How ‘a simple movie about a guy who throws punches’ became an unexpected classic

Prime Video hosts the debut of ‘Road House,’ a remake of one of the 1980s’ most beloved B-movies. The original’s nonsensical plot and buff Patrick Swayze have kept it near and dear to our hearts, and police departments have even deployed it in diplomacy trainings

Last Thursday, Amazon Prime Video saw the arrival of Road House, a new version of the 1989 film by the same name, this time with Jake Gyllenhaal in the leading role and filmmaker Doug Liman behind the camera. This remake keeps the original’s title, a similar plot and its focus on action sequences, but there are some clear differences: the fights are bigger, the settings more spectacular, UFC champion Conor McGregor was recruited to play the boss villain and production values, bolstered by an $85 million budget and Hollywood A-listers, are clearly much higher. An ambitious project, and one that counts with diverse resources with which to satisfy many of the expectations of fans of the 1985 version, which was more modest and had less pretensions, but which, after an acceptable showing at the box office, became a legend amid VHS rental stores and late night reruns. It was the kind of classic that was made possible by its willingness to pull out all the stops.

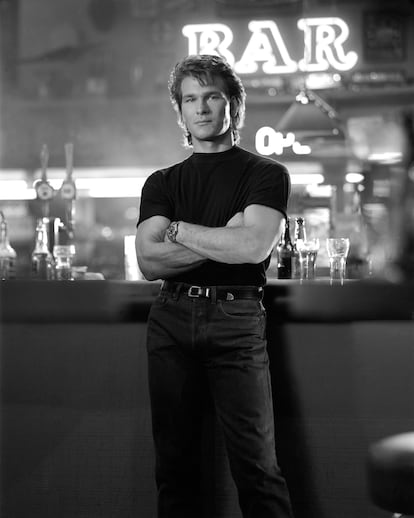

With Patrick Swayze in his golden boy era after the triumph of Dirty Dancing (1987), the original Road House told the story of James Dalton, a bouncer famed for the extreme efficiency with which he did his job. A man hires him to help clear out the riffraff from a bar the guy owns in a small Missouri town. Dalton, in addition to being a brilliant puncher, is a no-less-brilliant doctor of philosophy (a plot feature that did not make it into the 2024 version), who abandoned academia when he did not find “the answers he was looking for”, as he explains in one scene from the film. Those who do encounter definitive answers are the vandals who dare approach Dalton’s domain with impure intentions. Their conflict escalates to the point where our hero ends up forced to dismantle the local mafia, sustained by a corrupt police force, in order to successfully complete his peacekeeping mission.

“It is what it is, a plain and simple movie about a guy who comes to town to throw punches, who saves folks from the reigning kingpin because he can take on the bad guys, and gets the girl,” Álvaro Ruiz de Gauna, author of the book El cine de acción que ya no se hace: 50 películas que marcaron una época (Action movies like they used to make them: 50 films that defined an era; 2017, Dolmen Editorial). “But it’s different from Stallone and Schwarzenegger’s shooter and sucker punch movies. As ‘80s as it is, it departs a bit from what was being done at the time. It’s like a Western moved into the present. If you think about it, it has the same plot of Pale Rider [1985], and at the same time takes a page from Shane [1955]. A gunslinger, in this case a nightclub bouncer, who goes to a typical Midwestern town and frees it from the evil landowner who has everyone living in fear.”

Ruiz de Guana says another element that sets the film apart is the quality of its action sequences. “It has very good fights, particularly the one between Patrick Swayze and the main henchman, which is quite raw and realistic. Plus, there are knifings, and after a few blows the protagonist gets tired and sweaty, he’s hurting. He is not a superhero, unlike other action stars,” says the writer. Choreographer Benny Urquidez a.k.a. The Jet, a longtime collaborator of Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung, was largely responsible for this part of the film, and looked to import the forceful, hyper-technical style of Hong Kong martial arts cinema. The actors shot the fights without stuntmen, according to supporting performer Sam Elliott, who said, “They were kicking my ass the whole movie.” Urquidez, an American full-contact pioneer, was so taken with Swayze’s performance and physical conditioning that he tried to convince him to go into a career in kickboxing.

