‘Architecture porn’: When the most obscene thing in a movie is a palace

‘Saltburn’ is the latest example of what social media calls ‘house porn.’ That is, when what is truly sinful in a supposedly transgressive film is not the sex scenes but a house with 85 rooms and a garden with a maze

Try entering the hashtag #houseporn in your go-to social media. What you will get is not pornography, or not what is conventionally understood as such, but a succession of images of houses from different periods and styles, which appeal to both the eye and the greed of the viewer. A similar principle has been followed in Saltburn, the recent film by Emerald Fennell, which has caused a lot of talk for its nudity and calculatedly bizarre sex scenes, but also for the real estate that gives the movie its title. Saltburn mansion is actually Drayton House, in the English county of Northampstonshire.

What is truly pornographic about the film is the way the house is filmed, how the camera recreates its opulent interiors and the scenic beauty of its façade. This choice of staging is not entirely arbitrary, since for the protagonist (played by Barry Keoghan), a fraud consumed by intense social resentment, the house is the authentic object of desire, and sex is only one of the tools he uses to obtain it. But Saltburn is not the only film that has followed this strategy. In fact, on some occasions, the eroticism of the story has been overshadowed by the eroticism of its setting. There are artistically irrelevant films of which the only thing worth remembering is their beautiful locations, but also some masterpieces where houses are successfully used to set the tone and reflect the psychology of the characters. Here are some notable cases.

L’inhumaine (1924), by Marcel L’Herbier

The least eccentric thing about this little-known gem, the apotheosis of art deco, is not that an opera singer (Georgette Leblanc) starred in a silent film, or that its plot was a melodrama with elements of science fiction. It was the houses in which the action is set. In them, cubist designs were reproduced by the young architect Robert Mallet-Stevens, who would become one of the greats of Modernism. The audience was speechless, although they were also divided between those who hated the film and those who defended it as an avant-garde work. Painter Fernand Léger and future directors Claude Autant-Lara and Alfredo Cavalcanti also collaborated on the mind-blowing set designs. It couldn’t be more modern in 1924.

The Rules of the Game (1939), by Jean Renoir

After a muted reception at the time, this masterpiece of French cinema has, for decades, made consistent appearances on all the best films in history lists. Renoir painted a corrosive portrait of the high bourgeoisie in which the decorations had to faithfully reflect all the opulence of this social class. Highlights include the luxurious apartment of the attractive marchioness Christine de la Chesnaye (Nora Gregor) and the château in which the entire second half takes place, with its enormous expanses of checkerboard flooring. “It is the film of films,” François Truffaut said of it.

Mon Oncle (1958), by Jacques Tati

Tati decided to set his third film as a director in a futuristic house with a lot of glass, designer furniture, proto-home automation technology, and unexpected mechanisms that give rise to the most hilarious visual gags. It also contrasted with the old buildings of the Parisian neighborhood in which Monsieur Hulot was able to cope better than in the coldness of high-tech. In its day, the film was therefore branded as reactionary, but that does not cloud its merits.

What? (1972), by Roman Polanski

Fresh from the success of Rosemary’s Baby and the failure of Macbeth, Polanski decided to undertake a modern, spicy adaptation of Alice in Wonderland. The result is one of his worst films, which at times seems like he made it made solely to show off American actress Sydne Rome’s body. That much is undeniable. Just as it is also true that the house in which it is filmed, a villa on the Amalfi Coast, is a feast for the eyes. The property, like the works of art that appear in it, belonged to the film’s producer Carlo Ponti, the husband of Sophia Loren.

Conversation Piece (1974) and The Leopard (1963), by Luchino Visconti

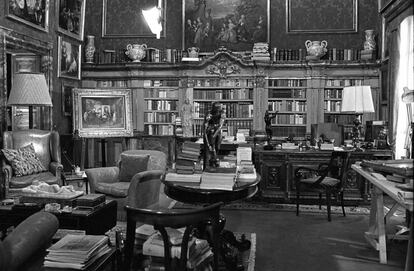

Rarely has a universe been recreated with such accuracy and evocative capacity as Visconti did in The Leopard. The long dance sequence in a Sicilian palace during the Risorgimento was filmed in the authentic Palazzo Valguarnera-Gangi in Palermo, a marvel of the late Baroque. A decade later, Visconti returned to have the same star, Burt Lancaster, who played a character inspired by the writer and art critic Mario Praz in Conversation Piece. Praz is the author of The House of Life, a 1964 essay that is in itself the Old Testament of #houseporn. In shot after shot, the cluttered interiors of the old Roman palazzo where the film’s solitary professor lives contain so much information that the human eye is unable to register it all. The big surprise comes when we are shown the impressive terrace overlooking Rome’s rooftops and domes, which the dark character played by Silvana Mangano understandably covets.

