A version of ‘Dune’ by Jodorowsky: One of the most influential films in the history of cinema that was never made

With a stellar cast, an unprecedented production design and music by Pink Floyd, it had everything required to become one of the biggest films of the 20th century. But no one in Hollywood wanted to support it. It turns out, however, that there was no need: today, it’s a cult classic, without even existing

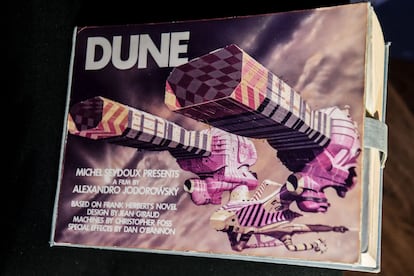

In November 2021, Christie’s broke a record by auctioning off the most expensive storyboard in history: that of the adaptation of the science fiction novel Dune, the film that was ultimately never made by Alejandro Jodorowsky. It sold for $2.9 million — almost 110 times the opening bid —, becoming the second-highest-priced book sold by the Parisian branch.

More than 3,000 drawings — spread over 28 pounds of paper — serve as a complement for the best cosmic epic of all time. Published by the writer Frank Herbert in 1965, the novel opened up debates about ecology, colonialism and extractivism. It took readers to the desert planet Arrakis, coveted for the spice melange: a drug with which to transcend space and time, key to the economic system of the universe.

While fans have been counting the hours until the premiere (March 1) of the second part of Dennis Villeneuve’s version of Dune — starring Zendaya and Timothée Chalamet — many nostalgists continue to demand that attention be paid to what is considered to be the most influential film adaptation of the story... even though not a single frame was ever shot.

In his excessive ambition, the multifaceted Chilean-French director Jodorowsky wanted the film to have Pink Floyd as the soundtrack and a cast with icons such as Orson Welles, Salvador Dalí, Mick Jagger and Gloria Swanson. But, in the end, everything fell apart.

Still, a creative dream team would emerge from the process, led by the cartoonist Moebius (the pseudonym used by Jean Giraud), the plastic artist H.R. Giger and the screenwriter and special effects supervisor Dan O’Bannon. In 1975, the three of them were still unknown. They would subsequently take the lessons they learned from their work on Dune and pour them into the creation of Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979). And, from the embers of the attempted production process, there remains a documentary — Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013), directed by Frank Pavich — which contributes to enhancing the legend.

By the time Dune was published, Jodorowsky had already accumulated a certain cult following. His direction of El Topo (1970) — a psychedelic delirium, in which he also played the violent cowboy protagonist — would serve as the founding film of the so-called “acid Western.” Furthermore, it would become the first midnight movie: a clever New York distributor decided to show it only at midnight because it was — as its poster proclaimed — “too strong to show any other way.” Of course, the lines went around the block.

The opening night, John Lennon went to see El Topo with Yoko Ono. He was fascinated by it, watching it three times. He bought the rights to screen it throughout the United States and asked his manager — Apple Records boss Allen Klein — to give Jodorowsky $1 million for his next film, The Holy Mountain (1973). Klein later wanted to convince him to adapt the novel The Story of O, but by then, the father of psychedelic cinema was caught up in more mystical matters.

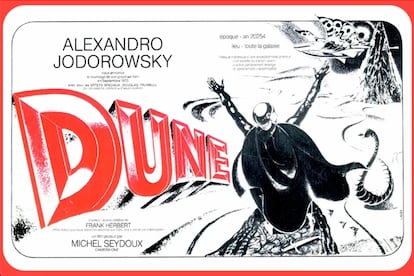

French distributor Michel Seydoux brought El Topo to Europe. He also gave Jodorowsky carte blanche to produce whatever he wanted. According to what the Chilean-French director confessed at the time, a deity appeared to him in a dream, revealing that Dune would be his next film. “I got up at six in the morning and — like an alcoholic waiting for the bar to open — I stood at the door of a bookstore where I could buy the book. I read it in one sitting, without stopping to eat or drink. As soon as I finished it, one minute after midnight, I called Seydoux to say, ‘Let’s do Dune!’”

He would have total creative freedom. Jodorowsky’s promise was that the film would cause viewers to feel the effects of LSD, without having to take it. He bought the rights for next to nothing in 1974. Afterwards, he began recruiting what he called his “spiritual warriors.”

