The director who shook up Disney and Hollywood animation with a mermaid, a genie from a lamp and a Polynesian princess

John Musker, who headed up ‘The Little Mermaid’, ‘Aladdin’ and ‘Moana’, is debuting a short film after announcing his retirement from a 40-year career. ‘At Disney in the 1990s, there was an emperor, but there weren’t 10 emperors’

When Steven Spielberg told Disney in 1989 that the movie that John Musker (Chicago, 70 years old) had made for them was going to sell $100 million in tickets, no one believed him. The new project wasn’t based on a classic story like Cinderella. What’s more, it featured reggae sung by a crab. Was this really what was going to lead the studio out of its long dry spell? “It was done with a sense of almost naivety,” Musker recalls. “We weren’t trying to imitate. It was more freeing. We didn’t have past successes, like ‘Is your movie going to be good as The Little Mermaid?’ We hadn’t made it yet.”

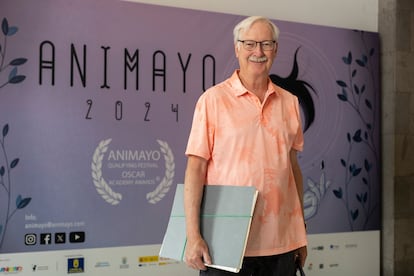

“On the inside, I’m still an eight-year-old boy,” the director jokes, now gray-haired and with many successes under his belt. He’s at the Animayo International Summit in Gran Canaria, Spain, which took place last week, and where he gave master classes and lead the international jury in pre-selecting an animated short film that is now sure to be shortlisted for the Oscar race. He says that he’s happy to still be learning. Over four decades, he has co-directed, alongside Ron Clements, projects that depend on the work of massive teams like The Great Mouse Detective, Aladdin, The Little Mermaid, Hercules, The Princess and the Frog, and his leap to digital, Moana. In his new short film, I’m Hip, which stars a feline jazz singer, he has returned to drawing at long last. He hadn’t played that role since sketching the fearsome hunter who shoots Toby in The Fox and the Hound.

Before Ariel packed out theaters, the then-president of Disney, Jeffrey Katzenberg, told her creators that he wasn’t harboring many illusions about her film: “Movies about girls don’t work.” The Little Mermaid, he said, would never best Oliver & Company. “The big eye-opener was when we had a preview. It played so well to a public audience, all ages, including adults,” says Musker. “They decided they were doing two different ad campaigns. One was a silhouette of a mermaid, looking wistfully out. I think they saw there was a way to treat it a little more adult, classier. It has a lot of fun as a comedy. But there’s an emotional story, not just silliness. I mean, the Hans Christian Andersen’s story was that,” he tells EL PAÍS, who was invited to Animayo by the festival’s organization. Musker’s team had another curious exchange with the legendary Katzenberg during work on Mermaid: “Die Hard had been a box-office hit. So he came into the office saying, ‘We need The Little Mermaid to be more Die Hard. That’s how we got the second action sequence, with an Ursula who is as big as the building in Nakatomi Plaza.”

He says that, even so, he prefers Katzenberg’s reign of terror to that which followed: “Moana was a very difficult project. It was our idea, but with Pixar and John Lasseter, our story kept changing hands. In the ‘90s, we had Jeffrey. He was an emperor, you know. But there weren’t 10 Jeffreys. Now, you have too many people to satisfy, before we didn’t have 15 directors telling you how to make the movie. But in some ways, they were right, it was a good thing,” he says, conciliatory.

Not for nothing is Moana the most popular movie on streaming platforms, according to numbers that have been released by Nielsen. But Musker’s granddaughter is not a big fan. “I like Coco better,” her grandfather says she once told him. She is his hardest critic. Perhaps due to this harsh regime at home, he still got nervous a few months ago when he played his new, personal musical short — drawn over the course of five years — for his friends from university. That’s not as surprising if you keep in mind that these buddies include Pixar founder John Lasseter; the director of The Nightmare Before Christmas, Henry Selick and the director of The Iron Giant and The Incredibles, Brad Bird. Tim Burton also attended their school, in the year below them. In the short, which was also presented at Animayo, they all appear in caricature. As do his old bosses. They’re the villains.

