‘They preferred me naked and silent’: ‘Emmanuelle,’ the erotic milestone that makes people uncomfortable 50 years later

Few films bring together so many errors of the 20th century as the adult classic starring Sylvia Kristel that after half a century has become more like a social time capsule than a redeemable movie

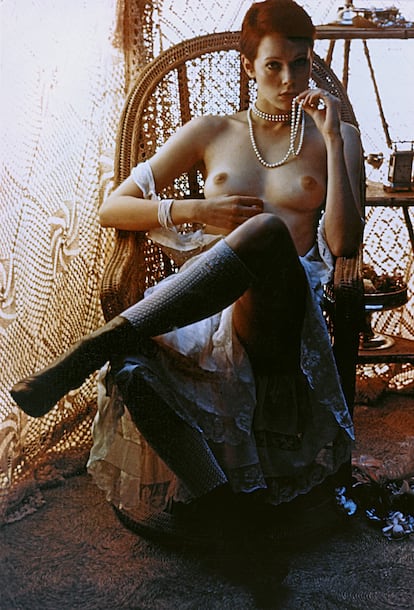

An effective starting point to delve into Emmanuelle (Just Jaeckin, 1974) is, without a doubt, its ubiquitous poster, which presents leading actress Sylvia Kristel sitting on a rattan chair, semi-nude, decorated with a string of pearls. Not only because it includes almost all the elements of the film – even if the scene never actually appears on screen – but also because each of these components is a clue to its paradoxical nature. Upon a second look, any interpretation you might reach is confronted with its opposition – just as happens with the film.

Emmanuelle shows her bare breasts over a white lace dress. She also wears thick knee-high wool stockings and lace-up ankle boots. With her hand, she absentmindedly brings the pearls close to her mouth. All of this is a way of instigating an erotic tension that is the result of other tensions, those that occur between attire and nudity, innocence and debauchery, while it also follows the codes of representation of the bourgeois. Her eyes are fixed on those of the viewer; her left leg is crossed over the right, covering her private parts. There is, therefore, a double message of incitement and impediment. All this, presented on a Filipino chair (which would become known as “Emmanuelle chair” from that moment on) that evokes an orientalizing exoticism, framed with some tropical plants in the background.

This year marks half a century since the premiere of Emmanuelle, a cultural phenomenon that reached far beyond box office success, and which has traversed various stages in critical and public appreciation. After the initial frenzy – in central Paris alone it drew more than three million spectators for a total population of about two million – it came to be considered the byproduct of a specific, surpassed juncture, but it also established itself as a manifesto of the sexual revolution, to later serve as an object of analysis from feminist perspectives.

Two years ago, the French filmmaker and critic Clélia Cohen directed the documentary Emmanuelle, la plus longue caresse du cinéma français (Emmanuelle: Queen of French Erotic Cinema), which highlighted its connection with the post-May 1968 emancipation. Shortly before, they announced the project (currently on hold) for a series about the life of Sylvia Kristel (1952-2012), the star of the original movie, which particularly resonates in the times of #MeToo, and a sort of remake, made by director Audrey Diwan – author of Happening (2021), a film about women’s right to abortion – with Noémie Merlant and Naomi Watts in its cast, will soon be released.

Feeling good without feeling bad

The Emmanuelle from 1974 narrated the erotic adventures of a young French woman in an open marriage with a diplomat, all in the context of a Thailand straight out of a lifestyle magazine. Although its sex scenes – always simulated – were nothing compared to the erotic contents that can be found on today’s streaming platforms, they were unusually explicit for the commercial cinema of the time. Up to 43 “official” features were shot under the Emmanuelle label, in addition to countless derivatives, including a Black Emmanuelle (Black Emanuelle, 1975), a nun (Sister Emanuelle, 1977) and an intergalactic one (Emmanuelle in Space, 1994).

Fifty years ago, the field had been conveniently prepared for the release of the original film. The shock wave of May 68 had brought a loosening of sexual mores that favored experimentation and the questioning of monogamy. Research on sexuality by Alfred Kinsey and Masters and Johnson had paved the way for publications such as the best-selling Open Marriage: A New Life Style, in which Nena and George O’Neill discussed the promising possibilities of non-monogamy. In France, Georges Pompidou was dead and the conservative Valéry Giscard d’Estaing had just been elected president of the French Republic, defeating the socialist Mitterrand, after luring voters – what a paradox – with the electoral promise of eliminating censorship, which generated a wave of erotic premieres of which Emmanuelle was the flagship.

