Keytruda: The drug that makes as much money as Zara and has sparked debate over patent lifespans

MSD’s monoclonal antibody, indicated for 15 types of cancer, smashed industry records with sales of $27.3 billion in 2024, with six years of monopoly remaining

The recent publication of the 2024 results of the multinational Merck, which operates as Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD) outside the United States, has revealed an unprecedented figure in the history of the pharmaceutical industry. Sales of the drug Keytruda, a monoclonal antibody indicated for several types of cancer, reached $29.5 billion after growing 18% last year. Never before has a drug reached such levels, shattering the record — once considered unattainable — of $19.95 billion set by Abbvie’s Humira in 2022. To put the figure into context, Keytruda has a turnover as high as the fashion giant Zara or the gross domestic product (GDP) of countries such as Senegal and Iceland.

“It’s a drug that has forced us to rethink how we fund some treatments in the public health system. The system wasn’t prepared for a therapy that could reach this magnitude,” says Sandra Flores, a member of the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (SEFH) and head of this service at Virgen del Rocío Hospital in Seville. One of the keys to the success of pembrolizumab — the name of the active ingredient in Keytruda — is its ability to act against various tumors. This has led the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to approve 30 indications for 15 types of cancer, 18 of which are currently funded by the public health system.

And although it may be surprising today, there was a time at the beginning of the last decade when the molecule was almost thrown in the trash. When Merck bought the pharmaceutical company Schering-Plough in 2009 to acquire therapies such as ezetimibe, indicated for cholesterol, it also casually acquired other drugs pending development, such as pembrolizumab, which had come into Schering-Plough’s hands two years earlier when it acquired another company, Organon BioSciences. According to Forbes in 2017, the drug was so low on Merck’s priority list that the company included it on a list of discarded molecules it was going to try to market.

“What happened then was a coincidence that, looking back, seems very striking. BMS [another pharmaceutical company] published encouraging results for two similar antibodies, ipilimumab and nivolumab [later marketed under the brand names Yervoy and Opdivo], and Merck realized that pembrolizumab might, after all, have some potential,” explains Josep Tabernero, director of the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology in Barcelona.

Gregory J. Carven was one of the drug’s inventors at Organon, and he explains another paradox in the drug’s history. “Our program was actually focused on autoimmune diseases, like arthritis, not cancer. We wanted to reduce inflammation and the immune system response in these patients,” he wrote to EL PAÍS. In reality, he admits, they ended up discovering the opposite: “We found antibodies that increased immune responses, so we changed our target and focused on cancer,” the researcher explains.

Immunotherapy has revolutionized oncology over the past 15 years, but the first steps weren't easy. "A major challenge was the general climate surrounding these drugs at the time. Before the success of PD-1, most of the industry wasn't interested in harnessing the immune system against cancer due to previous failures of other drugs," Carven recalls.

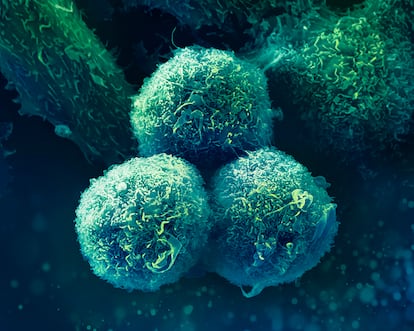

PD-1 is a protein found on the surface of the immune system’s T cells. Activating it serves to boost the immune response against cancer cells, but these cells have another protein, PDL-1, which binds to it and acts as a brake, allowing the tumor to evade the body’s defenses. “Pembrolizumab prevents the two proteins from interacting, which allows the immune system to continue recognizing malignant cells and attacking them,” Tabernero says.

Merck believes the drug still has a long way to go, according to a spokesperson. “Pembrolizumab has redefined the treatment of certain cancers, and we look forward to further innovation for patients in the coming years. We currently have the industry's largest immuno-oncology clinical research program, with more than 1,600 trials studying pembrolizumab across a wide variety of cancer types and treatment settings.”

In 2010, however, the company encountered a seemingly insurmountable problem: the years-long delay it had accumulated with respect to BMS and its research on ipilimumab and nivolumab. This led Merck to adopt a revolutionary approach to drug development, including more than 1,300 patients with different types of cancer in Phase 1, whereas this typically includes only a few patients to test the safety of the molecules. “It was the largest Phase 1 trial ever conducted in oncology,” Catalan researcher Antoni Ribas, who played a key role in those early phases, told Forbes.

