Shark terrorizes the Olympic Games: Why we can’t get enough of sea monster movies

Netflix’s ‘Under Paris’ imagines a shark invasion during the Paris Olympics, becoming the latest to join in on a fiction phenomenon that shows no sign of slowing

Debuting in early June on Netflix, the movie Under Paris tells the story of a marine scientist, Sophie (played by the French-Argentinian actress Bérénice Bejo), who loses her entire crew when the shark they are studying, named Lilith, suddenly slaughters them. Years later, the scientist is living in Paris and trying to put that traumatic event behind her, only to have the past come knocking when the chip that has been implanted in Lilith is detected in the river that runs through the French capital — the odds of an ocean-dwelling shark swimming in fresh water be damned. From that moment on, Sophie begins a race against time to hunt down the shark and prevent further carnage from taking place during the 2024 Olympic swimming competition in the Seine.

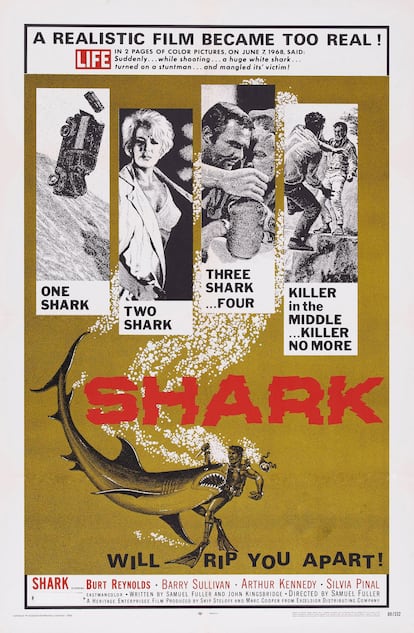

The film is directed by Xavier Gens, who has helmed horror movies as Frontier(s) (2007) and The Crucifixion (2017), and it credits six people as screenwriters. Under Paris has been a hit on the streaming platform, which announced after only a few weeks of its release that it had become the fifth-most-viewed full-length film in a non-English language in the history of the website. Under Paris invokes the trope of the public official (in this case, the mayor) who doesn’t want to call off the water events because it would undercut earnings from tourism in the area, a wink at Jaws (1975), the movie that started it all ― even if it there were earlier productions like Tiger Shark (1932) and Shark (1969).

Steven Spielberg’s masterpiece is considered the first shark-themed blockbuster, and it started a wave that, 50 years later, is far from going away. This summer, another U.S. shark horror flick, Something in the Water, is set to hit theaters. Veteran actor Richard Dreyfuss, one of the stars of the original Jaws, will once again take on the fanged predator in Into the Deep. Renny Harlin, director of the classic Deep Blue Sea (1999), just made his return to the sub-genre with Deep Water, a survival thriller in which an airplane makes an emergency landing in waters infested with sharks. A third installment of 47 Meters Down (2015) is also in production. And those looking for an even more extreme cinematic experience will soon have the recently announced Mummy Shark, which indeed follows a mummified behemoth of alien origin found in Egypt. That production is headed by Mark Polonia, the reliable creator of such films as Sharkenstein (2016), Amityville Island (2020), Noah’s Shark (2021), Sharkula (2022) and Cocaine Shark (2023).

“Two things that human beings, without a doubt, have in common are the fear of being eaten alive and fear of the unknown. Shark films offer both, from the comfort of one’s sofa or theater seat,” the marine biologist Susan Snyder tells EL PAÍS. Snyder is a devotee of shark films and author of the book Encyclopedia Sharksploitanica (2021), a reference book for the toothy sub-genre. “Floating in the deep, dark sea as a toothy fish with a big appetite circles beneath you is the stuff nightmares are made of.”

