Inside Pixar: The anxiety to be relevant with ‘Inside Out 2′

EL PAÍS visits the company that just let go 14% of its workforce and is hoping to repeat its 2015 box-office hit. In this sequel, adolescent emotions overwhelm the protagonist

As often happens when encountering our biggest idols and longest-awaited experiences, while visiting a place you’ve idealized for the first time, it’s common for excitement to dissolve, courtesy of a swift jolt of reality. Perhaps this is typical in the headquarters of many admired companies, which tend to be gray buildings with low-quality drip coffee. But if there is a firm that knows how to maintain excitement from start to finish, even when it comes to the joe, it’s Pixar. The minds behind Nemo and Dory, Buzz and Woody, the grumpy Carl from Up and the Incredible family can’t work their magic in a block of boring cement. Creativity bubbles up in every square inch of their offices in Emeryville, in the San Francisco Bay Area, which are adorned with posters, drawings and figurines from their latest creations: the new emotions of the long-awaited Inside Out sequel. Nine years after the first movie, which won the Oscar for Best Animated Feature, triumphed at Cannes and earned $860 million at the box office in the summer of 2015, its follow-up arrived in U.S. theaters last Friday. It is set in the mind of the protagonist Riley and stars a character who is as unimaginable a decade ago, as it is accepted today: Anxiety.

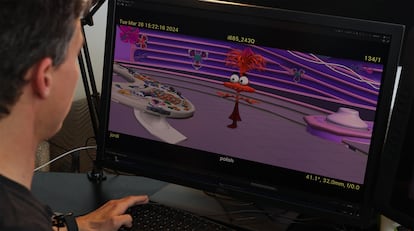

A teen Riley — complete with braces, pimples and drama — and her emotions are the stars in these halls and cubicles that serve as worksite for many of the employees at the company. Pixar employees some 1,200 people work, though at the end of May, it let go of 14% of its workforce, some 175 employees. (Disney has also been the site of some 7,000 recent lay-offs.) The characters’ constant presence is an apt reflection of the big expectations that the film has generated, both on and off the campus, where a large Luxo lamp welcomes visitors to a picturesque collection of glass-and-brick buildings interspersed with sports fields and a swimming pool. EL PAÍS visited Pixar at the end of March to check out its facilities and chat with its workers, including the director and creator behind the original Inside Out, Pete Docter; the director of the sequel, Kelsey Mann; the producer of the latest film, Mark Nielsen; and with one of the Spaniards who participated in the project, animator Jordi Oñate Isal.

It was Docter — one of the company’s first animators and today, one of its biggest stars — who, in 2015, inspired by his daughter Elie, created Riley, bringing her emotions to life, in addition to the ways in which they are managed by a child’s mind. He did not play a role in the development of the second film, though in a presentation for members of the press at an auditorium in the campus’ primary building (dubbed “Steve Jobs”) he admitted to feeling “excited” about its arrival in theaters. After the “significant impact” of the first movie, according to Docter, “it was time to explore the next chapter.” The timeline of its main character provided the ideal conditions for a sequel: now, Riley is a teenager and her head is full of much more than Joy, Sadness, Disgust, Anger and Fear.

In the sequel, four new emotions land with the grace of a bull in a china shop, only to become the new stars of the hour-and-a-half run time: Envy, Embarrassment, Ennui and above all, Anxiety, the movie’s real scene-stealer and the one who its creators are betting will dominate not just memes, but also merch sales, from movie theater popcorn boxes to sweatshirts and dolls. The decision to make Anxiety — who is orange, with bulging eyes, has a nervous laugh, a wild hairstyle and is voiced by Maya Hawke — the lead of the new movie did not happen by chance at a time when the conversation about mental health is more salient than ever. “I love the fact that it is going to speak about anxiety and say something hopefully meaningful. But also funny. We’re really excited,” says Mann.

In Riley’s new chapter, there are many more emotions — dozens were proposed at the beginning of the film’s production, in fact. They were culled (though some may appear in the final moments of the finished film, like the beloved Nostalgia) until the final cast was agreed upon. Just as important has been the process to define the film’s setting. Docter says that for the 2015 movie, his team created a huge set based on the mind of the little girl, but “you only got to see just a little bit of it” and that they wanted to keep exploring. “I made a list of all the sequels that I loved and all the ones I didn’t love, and I thought about why. The ones I loved all had something in common: they opened up new doors to a world that I didn’t know. The others were just repeats, they just went back to the same places. And I wanted to go to new parts of the mind, the ones I’d never been to. What’s really cool about being a director is I get to say, ‘let’s go in there’ and somebody does,” Mann says.