Musker, who is tall and smiling, with a glowing complexion and floral shirts, could pass for any retired guy in Gran Canaria, resting after a life dedicated to business (in actuality he never stopped working, though he did retire from his post at Disney in 2018.) But this is not your average retiree: he’s the only one, for instance, who has been able to trap Aladdin’s Genie. The character is immortalized in a watch made just for Musker, which he has worn on his wrist since the film’s debut in 1992. This modern magic lamp is a reference to the scene in which the character says he’s got an “itty bitty living space.” Musker is the creator of the iconic persona, and the man who directed Robin Williams in one of the best animated roles in the history of film. “Working on his hundreds of improvised takes is one of the most memorable moments of my life. That and the songs of Howard Ashman,” he says, still in mourning for the lyricist.

Ashman died from AIDS just before Beauty and the Beast debuted. He never saw the massive influence that his compositions would have. “He told us he was sick when he was already in the last months of his life. He lost his voice and couldn’t sing the last ones,” Musker says of the man who created songs like Kiss The Girl and Friend Like Me.

Perhaps Ashman’s musicality is what was missing on the greatest failure of Musker’s career: “Treasure Planet (2002) is a cult classic today, but its opening weekend was devastating. It was the movie that I had been trying to sell to Ron Clements since the ‘80s, and they took it so that we wouldn’t go to Dreamworks with Katzenberg, who we could never talk into it. They knew that was a good selling point to keep us at Disney. It did help keep us, at least for one movie. But after Treasure Planet, we couldn’t get another movie going at Disney. We thought it was because we had lost our credibility. It was another era of animation, and Disney was moving away from hand-drawn.” And then came the indecent proposal. “After Toy Story, they proposed that we convert all the classic films into digital animation. I told them I’d commit harikari first,” he said, driving an invisible katana into his gut.

“The message should not get in the way of the emotion”

Like the actors who disappeared with the arrival of silent film, Musker might never have returned to the company where he even met his wife, who was a librarian in Mickey’s offices (perhaps the most atypical job there is in a movie studio). But despite everything, they brought him back in 2009 to update the Disney princess, once again, for The Princess and the Frog. And he pulled it off. “We weren’t trying to be woke, although I understand the criticism. The classic Disney films didn’t start out trying to have a message. They wanted you to get involved in the characters and the story and the world, and I think that’s still the heart of it. You don’t have to exclude agendas, but you have to first create characters who you sympathize with and who are compelling. I think they need to do a course correction a bit in terms of putting the message secondary, behind entertainment and compelling story and engaging characters,” says the animator, who recalls that on Aladdin, which debuted amid the Gulf War, he had to disguise the name Baghdad with its anagram Agrabah: “Because of the war, we couldn’t even go there to do research. Our big research took place at the Saudi Arabian expo at the Los Angeles Convention Center.”

Nor does he like every detail about his ideas being translated into new forms: “Companies are always like, ‘How do we reduce our risk? They like this, right? We’ll just do it again and sell it to them in a different form.’ Or they think, ‘Well, we could make it better.’ I think there was a question even with The Little Mermaid. They didn’t play up the father-daughter story, and that was the heart of the movie, in a way. And the crab — you could look at live animals in a zoo and they have more expression, like with The Lion King. That’s one of the basic things about Disney, is the appeal. That’s what animation does best.” Now it’s Moana’s turn to get the live-action treatment. “I hope that they do it well, but we have nothing to do with it,” he says.

“If you do something that is animated, take advantage of all its qualities and imagination,” says the filmmaker, who has never made sequels, and who points out Spider Man: Into the Spider-Verse, The Mitchells vs. the Machines, My Neighbor Totoro and the first Despicable Me for their use of all available tools. “I didn’t like the later ones so much,” he says.

At 70 years old, Musker is happy to keep making short films to keep himself entertained and learning new techniques that pertain to his passion for cartoons. He even captured his granddaughter (in I’m Hip) humming along to his latest animated melody. He’s still hopeful about adapting Mort, from Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series, the book that he’s kept close throughout his entire career. No one wants to buy the story because they think it’s “too dark”: “It’s even hard for Henry Selick to sell projects. They’re just risk-averse. It’s like, we’re going to spend a lot of money and we want to make a lot of money.” Not even Steven Spielberg can get his every project greenlit. Musker warns: “Just like how in the seed of every failure is a success, in the seed of every success is failure. Too much control kills projects.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.