The biologist says the bulk of shark movies, starting with Spielberg’s hit, offer up a distorted image of shark behavior. In real life, their attacks on humans are isolated, infrequent and accidental. Christopher Golden, a prolific fantasy author who has also ventured into suspense territory in his novels, recognized on one occasion that “most likely, if a shark bites a human, it has confused their neoprene suit with seal skin.” The science represented in these stories rarely shines in its plausibility. Although such details like veracity rarely determine whether or not people like a film, the repercussions of Jaws were quite negative for the species: the increase in subsequent years of shark sightings and hunting competitions was dubbed “the Jaws effect.” Both Spielberg and Peter Benchley, author of the 1974 novel on which the film was based, had to campaign against the animals’ depopulation and expressed regret that their work had contributed to their persecution.

“The widespread killing of these beautiful creatures shows that the true monsters are humans, not sharks,” says Snyder who, nonetheless, believes that “public consciousness has changed” and that our passion for these animals, which has given rise to so many marine science careers over the last half century, has ultimately brought about a better awareness of the need to conserve and protect sharks. Initiatives like Discovery Channel’s Shark Week, seven days of content that the channel has aired every year since 1988, use the public’s fascination for these fish to educate, inform and correct erroneous perceptions through documentaries — even if Discovery has been subject to criticism in recent years for placing priority on spectacle and docu-fiction. “Kids love sharks as much as dinosaurs,” says the biologist. “I think that shark movies help us to continue being aware of them, and in a certain way, love them.”

Nazi shark

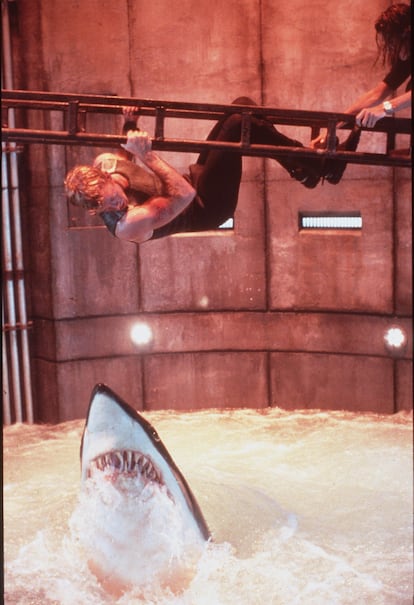

One reasonable concern about sharksploitation is that no successive project has been truly able to measure up to Jaws. Widely regarded by the industry, academics and fans alike as one of the greatest films of all time, one that blurs the boundaries between popular entertainment and art house cinema, its success was both impossible to replicate and too massive not to try. And so, though Spielberg prudently left the franchise, Universal produced Jaws 2 in 1978 with another director, and became responsible, in a way, for laying the foundations of sharksploitation. With a more comic, self-aware tone, the film abounded with exaggerated setups (one of the shark’s first attacks ends in an explosion, and throughout the film it even manages to board a helicopter), that were, if absurd, engineered to offer a satisfactory viewing experience. The movie managed, at any rate, to become the most successful sequel ever at the box office, though it was quickly surpassed by Rocky II (1979).

Writer Peter Benchley was not afraid to squeeze more juice, albeit with a certain sense of delirium, from the phenomenon he’d had a hand in creating: in 1994, 20 years after his massive hit byline, he published White Shark, a novel about a shark-human hybrid being that a scientist in Nazi Germany develops in 1945 as the weapon that will prevent Hitler’s defeat in World War II.