Cries and Whispers (1972) and Fanny and Alexander (1982), by Ingmar Bergman

As Bergman explained, the red walls of the house in which the sister of Cries and Whispers lived represented a maternal womb. Everything that happened there was in an indefinite space between sleep and wakefulness, between life and death, the realistic and the abstract. Later, in Fanny and Alexander, with the help of set designer Anna Asp, Bergman uses the warm bourgeois interior of the family home in which the family celebrates one of the most memorable Christmases in cinema to contrast with the icy austerity of the stepfather’s house.

Interiors (1978), by Woody Allen

The interiors of the title refer both to the tortured psyches of the protagonists (three sisters and their mother) and to the professional activity of the latter, a decorator with a special love for gray and cream tones, matching her limited ability to show affection. All of this can also be understood as a metaphor for directing a film, in a self-referential nod on the part of Woody Allen. Its sophistication marks the highest point of the New York director’s interest in interior design, which can also be seen in the apartments of Hannah and Her Sisters, Alice, and Husbands and Wives, among many others. When he moved to Paris, in the case of the recent Coup de Chance, the level of taste did not decline.

9 ½ Weeks (1986), by Adrian Lyne

With its advertising aesthetic and its decaffeinated masochism, what is perhaps the most famous erotic drama of the eighties today stands out above all for the brave acting on the part of Kim Basinger and for the Manhattan penthouse of Mickey Rourke’s character where much of the action takes place. It is a careful representation of the yuppie universe that was in vogue at that time: glass walls, monochromatic accents, and furniture signed by Breuer, Meier, and Mackintosh. The vibe is less cozy than sexy.

Brideshead Revisited, television series (1981) by Charles Sturridge and Michael Lindsay-Hogg and film (2008), by Julian Jarrold

Both adaptations of Evelyn Waugh’s novel about a family of British Catholic aristocrats and their struggles with faith and divine grace were both filmed at Castle Howard in North Yorkshire (U.K.). These are two typical examples of British academicism, with first-class performers (Jeremy Irons, Laurence Olivier, and John Gielgud were in the series, and Emma Thompson and Matthew Goode in the film) and perfect setting, but with somewhat faint staging. Repressed homosexuality (or plain old sexuality) due to social and religious demands becomes the highlight of the menu. It does not seem risky to say that Saltburn has borrowed a few elements from its plot and characters. For the rest, Brideshead (that is, Castle Howard) has gone down in history as the quintessential British mansion.

Dangerous Liaisons (1988), by Stephen Frears

Another adaptation of a literary classic, this time from the epistolary novel written in the 18th century by Choderlos de Laclos (in turn adapted for the theater by Christopher Hampton). Set a few years before the French Revolution, when the country’s nobles did not seem to harbor more concerns than erotic ones, the brief plot of sexual conquests and revenge unfolds in a variety of neoclassical and rococo châteaux and hôtels particuliers. Parquet floors creak deliciously and the crystal of the chandeliers tinkles when they are moved by the servants.

Howards End (1992) and The Remains of the Day (1993), by James Ivory

James Ivory filmed two of his best works in the first half of the nineties, adapting E.M. Forster’s Howards End and Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day, both with casts led by Emma Thompson and Anthony Hopkins. Once again, the concepts of period cinema and high quality come together to offer sumptuous settings with a 100% British seal. In the first instance, the eponymous country house is once again the center of a tangle of intrigues, deceptions, and unsatisfied desires. In the second, the stately mansion in which the protagonists work as servants is both a way of life and a prison that frustrates all aspirations for happiness.

I Am Love (2009) and Call Me by Your Name (2017), by Luca Guadagnino

Luca Guadagnino is addicted to houseporn, to the point that some have called it “decorative.” His entire filmography reveals an evident appreciation for interior design, and he has even made his professional debut in that area. Perhaps the two films of his in which this is most evident are I Am Love, filmed in the Milanese art deco monument of Villa Necchi Campiglio, and Call Me by Your Name, which takes place in Villa Albergoni, a 16th-century country house in the province of Cremona. Faced with this truly staged hardcore porn, the supposed passions that in theory occupy the center of both works are somewhat muted.

The Handmaiden (2016), by Park Chan-wook

It must be noted that, in this case, everything was at the same level: the carnal lewdness does not detract from the decorative in this thriller crammed with plot twists. The story is set in Japanese occupied Korea before World War II, in a palatial residence that mixes Japanese and English styles. In reality, it is a house designed at the beginning of the 20th century by the influential British architect Josiah Conder and is located in Japan. However, most of the interiors were built in a studio. It is especially difficult to forget the immense library in which the lead character stages her erotic literature sessions.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.