Shortly before, an advance party had cleared a path: movies like Last Tango in Paris (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1972), La Grande Bouffe (1973, Marco Ferreri) and The Mother and the Whore (1973, Jean Eustache) had already incorporated libertine plot elements and realistic sex scenes in a, let’s say, prestigious context, far from the pornographic. However, their sexual content was a way to express a certain discomfort and question the prevailing institutions, while Emmanuelle reflected a carefree, hedonistic posture, intended as a spicy condiment in the stew of the bourgeois. Its slogan, “Lets you feel good without feeling bad,” was clear about its intentions.

The project was conceived by Yves Rousset-Rouard, a former notary clerk who, having recently become a film producer, was determined to debut with the adaptation of the erotic novel Emmanuelle, published in 1959 by Emmanuelle Arsan. Behind this pseudonym was Marayat Bibidh, a woman from Thai high society, the daughter of a diplomat who was married to Louis-Jacques Rollet-Andriane, a French United Nations official stationed in Bangkok. As has often been argued, the author of Emmanuelle could actually be Rollet-Andriane himself, who was an erotic literature enthusiast, or it could have been a joint effort. This was confirmed in 2016 by the Danish writer Suzanne Brøgger, a friend of the couple, in her afterword to the book La Philosophie Nue.

Revered and reviled

Another newcomer was chosen to direct the film: the young photographer Just Jaeckin, who stood out thanks to his fashion editorials, in which he displayed a refined aestheticism. According to Jaeckin, it was he who discovered Sylvia Kristel, who was auditioning for another film. At the time, Kristel was a 21-year-old Dutch model and actress, winner of the Miss TV Europe beauty pageant, dating the prominent Belgian poet and novelist Hugo Claus (two and a half decades her senior) and with a history of family estrangement and a somber episode of sexual abuse in her childhood. Her acting experience was limited, but all they wanted from her was her image and her superb anatomy, so her voice was dubbed – something that would become the norm in practically all of Kristel’s subsequent filmography, forever overshadowed by Emmanuelle.

Sylvia Kristel appeared in three other films and a television series within the Emmanuelle saga, with decreasing but still considerable success. Her best films – Alice or The Last Escapade (1977) by Claude Chabrol, La Marge (1976) by Walerian Borowczyk or René La Lanne (1977), by Francis Girod – were commercial failures, and are practically impossible to find today. Her acting skills were always questioned – although, in all fairness, she never got many opportunities to show them.

Despite her command of English, Kristel was unable to develop a career in American cinema. Apart from a few regrettable professional decisions – according to Jeremy Richey’s book Sylvia Kristel: From Emmanuelle to Chabrol (2022), she rejected roles in Bergman’s The Serpent’s Egg, David Lynch’s Dune and Blue Velvet and John Guillermin’s King Kong – her addiction to alcohol and cocaine did not help, either.

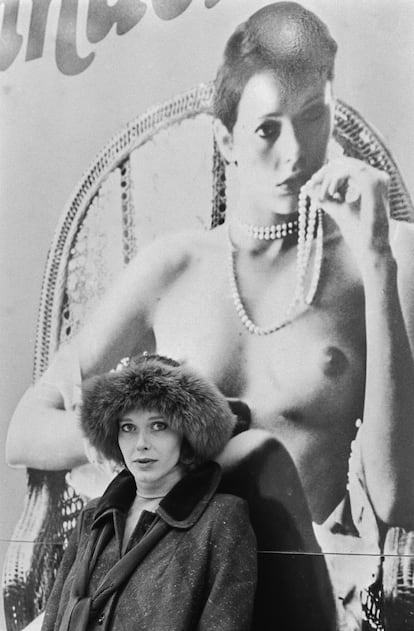

The actress died of cancer in 2012 after publishing a memoir in which she described with singular lucidity the ambivalent position in which she had been placed: that of a revered, and at the same time reviled, star. She lamented that none of her non-erotic films had attracted the audience. “I was dressed, but people preferred me naked,” she wrote. “I spoke, but they liked me better silent, or dubbed. I realized that the public had been deeply affected by Emmanuelle and wanted to prolong their fantasy, to keep me within it, symbolic and naked, idealized and necessary.”

