vultures: the characters lick their wounds, lamenting wasted opportunities. In the films, it’s evident that the New World will make exactly the same mistakes as old Europe.

Leone and Morricone also revolutionized the Western through their music — which played over the landscapes of Spain’s Almería, Granada and Burgos — and through their rhythm and close-ups, which turned the faces into landscapes. The faces in their films challenge each other: they’re scorched by the sun, their eyes are half-closed. There are no heroes in these settings. Rather, there are convicts, ruffians, peasants, opportunists, gunmen, bandits, chieftains, bounty hunters, miners, settlers, missionaries, deserters, desperados, soldiers who have lost faith, the good, the bad and the ugly… indeed, a formidable collection of scoundrels covered in filth, which constitutes a true bestiary of masculinities.

But Leone’s case isn’t representative of all spaghetti Westerns, which are generally overblown, low-budget productions. We already know that the relationship between budgets and the grotesque is inversely proportional… and we know that the grotesque is fertile ground for embodying projections of the subconscious and representing what cannot be said. For instance, in Cursed Gold (1967) — directed by legendary Italian director Giulio Questi — a gang of outlaws give themselves over to a party every night, unleashed in joint drunkenness. Naturally, we cannot see the heart of the party, but the sunrise — with the bodies piled up on the stage, reminiscent of The Damned (1969) by Luchino Visconti — couldn’t be more eloquent.

In The Marked (1971) — a Mexican western, directed by Alberto Mariscal — the outlaw villains are two gay men who are in a relationship. They’re not effeminate… and they also happen to be father and son. The use of incest and absurdity are employed as resources to turn the villains into deviants, so that the viewer welcome the extreme punishment that they receive. In Requiescant (1967) — directed by Carlos Lizzani, where Pasolini himself appears playing a revolutionary priest — the Draculian chieftain is in love with the most handsome and blonde gunman in town. And, in The Mercenary (1968) — directed by Sergio Corbucci — Franco Nero, the hero with full lips, decides to humiliate an evil Jack Palance by stripping him naked in the middle of the bullring and painting his face like a clown (Palance, by the way, is in admirable physical shape).

The archetype of the angel-faced gunslinger — whose beauty makes the women around him tremble — is a constant in spaghetti Westerns, probably encouraged by the need to take advantage of the excesses of leading men in Italian cinema.

But scoundrels, wretches, villains and dandies aside, the explicit presence of LGBTQ+ characters — without excuses — is beginning to become normal in the genre. And some of the most popular examples — despite being considered Westerns — are set in the 20th century. This is the case of The Power of the Dog (2021) — directed by Jane Campion of New Zealand, based on the 1967 novel by Thomas Savage — where the protagonists travel by car, even though they live on a ranch. And of course, there’s Brokeback Mountain (a story by Annie Proulx published in 1997, adapted into a film by Ang Lee in 2005), which depicts a relationship between two American cowboys. However, films such as Midnight Cowboy (1969) and The Dallas Buyers Club (2013) are excluded from the category of Westerns, because despite the cowboy protagonists, they take place in urban environments. As Willie Nelson and Orville Peck sing, cowboys often flirt with each other, without anyone finding out.

The books depicting the Wild West have been much more daring than the movies. The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon (1991) is a novel written by Tom Spambauer, a gay man who grew up on his parents’ farm next to an Indigenous reservation. He moved to New York City just in time to encounter the AIDS crisis. It’s one of those novels that — if you’re lucky enough to come across it in your adolescence — leaves you stunned. It tells the story of an Indigenous man raised in a brothel in Idaho, during the gold rush. Naturally, he’s dedicated to the oldest profession in the world. The novel has a tremendous erotic charge and narrates how — among many other things — that, in the Wild West, nobody was surprised to arrive at a brothel and find an Indian working there. He also falls in love with his father (yet another case of incest). Surprisingly, no one has dared to take it to the cinema… although, on several occasions, Pedro Almodóvar has expressed his intention to do so.

Recently, Spain’s most famous filmmaker has gotten this fascination with the Western genre out of his system by releasing Strange Way of Life (2023). A short film, it’s a kind of domestic Western that brings together several of the most recurrent ingredients in Almodóvar’s filmography. A tribute to The Wild Bunch (1969), it does a pirouette by introducing a gunfight into the first carnal encounter between two lovers.

If we look to the pistol and the duel as symbols, we must admit that never has a trigger been used in a more apt manner. The film also takes the opportunity to reflect on what it means to be a man, once again using the classic notions of masculinity: active and passive, rigid and flexible.

Cormac McCarthy puts the point of view through human eyes that are amazed by the ineffable grandeur of the territory and its atmosphere. His novels are probably the most cosmic novels of the West. They demonstrate the insignificance of people in an exuberant world that can kill you at any moment. You can die from cold, thirst, sun, a shot, a stone, a lightning bolt that splits you, or a blow that knocks you out. War, blood and corpses are part of the landscape, just like a storm, a bush, or a rat. The territory remains atrociously beautiful after the annihilation of the great herds of buffalo… or the annihilation of people.

In Blood Meridian (1985), McCarthy underlines the insignificance of the human being by introducing a character who is hyper-conscious of it. Judge Holden — an enlightened man with albinism, deeply connected to the violent beauty of the world — displays sexual behavior that could be described as gay. Yet, his sexuality is almost always depicted in an atrocious manner by the author. Holden is impassive in the face of suffering, while living in a setting where the collapse of ethical codes — typical of times of war — reigns supreme. Holden is one of the most unforgettable characters that books have revealed to us, a kind of man-eating god, related to Doctor Manhattan from Watchmen (Alan Moore & David Gibbons, 1986). Ridley Scott pursued the film adaptation for years, but the project never came to fruition. Currently, it seems that a film version — directed by John Hillcoat and John Logan — is in pre-production.

In the novel Days Without End (2016) — written by Sebastian Barry, another Irishman — also draws on the atrocious beauty of the territory. He hones in on the story of two Civil War soldiers, who spontaneously get married and travel the country together, sometimes pretending to be a heterosexual couple. They embrace a trans identity, despite living in a world where nobody seems accepting of this. Barry offers a more anthropocentric view than McCarthy’s, which is more biblical.

In 2010, Kelly Reichardt and Jonathan Raymond — director and writer respectively — surprised us with Meek’s Cutoff, a Western film in which shooting is absent. The territory alone is enough to crush the psyche of the settlers. The guide, Meek, seems to once again represent the archetype of the lone ranger: always suspicious, inclined to remain single. Reichardt and Raymond then returned in 2019 with First Cow, a story of friendship between two men — a cook and a fugitive — who, like in the previous film, don’t shoot guns. It was based on Raymond’s novel The Half-Life (2004), which tells a story about the friendship between two women in the same setting, but 100 years after the time depicted in the film. Friendship, psychogeography and a sense of wonder are the specialties of this artistic pair, who are determined to reflect on how close the events of the Wild West are to us.

It’s clear that the question of virility in Indigenous cultures is probably not so exotic when compared to Western colonial interpretations. One only has to look at the importance of rites of passage (ceremonies that turn boys into men), how those whose sexuality isn’t easily classifiable are often considered to be sacred beings, or the relationship of the prominent North American Indigenous man with long hair, headdresses, war paint and beads. When you think about it, this outfit isn’t so different from the military finery of the white man — the plumage of the male peacock, or the big pistol on his hip. The boots with spurs, the scarf around his neck, the sheriff’s star and the gunslinger’s hat.

From John Wayne to the present, the Western genre has rolled out a whole garden of delights of masculinity for us to enjoy… and to reflect on.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.