He found Moebius when he was still just Jean Giraud, creator of Blueberry, a Western comic series. But the pseudonym he used for the galactic comics was about to take off. Jodorowsky passionately dictated the script to the cartoonist, while Moebius outlined the sequences and characters. When the storyboard was complete, they went to Los Angeles and planted themselves in the office of Douglas Trumbull, creator of the special effects for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), by Stanley Kubrick. “He didn’t [give us his attention]: he answered the phone about 40 times during our conversation. He [was] a very good technician, but he wasn’t my spiritual warrior,” Jodorowsky laments in the documentary.

Walking through Hollywood, they went to the movies. Dark Star (1974) was playing, directed by John Carpenter. In it, a certain Dan O’Bannon had done everything: he had been the screenwriter, protagonist, editor and special effects supervisor. A spiritual warrior. He received a call from Jodorowsky — they smoked a joint and nothing more was said: “Sell everything you have and come to Paris. Your life is going to change.” Indeed, it would change, but many years later, after he worked on the script for Alien.

The basic technical team was completed with Chris Foss, an illustrator of science fiction book covers. He was asked to design spaceships in the form of “jewels, mechanical animals, soul mechanisms, uterine vessels [and] antechambers for rebirth [in various] dimensions.” Foss would end up serving as an esthetic consultant for Superman (1978), Alien and Flash Gordon (1980).

In the casting call, Jodorowsky let his fantasies run wild. He had his 12-year-old son Brontis train in martial arts to play Paul, the story’s messiah and protagonist. He wanted David Carradine — who was very popular at the time for his Kung-fu series — to play Duke Leto, leader of House Atreides (one of the Great Houses of the feudal interstellar empire). Gloria Swanson would be one of the reverend mothers of the Bene Gesserit Brotherhood. Mick Jagger was supposed to be the villainous warrior Feyd-Rautha, a role that would be played by another rockstar — Sting — in David Lynch’s 1984 version of Dune.

As for Baron Harkonnen — that morbid monster who floats, thanks to antigravity implants — the director searched for someone who had the character’s enormous stature and girth, ultimately settling on Orson Welles. Jodorowsky boasts of having searched the Parisian restaurants until he found the famous actor and filmmaker (who was drunk). He bought Welles another bottle of wine and promised him that, if he came out of retirement to take on this role, he would bring his favorite chef to cook for him on set every day.

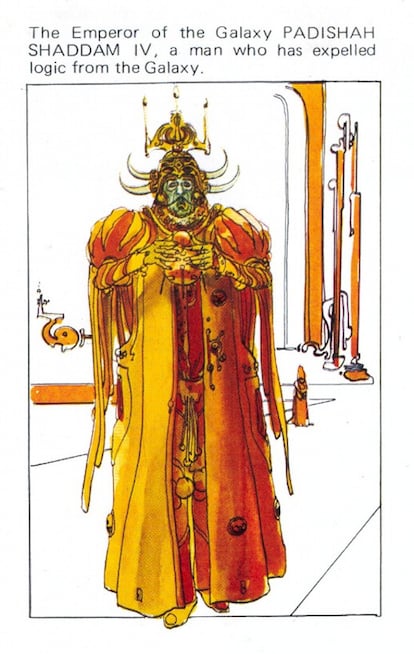

The Spanish artist Salvador Dalí simply had to be considered to take on the role of the evil Emperor Padishah. He finally agreed with one condition: to be the highest-paid actor in the world. Jodorowsky offered him $100,000 per minute on screen. But he had a trick: the painter would only appear in the film for three minutes in total. The rest of the time, he would be embodied by a robotic double, due to the emperor’s panic about being killed.

Dalí gave in, but with one last requirement: that, following the filming, the android would end up in his museum in Figueres, Spain. But as time went on, he added more extravagant demands: he wanted a throne in the shape of a toilet with two crossed dolphins; he wanted his friends to be cast as extras, like courtiers; he even wanted a helicopter to shuttle him around.

The singer Amanda Lear — then the official companion of the surrealist director — warned Jodorowsky: “Dalí can be very destructive. If he participates, he’ll do everything in his power to kill the film.” Through her complicity, Lear won the role of Princess Irulan.

It was Dalí who introduced the Chilean to a catalog of an unknown Swiss artist: H.R. Giger. His work distilled all the darkness that would encompass the planet reigned over by the evil Harkonnen family. In the airbrushed drawings that Jodorowsky requested from the artist, it’s easy to identify the style that would be recreated four years later for Alien.

The space epic quickly got out of hand: its director wanted it to last between 10 and 14 hours. At least $5 million of the budgeted $15 million had already been spent on pre-production costs alone (Star Wars, released a year later, cost a total of $11 million). They knocked on doors all over Hollywood in search of financing and distribution guarantees, sending copies of the storybook to studios such as MGM, Universal and Warner Bros. It’s estimated that about 10 copies were distributed to the major studios… and they all said no. A Disney executive defined it as the Concorde: “An exceptional plane that will never fly over these lands.” Of course, Hollywood would immediately exploit many of Jodorowsky’s ideas.