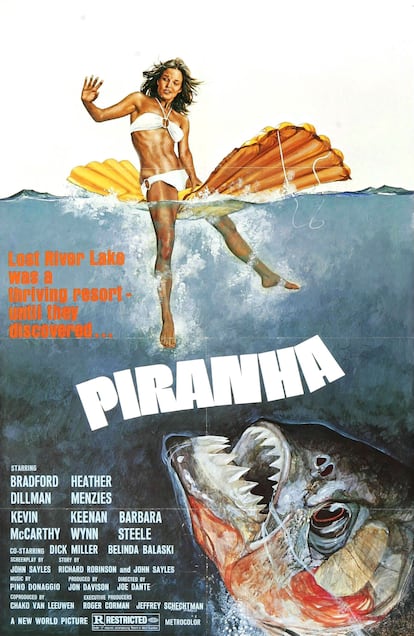

The same year as Jaws 2, Roger Corman, the recently deceased king of low budget cinema, brought Piranha (1978) to movie theaters. It was director Joe Dante’s first feature film, and Universal threatened to block its release, considering the movie a plagiarism of its own franchise that merely substituted another aquatic creature as the source of terror. Spielberg, who ended up becoming Dante’s friend and producing his Gremlins (1984), avoided legal action because he liked the movie so much that he referred to it as “the best of all Jaws copies.” The superlative laid the groundwork for another rule of sharksploitation: you don’t need a shark to make a shark movie. Crocodile movies like Lake Placid (1999) and Crawl (2019), or those that focus on giant snakes like Anaconda (1997), are also part of the “shark movie” phenomenon because the fictitious shark is, in essence, an abstract marine monster. Not surprisingly, and despite the fact that Jaws was based on the literary Moby Dick (1851), aquatic creature films like Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) and The Monster That Challenged the World (1957) served as influences for Spielberg.

Science jumps the shark

Are shark movies doomed to repeat Jaws, with diminishing results? “Short answer: yes. Jaws placed the bar incredibly high for shark movies,” says writer and biologist Susan Snyder. The long answer would be: “That is, up until 1999, when a new standard for sharksploitation was set by Deep Blue Sea. The appearance of the CGI special effects allowed for the sharks to be shown more frequently and with a wealth of detail. The highly important surprise attack scene became another one of the tropes that subsequent shark movies would copy.”

Built on the premise of sharks that have been genetically enhanced for research purposes, rendering them smarter and faster and which, of course, wind up escaping, the popularity of Deep Blue Sea — ever on the rise, thanks to years of video store rentals and television reruns — opened the door to further creative license when it comes to shark science. Deep Blue Sea employs climate change as the culprit behind this shark transformation, a plot point that has become a modern trope.

And somewhere in the far reaches of scientifically relaxed storylines we find Sharknado (2013-18), the six-film saga about a tornado that sucks in sharks and allows them to attack by land, sea and air (the sharknado presumably functions as a mammoth waterspout, supplying the animals with constant oxygen), and the diptych Megalodon (2018-23) in which action hero Jason Statham is blessed with the opportunity to fight a 75-foot prehistoric shark.

.“At the beginning of the 2000s, more realistic survival scenarios became popular,” says Snyder, who cites as examples the shark-happy Open Water (2003), The Reef (2010) and The Shallows, the latter by director Jaume Collet-Serra, and one of the subgenre’s best-reviewed representatives in recent years. As the umpteenth confirmation that all shark movies are monster movies, The Shallows is characterized by the contemporary urge to cloak the element of terror in metaphor. Its prologue tells of the death by cancer of the main character’s mother, and how her offspring’s overcoming of grief and recovery of her will to live will prove key in being able to face the great white shark that stalks her. Similarly, last year’s 47 Meters Down employs the not-so-complex image of a cage at the bottom of the sea to talk about depression.

This fertile moment for shark cinema (if the 2010s have been the sub-genre’s most prolific genre, our current era appears to be keeping pace) gives a viewer much to choose from. The possessed shark of Shark Exorcist (2015) or 2-Headed Shark Attack (2012), whose title creature had grown to have six heads by the fourth installment, offer takes that are blessedly free of melodramatic notes. Even those interested in the story Robert Shaw’s character tells in Jaws about the ship Indianapolis, which was sunk by Japan in World War II and whose survivors faced sharks, have their own dedicated feature: Men of Valor (2016), starring Nicholas Cage. “I support renegade filmmakers who know that what they’ve created will never be the next Jaws, but they make it anyway,” says Susan Snyder. “What’s next on the shark horizon?,” she asks. “I can’t wait to find out!”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.