North Korea working for ‘The Simpsons’? How the world’s most isolated country is secretly involved in Western animation

The discovery of a server with material from Amazon and Max series once again exposes an open industry secret: outsourcing to Kim Jong-un’s regime despite international sanctions

In his graphic memoir Pyongyang, Quebec cartoonist Guy Delisle recounts the time he supervised the animation of a series in North Korea. “The SEK [Scientific Educational Korea] studio may have been used at first to educate the masses, but today it serves, above all, to bring foreign currency (mainly French) into the country,” wrote Delisle.

“In terms of the relation between the quality and the price, it’s one of the best in the world,” Dominique Boischot, co-founder of the French production company Les Films de la Perrine, told Forbes in 2003. SEK — also known within North Korea as the April 26 Study, in commemoration of the date on which the Korean People’s Army was created — has not only been growing thanks to commissions from Europe; it has also been buoyed by its v on The Simpsons Movie (2007), Futurama: Bender’s Big Score (2007) and episodes of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (2003) and Avatar the Last Airbender (2005).

Given the rising tensions over Kim Jong-il’s nuclear program and the international sanctions which it triggered, no Western executive has since returned to talk to the press about the wonders of cheap North Korean labor. But this does not necessarily mean that North Korean animators have been left without work — a point that was made clear by the discovery of a server with work corresponding to the still unpublished third season of the Amazon Prime series Invincible and the Max animation Iyanu: Child of Wonder, which is scheduled to come out this year.

The files include comments, notes and instructions for the artists, such as “improve the shape of the character’s head.” A report titled How Well Do You Know Your Partners? by 38th North — a project of the American Stimson Center for North Korea Research — does not accuse the production companies of ignoring the sanctions against North Korea. Their analysts believe it’s a case of subcontractors subcontracting SEK, pointing out that the instructions were translated from Chinese.

“We do not work with North Korean companies, or any affiliated entities, and have no knowledge of any North Korean companies working on our animation,” Skybound Entertainment, the producer of Invincible, posted in a message on X (formerly Twitter), which also announced an internal investigation.

The person who discovered the server was Nick Roy, a cybersecurity expert who is fascinated by North Korea: he even has a blog where he records the virtual activity he detects in the region. It’s not a lot of activity, because the country’s online life mainly takes place on an intranet called Kwangmyong. “It is only accessible within North Korea and there is no known way to access it from outside,” Roy tells EL PAÍS. “A handful of senior party officials have access to the internet that we all use, and some people like students for a small period of time when they need it to investigate, albeit under surveillance.”

The cloud server that Roy accessed — which was poorly configured and could be accessed without a password — was located at a North Korean IP address, one of the few 1,024 in the entire country. The cybersecurity expert says that while he had read about such practices, he had never personally come across direct evidence before. Although most of the users who connected did so through virtual private networks that hid their location, the server was able to track accesses from three Chinese cities and from Spain.

The sickle, the hammer and the brush

Roy started his blog about the virtual world of Kim Jong-un’s country nine years ago. “I think my interest started when I saw The Vice Guide to North Korea,” he says. “The video was interesting because I think it was the first time I saw someone inside the country. I’ve always worked for network security companies, so I think I was naturally curious about how things worked there since it’s so walled off. Especially when I started to see that they have their own operating system, their own cell phones, I wanted to see how much I could find on the internet.”

Regarding the apparently high level of knowledge and specialization of North Korean computer scientists, Roy believes that “one of the things they do very well is focus on certain areas or industries.” “Right now they are focused on cryptocurrencies, not on taking money from just anyone with a bank account. When they want to obtain information, they tend to target experts in certain fields. If you don’t spread yourself thin, you can develop better capabilities to achieve your goals,” he reasons.

The computer scientist regrets not having been able to access My Companion, the Netflix-style entertainment platform used in North Korea, that features local productions. One person who has seen a lot of content from North Korea, especially in the field of animation, is Eduardo Naudín Escuder, doctor in Communication, Information and Technology of the Networked Society from the University of Alcalá de Henares in Spain, who wrote a paper on the topic.

In the study, Naudín not only analyzes the keys to national animation products, but also outsourcing to SEK, the only animation studio in North Korea. “Due to the nature of the country, it is impossible to know what percentage of production is local and what is international,” he explains to EL PAÍS. “What has been proven is that, for decades, North Korea has occasionally collaborated in the production of several foreign animated series and films. These projects are normally carried out through intermediary studios in countries such as China. That’s the key. As a general rule, no Western production company or streaming platform deals directly with a North Korean studio. Or at least that’s what they say.”

Naudín argues that North Korea “is not a shadow superpower of animated audiovisual production.” “What it offers are, basically, very low prices. There’s all there is. They can carry out very specific tasks at very competitive prices,” he explains. In 2003, Boischot told Forbes that “the price [of animating in France] would be five, six or seven times what SEK is charging.” Italy’s Mondo TV is another one of SEK’s most loyal clients: the North Korean studio help it make imitations of The Lion King and Pocahontas in the 1990s, and even a film about the life and miracles of Padre Pio in 2006.

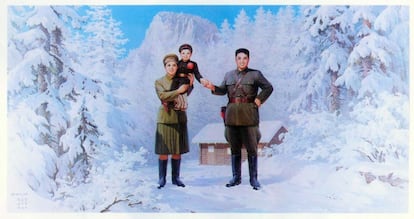

With animators trained in fine arts, SEK was founded in 1957 and has been a prolific producer of animated films and series that, according to Naudín, are “purely propagandistic” and “very weak in terms of narrative and style.” Some of SEK’s classics include the short-animated movie Pencil Bomb (1983), which is about a boy who falls asleep studying, has a dream in which he fights the Americans thanks to what he learned at school, and when he wakes up puts extra effort into doing his homework, as well as the long-running series Squirrel and Hedgehog (1977) and Boy General (1982), which also deal with war.

However, North Korean citizens do also have access to animation from abroad. Not only can Disney films be found in the thriving black market that many exiles have described, they are also sold in broad daylight and have even been officially broadcast. At one point in the documentary The Propaganda Game (2015), director Alvaro Longoria was surprised to find a DVD of Pixar’s Brave (2012) in a North Korean home.

Seohyun Lee, a U.S.-based defector who runs the YouTube channel Pyonghattan (a contraction of Pyongyang and Manhattan), said in an interview that she had legally watched movies like Cinderella (1950) and Robin Hood (1973) on North Korean television, and that Tom and Jerry cartoons (1940) were tremendously popular. This was also attested to last year by the South Korean newspaper Daily NK, which focuses on news from North Korea, which said that the live-action film version of Tom and Jerry (2021), starring Chloë Grace Moretz, was available on My Companion and was the most watched foreign film on the platform.

The curious who want to see North Korean work will have to settle for the episodes of series that are regularly pirated and uploaded by accounts such as the Russian YouTube account North Korean Cartoons, a showcase of how SEK has evolved over the decades, including its latest foray into 3D animation. But as Cinema Escapist’s Anthony Kao explained in 2018: “You don’t even need to fly Air Koryo to see its work. Chances are, you might’ve already unknowingly watched something that North Koreans animated.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.