Immediately after its cancellation in 1976, the influence of his version of Dune appeared in several blockbusters.

In the documentary filmed more than three decades later, the use of Jodorowsky’s ideas in other franchises is clearly demonstrated. The vignettes drawn up for his version of Dune are compared with specific examples from films that were actually produced. For instance, in Star Wars, the lightsaber fights or Luke Skywalker’s training session with a floating robot are recognizable. In Flash Gordon, the staging and characters within the galactic palaces are nearly identical to the drawings. In Terminator (1984), the camera belonging to the cyborg — which processes whatever data crosses its path — is eerily similar to what appears in the sketches for Dune. And, across the board (except for the ultra-polished vision of 2001: A Space Odyssey) the rebellious esthetics and the vast amounts of galactic junk extend to all kinds of franchises, from Star Wars to Guardians of the Galaxy.

Today, the filmmaker Nicolas Winding Refn — best known for Drive (2011) and other contemporary, hallucinogenic flicks — maintains a close relationship with a 95-year-old Jodorowsky. Recently, after a dinner at his Paris home, he attended a private screening with the Chilean, explaining it to him scene-by-scene. He agrees with critics who say that “if you follow the trail, it often leads to Jodorowsky. Everything is part of a chain: without Alien, there would be no Blade Runner… and without that, there would be no William Gibson, nor would there be The Matrix.”

“It would have been interesting to see what would have happened if the first space opera of its kind had been Dune instead of Star Wars,” Refn notes. The truth is that we will never know if Jodorowsky’s Dune would have resulted in the genius work that his fans claim, or if it would have dissolved into a pompous, tacky delirium.

An invisible thread connects his failed project to Villeneuve’s Dune: Part Two: the presence of actress Léa Seydoux, who is the great-niece of Michel Seydoux (Jodorowsky’s producer). Of course, if you ask the versatile creator, he’ll tell you that he hates both adaptations. His children had to drag him to David Lynch’s house. He himself confesses that he was about to start crying when he took his seat and — as the footage unfolded — he broke down, because it seemed like “bullshit.” The film produced by Dino and Raffaella De Laurentiis took a hit with critics and the box office, although, over the years, it has acquired an inevitable cult halo.

For Villeneuve’s film, he complained to IndieWire that no one had called him, not even to serve as a consultant: “When they released the 1984 film, they used my name as part of the promotional campaign: ‘The film that Jodorowsky couldn’t make,’ they said. This time, that wasn’t the case. They don’t call me because they think I’m going to get all the publicity. But secretly, what they’re saying with that attitude is: ‘Now we’ll get to do the mammoth movie that Jodorowsky didn’t make! It’s going to be amazing! The director is a genius!’ Well no, nobody can be a genius in Hollywood. Nobody. Because it’s purely business.”

Jodorowsky turned recycling into an art when he reunited with Moebius to conceive what would be his magnum opus in comics: The Incal. Published between 1980 and 1988, it directly rescued many Dune cartoons. The publishers of the comic series ended up accusing Luc Besson of plagiarism for The Fifth Element (1997), but lost the lawsuit because Moebius had served as production designer. In any case, the comic’s imprint on that film is indisputable.

At 95-years-old, Jodorowsky seems to have made peace with the film industry. Today, he calmly contemplates how Hollywood is going to bring The Incal to the big screen under the command of Taika Waititi — director of the Oscar-winning Jojo Rabbit (2019) — well-aware that it no longer belongs to him.

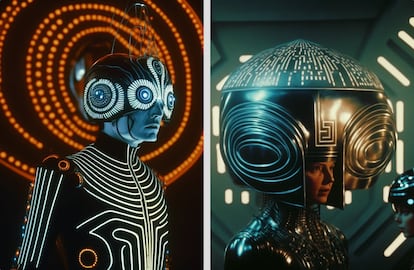

With his cultivated aura of a guru, Jodorowsky has made himself into an entire subgenre of science fiction. So much so that he has even seen what a version of Tron (1982) would have looked like under his direction (courtesy of artificial intelligence). In 2022, series director Johnny Darrell generated frames from the Disney classic on the Midjourney platform, as if it had been directed by Jodorowsky (instead of by Steven Libserger) in 1976… the same year in which his dream of making Dune faded. The result makes us wish that Jodorowsky will live to be 120, so that we can see him conjure up all the fantasies that once seemed impossible. Perhaps he can make them come true on screen.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.