Under the male gaze

The success of Emmanuelle exceeded all expectations. Fifty million people went to see it in its long international premiere. The movie ran for more than 10 years at the Le Triomphe cinema on the Champs-Élysées in Paris. Its scandalous scent swept the world, even if it came from a product that was in fact quite conservative, subject to the bourgeois and patriarchal notions of its time. Emmanuelle engages in a series of extramarital affairs, including orgies and sex with strangers, but almost always supervised or observed by men. The way in which nudity – almost always female – and sexual encounters are filmed does not deviate for a second from what the feminist critic Laura Mulvey had called “the male gaze” in her famous essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, written a year before the premiere of Emmanuelle and published a year later.

“The 1970s saw the birth of feminist film theories,” says Violeta Kovacsics, film critic and professor at the Higher School of Cinema and Audiovisuals of Catalonia. “I think that in this case it is interesting to keep in mind Laura Mulvey’s book, which articulates a critique of the male gaze based on the Freudian notion of scopophilia, the pleasure of looking, quite applicable in erotic cinema. But, in addition, Mulvey detects a mechanism by which the gazes of the male characters converge, which are both that of the director and that of the viewer. That is the male gaze: that of everyone who observes that female body.”

The same principles operate in everything that concerns homosexuality. Emmanuelle seeks pleasure in the bodies of other women, such as her friend Bee (played by Marika Green) and the young Marie-Ange (Christine Boisson, who was barely 18 years old at the time and who would later say that she also suffered sexual violence during childhood). But more than supporting the hypothesis of a lesbian Emmanuelle, these episodes serve, again, as a performance put on for the benefit of the male gaze. “These types of lesbian scenes seen from the perspective of a male voyeur are very typical of the sexploitation cinema of the 1970s, and have impacted the representation of lesbianism in film until today,” adds Francina Ribes, doctor in media and culture from the Autonomous University of Barcelona and author of the book Ausencia y exceso: Lesbianas y bisexuales asesinas en el cine de Hollywood (Absence and excess: Killer lesbians and bisexuals in Hollywood cinema). “In fact, the area of popular culture in which lesbianism has been most represented is pornography, always from that androcentric perspective and for the enjoyment of men. This doesn’t mean that lesbian and bisexual women haven’t often appropriated these representations, partly due to the lack of other references and partly because, in some cases, these images open new horizons and can have an iconographic force that goes beyond the intention with which they were created.”

Fetishizing colonialism

The colonialist implications of the saga, which tended to seek exotic locations in which the locals were limited to being in the background, playing the passive role of instruments of pleasure or being uncontrollably sexual savages, have been studied less. Starting with the first film, shot in Thailand, the only country in the Southeast Asian region that has never been a European colony (colonialism without a colony), and which at that time was going through a democratic period between two dictatorships. In one of the final scenes, Emmanuelle, visiting a Thai boxing ring, offers herself as a trophy to the winner and excitedly licks the sweat that drips from his forehead, in what is nothing more than the fetishization of an exoticized body.

Two years later, In the Realm of the Senses (1976) would be released, a masterpiece by Japanese director Nagisa Osima about the intersections between desire and death. Due to its complexity and its non-complacent approach to eroticism, its shocking scenes of unsimulated sex and the fact that it was directed by an oriental author, it could be interpreted as the exact opposite of Emmanuelle.

With all its contradictions, it is difficult to see in Emmanuelle anything more than an artifact intended to reinforce the bourgeois status quo from a vague appearance of transgression. It is worth remembering that, in the middle of the 19th century, a supposedly much more modest novel, Madame Bovary, by Gustave Flaubert, triggered a judicial process for outrage to public and religious morality and good customs – in other words, to the basic principles of bourgeois institutions. More than a century later, an adaptation of Madame Bovary was precisely the project that Sylvia Kristel tried to bring to the screen in an attempt to escape her typecasting as Emmanuelle. She never succeeded.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.