Mickey Mouse is free at last (from copyright)

The earliest version of Walt Disney’s most famous creation, which appeared in an animated short in 1928, enters the public domain in the United States

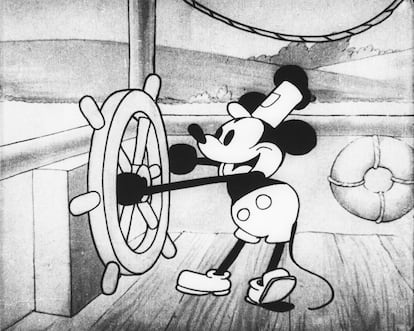

Those in charge of the Disney archive say that in 1930 a man waited for Walt Disney outside a hotel in Los Angeles to propose a deal. The man was willing to offer Disney $300 in cash if he would let him reproduce a drawing of his on the covers of some notebooks. The caricature he was interested in was that of a mouse that had appeared a couple of years earlier in the animated short Steamboat Willie, directed by Disney and Ub Iwerks. Disney, who was a little short on cash at the time, immediately said yes. It was the beginning of the commercial exploitation of Mickey Mouse, a character that has appeared in countless products over several generations. As of January 1, 2024, the most famous rodent in the world is part of the public domain.

The earliest form of Mickey Mouse loses copyright protection in the United States in 2024, when the cartoon, which debuted in that 1928 short where the mouse pilots a steamboat and whistles a tune from 1910, entered the public domain. This annual selection of works, known as Public Domain Day, is compiled by Jennifer Jenkins, a professor of law and director of Duke’s Center for the Study of Public Domain. The list of works losing copyright protection this January, after 95 years, is especially powerful.

They are works, films and songs published in 1928 (and some sound recordings from 1923). Also entering the public domain alongside early Mickey are Lady Chatterley’s Lover, by D. H. Lawrence; Orlando, by Virginia Woolf, and The Threepenny Opera, by Bertolt Brecht, among others. The list also includes films by Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, the last silent film that Harold Lloyd shot and The Passion of Joan of Arc, by Carl Theodor Dreyer, considered one of the early masterpieces of cinema.

Steamboat Willie was the third work to feature Mickey and Minnie, but it was the first to be publicly exhibited. Another of those shorts is Plane Crazy. Disney, as he himself explained, was inspired by performances by stars of the time such as Douglas Fairbanks and Charlie Chaplin to create the mouse character. The short’s title was borrowed from Steamboat Bill, a Buster Keaton film (which has been in the public domain for 67 years).

The mouse occupies the most prominent position among the cultural products that will be released from copyright in 2024 in the United States. The Disney company has maintained a court battle for decades to retain copyright and the benefits that come with it. “What Disney has always done is reuse the public domain to enclose it again,” says Ignasi Labastida, one of the leaders of the Creative Commons organization, dedicated to promoting access and cultural exchange.

An example is the 2016 version of The Jungle Book, a film that emerges from the 1957 original and this, in turn, from a collection of stories by Rudyard Kipling that lost copyright in 2011. The same thing happened with Frozen, inspired by a story by Hans Christian Andersen; Fantasy, which draws on a poem by Goethe, or The Lion King, inspired by Hamlet by Shakespeare. Not to mention The Little Mermaid, Cinderella or Pinocchio. “By making a derivative work, it generates new rights, but now it is clear that these cannot be extended infinitely,” says Labastida.

Disney doesn’t just use great works of literature as a creative source. The company is also one of the most active actors in defending the rights of its creations. “Its role has been critical in the lobby battle that extended copyright protections in 1976 and then in 1998,” writes science fiction author and digital activist Cory Doctorow. The legislation approved in Congress in 1998, proposed by the singer Sonny Bono, who became a legislator, prevented the passage of works into the public domain for another 20 years, setting the period of rights at 95 years. There are some experts who call this law the Mickey Mouse Act, although this may be an exaggeration according to Jenkins (because there were other agents who pushed for its approval).

With this law, Mickey Mouse gained time under copyright protection. It loses it now, but only in the United States. “2024 is a symbolic year,” Jenkins writes. “The love triangle between Mickey, Disney and the public domain is about to evolve and may even be resolved in real time.” In the European Union, the law says that copyrights expire 70 years after the death of the creator of the work, meaning that Europeans will have to wait until 2036 to see Walt Disney’s creations released.

Starting this year, anyone who wishes can use the drawing of Steamboat Willie to copy it, share it, adapt it or make additions to it. But it is still a trademark, so it cannot be used to link a third-party product to Disney.

“More modern versions of Mickey have not been affected by the expiration of the Steamboat Willie copyright, and Mickey will continue to serve as a global ambassador for our company and in our narrative, amusement parks and in our merchandise,” the company said in a statement to the Associated Press agency. This means that the versions that appear in Fantasia or in the successive television series that the network has developed continue to have copyright. The company assures that “it will work to prevent confusion due to the unauthorized use of Mickey and other iconic characters.”

Neverland

In addition to Mickey, another beloved childhood character is making his Public Domain Day debut. It’s Peter Pan, the boy who refuses to grow up in Neverland. The character was created by the Scottish author J. M. Barrie and his case helps to understand how capricious and problematic the subject of copyright can be in a globalized world. The work loses its protection in the United States in 2024, despite the fact that the play has been performed since 1904 and the novel appeared in 1911.

Peter Pan now appears on the list because it was first published in its entirety in 1928. In the United Kingdom, however, the story is very different. Shortly after the play’s release, Barrie gifted the rights to the Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital. Since then it has been the main form of financing for the center, which collects royalties from the books, films and plays of the original work.

The rights expired in 1978, but the then-Prime Minister, James Callaghan, proposed a rule to extend protection of the novel in perpetuity. With the harmonization of laws that the EU brought, Peter Pan became a problem. So the rest of Europe adopted the 70 years since Barrie’s death, while in the U.K. the hospital remains the beneficiary.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.