The positive results led the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to approve Keytruda for advanced melanoma in 2014 (the EMA did so in Europe in 2015). But Merck's strategy has allowed the company to expand the number of approved indications, which has become a challenge for healthcare systems like Spain's.

“The law establishes that the initial price agreed between the Ministry of Health and pharmaceutical companies for the first indication must be gradually reduced if new indications are approved, as the number of units purchased increases. The problem is that this system has ended up being impractical with so many indications. In some cases, it could even be perverse, since some were intended for so few patients that the company might not be interested in ordering them if this would lower the price of all of them. We can say that Keytruda is the first drug for which the Spanish model has not worked, and we have had to rethink how to resolve some situations,” says Flores.

Keytruda sales have been growing at a rate of nearly 20% annually since 2020. This trend predicts revenues exceeding €200 billion ($217 billion) by 2031, the year in which patents expire in Europe (in the United States, they will expire in 2036). Initially, however, these patents were scheduled to expire in the EU in June 2028, but Merck has managed to delay them by resorting to an instrument called a supplementary protection certificate (SPC). This has led many experts to warn of the enormous profits that blockbuster drugs like Keytruda have been making for years at the expense of healthcare systems.

Bernabé Zea, founding partner of the specialized consulting firm ZBM Patents and Trademark, explains that SPCs were created to "compensate" for the lengthy drug development processes: "Patents protect any invention for 20 years. But, for example, you can put a stapler on sale very soon after patenting it, while a drug cannot be sold for the first decade because that's when you're undergoing clinical trials and regulatory procedures to validate its safety and efficacy. The certificates were created to guarantee a sufficiently long period of exclusivity to be attractive to the industry and incentivize research."

In the case of Keytruda, the SPCs have allowed the monopoly to be extended for two years, from June 2028 to July 2030, plus a six-month extension — until January 2031 — through the so-called pediatric extension, another mechanism intended to incentivize research in this field in exchange for extending the patents. Laura Vallejo Torres, a professor at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and a member of the Spanish Health Economics Association (AES), believes that the first extension is not justified for blockbuster drugs like Keytruda if another variable is taken into account: price.

“The success of the drug should be an incentive for innovation for Merck and other companies, but this cannot be at the expense of the sustainability of healthcare systems through high prices, which, moreover, are not always justified in relation to the health improvements they bring,” she argues. In this expert’s opinion, the emergence of biosimilars — the equivalent of generics for these types of biological drugs — “is essential for the sustainability of the system and to guarantee patients access to future innovation.” Each vial of Keytruda has an official price of €3,566 in Europe ($3,871), an amount subject to confidential discounts. As the drug is administered in doses of 200 or 400 milligrams every three to six weeks, the annual cost per patient can amount to several tens of thousands of euros.

For Zea, the problem for competition lies not so much in SPCs but in other strategies. “One of them is the so-called patent networks. The original, which is the true innovation, is the one that expires first. Therefore, companies try to delay competition by requesting other patents related to secondary aspects, such as formulations, indications, etc., which are often of dubious validity and aim to extend exclusivity. Another strategy is to introduce more or less significant changes to the drug to patent the new version. In the case of Keytruda, Merck is promoting the subcutaneous version [the current one is intravenous]. If it manages to convince the medical community that this version is more convenient than the current one, it will de facto manage to extend the monopoly for many more years,” says this expert.

According to information available on the website of the Spanish Association of Biosimilar Medicines (BioSim), there are currently 10 companies developing a pembrolizumab biosimilar. Encarna Cruz, the organization’s general director, warns, however, that this is not the norm and that in almost half of cases, a biosimilar is not ready when the original drug’s patent expires. “Developing a biosimilar takes six to eight years and requires an investment of €100 to €300 million.”

It’s an investment not without uncertainty: first, because the launch date is often delayed by a complex network of overlapping patents. Keytruda, for example, has 129 different ones in the U.S. alone. And second, because new versions of the original are often marketed shortly before the biosimilar appears — in this case, the subcutaneous version of Keytruda. “This can mean that by the time the biosimilar has been developed, the market in which it competes simply no longer exists because all consumption has shifted to the new versions,” Cruz concludes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.