‘The best kept secret in the industry’: How Pixar makes the costumes for its films

In addition to designing computer-animated characters out of its California headquarters, the clothes they wear also have to be made. EL PAÍS visited Pixar Animation Studios to discover the unknown work of digital tailors

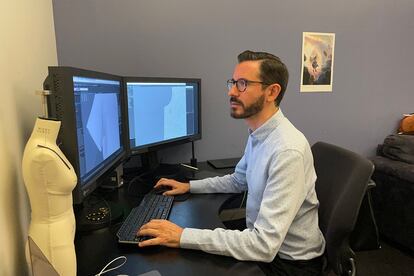

In one of the four buildings that make up the huge Pixar headquarters in Emeryville, California, there are several rooms dedicated to patterning and sewing garments. There are also several offices — mostly arranged for two people each — in which said garments are brought to life on a screen. In a matter of seconds, as if by magic, the clothes wrinkle, move, become transparent, resize and twist endless times, while being worn by a computer-animated character.

“It’s the best kept secret in this industry,” explains Trevor Barrus, the head tailor for Elemental — the new Pixar film that deals with the balance of the four elements through the unlikely friendship between Ember (fire) and Wade (water).

The most important animation studio in the world has a tailoring team made up of approximately 20 people. They aren’t costume designers per se, but they’re not computer simulators, either. “We’re somewhere between technique and creativity,” explains Barrus. They’re essentially virtual tailors, who work with the sketches drawn up by the character designers — who initially imagine the clothes — and the animators who simulate movement. They turn the ideas into real-life prototypes, before translating them to the screen.

“In this case, [the characters of Elemental still have] human forms or proportions, but in addition to that, they have their own materiality. Fire, wind, water and earth move differently… hence, the materials they wear are different, which is why Ember wears metallic mesh clothing and Wade wears waterproof clothing, for example.”

For eight months, Barrus — who previously worked on films such as Lightyear, Luca and Inside Out 2 — and his team of 20 people have been in charge of giving movement to metal, nylon and cotton, while deciding on lengths, colors and patterns and experimenting with lights and shadows. “Compared to other projects,” he explains, “there isn’t much equipment. In fact, all the characteristics of [Elemental] are different.”

The film’s characters come out of pure fantasy. Hence, more imagination than realism was required. “Oftentimes, it’s about removing elements instead of adding details — a process that is sometimes just as complex. The goal is for nobody to notice the wardrobe; it needs to seem like something natural,” he notes. But, keep in mind that, in the world of Pixar, the word “natural” has a totally different meaning.

During the production of many Pixar films, garments are made by hand and tried out on mannequins or people, before moving on to digital simulation. “There’s a lot of attention spent on how we dress the characters. Here, we have a constant dialogue with all departments all the time. In a film that uses real images, for example, dressing the character based on their personality or the time period matters. You have to take into account the setting, what the main character is wearing compared to the secondary ones, etc,” explains Juan Carlos Olmos, who spent more than 16 months designing the clothing for the main character in Elio (set to be released in 2024). “Even if the story is more realistic, the clothing has to be stylized: buttons must be larger than usual, materials require a different thickness, small details are very important here.”

Set in an indeterminate future, the 11-year-old protagonist’s garments are made from upcycling — that is, from the remains of other materials. The team had to try making clothes from — among other things — old fabrics or plastic bags, before transferring these elements to the screen. “It’s something like building and then rebuilding on top of what has been built. First, because the proportions are different: these aren’t human bodies. For this reason — although it may seem paradoxical — we have to break the traditional rules [such as putting in a wrinkle or a fold where there isn’t one]. And second, because the idea is that this simulated and stylized wardrobe will influence people. They’ll remember it — it may even become a costume. This is only achievable by enhancing certain details.”

The first time Pixar created a digital tailoring department (beyond the costumes that were drawn alongside the character) was with Monsters Inc. (2001). “It was a kind of reverse engineering. The real clothes were made and then a program would translate them into patterns in two dimensions, because nobody had any knowledge of pattern making,” Olmos explains. Little by little, they were creating their own internal programs to clothe the characters in 3D designs. One of the first programs, in fact, was known internally as Edna Design, alluding to the designer character in The Incredibles. With Edna, they created the clothes for Up (2009).

The digital tailors currently work with programs such as C3d and Fizt2 — the latter having won a technical Oscar. “Today, we’re able to orient the patterns according to the simulated fabric we choose; we can drape and simulate the elasticity and movement of a specific fabric, or play with the weight of different layers,” Olmos says. However, for him, Pixar’s great contribution to the main wardrobe isn’t on a screen. “The most important thing is to have people with knowledge of traditional tailoring in the digital tailoring teams, because in order to be able to represent a shirt well on the computer, you have to first know how to make a shirt, even if you have to transform it later.”

“Having knowledge of fashion is also critical. A character in a woolen suit doesn’t communicate the same thing as with a polyester one. We also have to know how and why they dressed as they did in specific times.”

Both Barrus and Olmos specialized in animation. In their previous work, they came across garment simulation programs that are often used by fashion designers as well. They ended up learning how to pattern and design clothes. “I never had anything to do with art until I needed it professionally. But it’s true that, within digital tailoring, there’s also a field of opportunities for designers,” Barrus emphasizes.

Olmos — who trained at New York’s Parsons and FIT fashion schools — stresses how the right software and knowledge can also change the apparel industry with issues that go far beyond the hackneyed metaverse: “While many computer tools have been developed to make clothes, studying [fashion and tailoring] and knowing how to use the right tools saves material, resources and energy.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.