Roundhouse of glory

But Swayze wasn’t destined to limit himself to kickboxing, nor would he spend much time making action films. In the wake of his enormous success in Dirty Dancing, he knew just how to exploit his heartthrob status. Aside from the fight scenes, Road House also featured a romantic storyline between him and the actress Kelly Lynch, not to mention numerous scenes with a shirt-less Swayze. Even Road House’s promotional slogan riffed on its protagonist’s previous star role: “The dancing’s over. Now, it gets dirty.” An injury he incurred on set led Swayze to look for work outside the genre, and after declining roles in Tango & Cash (1989) and Predator 2 (1990), he starred in the film that would cement his status as romantic lead: Ghost (1990). Still, he later would return to action blockbusters in order to deliver another instant classic, Point Break (1991), in which he translated the mystic aura he’d channeled in Dalton to his role as a surf guru.

Alcoholism gradually dimmed Swayze’s shine, and the actor died in 2009 of pancreatic cancer. “In the late ‘90s he did a truck movie called Black Dog [1998] that is entertaining. It’s good, I laugh a lot when I watch it, but it did give the feeling that Patrick Swayze was taking any role that came his way,” says Ruiz de Gauna.

The original Road House was produced by a man who, in the economic sense, was the ultimate wizard of action films in the United States of the 1980s: Joel Silver, who already had credits under his belt for none other than 48 Hrs. (1982), Commando (1985), Lethal Weapon (1987), Predator (1987) and Die Hard (1988). In addition to hiring The Jet, Silver also brought along the editors from many of his previous films and one of Hollywood’s most experienced stunt coordinators, Charlie Picerni. But according to director Rowdy Herrington, Silver’s contributions to Road House went even further: he came up with the film’s most famous phrase, “I used to fuck guys like you in prison”, which one of the henchmen says to Dalton before the leading man kills him by ripping out his throat. Marshall Teague, the actor entrusted with delivering the storied line, said his mother leaped out of her seat upon hearing that part of the dialogue at a preview screening, shouting, “That’s my boy!”

Upon the film’s release, critics were not entirely receptive. Roger Ebert was one of the most accommodating, but not by much: he said it was enjoyable if “viewed in the right frame of mind”, but it was “right on the edge between the ‘good-bad movie’ and the merely bad.” However, that didn’t keep the film from racking up a decent commercial performance, and it found a growing audience throughout the years thanks to the popularization of cable television in the United States. In 2020, 31 years after its release, it became the most replayed film in that medium. Ben Gazzara, who plays its villain, said out of all the movies on which he’d worked, Road House was the one he’d re-watched the most. In an episode of Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown (2013), the series’ eponymous celebrity chef declared his admiration for Road House, a love that was shared by his scene partner, actor Bill Murray. “You can deconstruct this film forever. The more you watch it, the more mysteries unfold. Vastly under-rated film,” says Bourdain. “I’ve never seen anyone enjoy Road House more than I do,” Murray responds.

The movie, which also includes a sequence featuring a monster truck and live performances by famed Canadian guitarist Jeff Healy, was utilized by the New York police department to teach diplomacy to 22,000 officers, part of a mandatory retraining course instituted in response to the chokehold death of Eric Garner, a Black man whose final words, “I can’t breathe”, helped spur the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. In the scene used by the NYPD, Swayze’s character shows his coworkers at the bar the three rules for avoiding violent conflicts: expect the unexpected, don’t instigate and be nice. Of course, the revelation that police officers were watching Road House as part of a solution to a crisis of institutional racism and abuse of authority was not taken well by the public, and the city’s mayor at the time, Bill DeBlasio, had to make sure that the training program was not relying on its footage alone.

The new Road House premiered to its own polemic: its direct-to-streaming release has angered its director, Doug Liman, who has refused to promote it, and Silver himself, who returned to produce the new version, was fired by Amazon for ambiguous reasons (the company says Silver verbally abused two workers, while the producer’s camp attributes the break to his refusal to use artificial intelligence during last year’s actor strikes). The movie, nonetheless, has been favorably received by the critics. Now for the hard part: to stake its claim on the collective memory far beyond what its makers would have dared to imagine.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.