Nielsen continues: “There are so many places to go in the mind world. And Inside Out 2 takes you to a lot. You saw a few. There are more places in the mind world that these emotions end up going to and exploring. For example, the belief system is another really important place in this movie that didn’t exist in the first film, where Riley’s beliefs are born and where you can hear what they are in her.”

“And that little elevator that pops up in the first film, but you didn’t know it was an elevator?” he asks. “Because it wasn’t until we came up with the idea [of what it was] and worked it in. It’s really fun to try to link the two movies together.”

Nielsen and Mann say they had total creative freedom. “The only thing I asked them for from the start was that they let me introduce new emotions and to connect them to the last movie,” says Mann. It was important to figure out where they came from, how they were linked to the first film. From the very start, he was set on working with Meg LeFauve, the writer of the first film, and now, the second. Mann also collaborated with LeFauve on 2015′s The Good Dinosaur, which coincided with the birth of the Inside Out franchise. Together, the two mapped out the lives of the emotions and how to introduce them into the universe of the first, beloved five.

Jordi Oñate Isal has been working as a Pixar animator for 13 years and is one of the few Spaniards both at the company and among the 375 beings — all humans; no artificial intelligence in this movie’s crew — who have formed part of the project over the last three years. He’s the one who makes characters walk or laugh, according to the directions of the director, and he admits that Anxiety was the hardest to bring to life: “It’s an emotion that is a little bit different to create, and we’ve had to elaborate on it. Because what does anxiety mean, exactly?” His reflections speak to the difficulty of turning an emotion, an idea, an intangible, into a walking and talking cinematic being. “We’ve done it by thinking about the character’s behavior. It’s the one with the most complexity,” he says. But also, due to this challenge, the most interesting. “It has been the most fun. We are always trying to do new things and characters who are always laughing or who are easy to create don’t provide much challenge anymore, they’re the most boring for the animators.”

With the process nearly finished, Mann, the director, and Nielsen, the producer, explain half jokingly, half seriously, that if they had to define their current state with one of their emotions they’d be “between Joy and Anxiety.” Too much responsibility, excessive expectations? They hope that both the eager audiences and the animation company itself will be pleased with the film, which is the company’s 28th in nearly 30 years. It’s Pixar’s big bet, the film which — without Barbenheimers’ shadow — is expected to be among the biggest films of the summer of 2024. “Let’s hope so, we’d like nothing better, that sounds great,” say the pair. “With everything that we’ve been able to control, obviously we’ve tried to create a universal film, and hopefully it fulfills all expectations.”

That success, more than a hope, is starting to become a necessity. Even before the pandemic, all was not well in the house of Pixar. Beyond the lay-offs, its films have often debuted to a distinct lack of fanfare, and many haven’t even arrived in theaters. In 2019, Toy Story 4 enjoyed some success, but only the most fervent fans will remember the production company’s subsequent releases: Onward, Soul, Luca, Red and even the surprisingly unsuccessful Lightyear, which barely made back its $200 million budget at the worldwide box office. There have been some gems (like Pixar’s latest, Elemental, an Oscar nominee), many of them overlooked. “We are continuing the story of Inside Out, which was very much loved. Nine years ago, it touched the world and maybe even made people think differently,” says Nielsen. “That’s why there was so much responsibility when it came to making a sequel.”

“You have to make something that has something to say, beautiful, super-entertaining, fun, all the things we love that are in Pixar films. But also that has deep meaning, that gives people something to talk about and to walk away with,” says Docter. “Above all, teenagers,” says Mann. “If I had had a movie like this when I was that age…” he says, sharing with the press that he has dealt with anxiety “since I was a teenager,” and that in the film, he looked to provide a twist by not treating it “like a kind of villain, an antagonist,” as it is often presented. “My anxiety has also helped me, it says, ‘You got to get up on the stage, you have to be ready, make sure of it.’ Like anger, which in small doses can be helpful, until it goes too far and can take over. I always wanted this film to be about learning how to manage anxiety.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.