‘Something in this industry makes people sick’: why music fails to make a clean break with drugs and alcohol

In music critic Ian Windwood’s latest book, ‘Bodies: Life and Death in Music,’ he analyzes a problem that, until not too long ago, was perceived as a romantic legend: drugs and rock ‘n’ roll

Sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll: as with all clichés, it’s almost impossible to write about it without blushing. This expression — originally used in a song by the British rocker Ian Dury — sums up one of the most powerful and fertile myths of popular culture. A myth that has provided countless hours of speculation to fans for years and thousands of pages in the social and cultural chronicles. It’s been well cultivated in literature as well, starting with a famous story by the Argentine writer Julio Cortázar called The Pursuer (1959), based on the disorderly, bohemian life of Charlie Parker.

Everyone is familiar with the image of a cursed poet or musician, who has a tormented existence: staying up late, drinking and taking drugs. They peer into abysses that others, the consumers of art, cannot even imagine. The audience offers them their money, their admiration and their affection during the performance. It seems like a fair deal... except for those who fall by the wayside.

Fortunately, in recent years, concerns about mental health are appearing in all industries, including the music sector. All those suicides and premature deaths that, until now, were considered to have been isolated incidents or tragic legends were actually indicative of something happening to those who go on tour. Beyond the creative anguish and revelry that afflicts artists, metal health problems are also particularly common among those who work around them: technicians, managers, press, editors, drivers…

According to a study carried out in 2021 in the United Kingdom, someone whose work is related to music is three times more likely to develop depression and four times more likely to experience anxiety than if they were dedicated to any other activity. “There’s something systematically wrong in the world of music and it makes people sick.” This is the thesis of Ian Winwood, a journalist with decades of experience covering bands such as Metallica. He is the author of Bodies: Life and Death in Music, a chronicle about how the music industry “tolerates and encourages behaviors unthinkable in any other type of job.”

Drugs are the tip of the iceberg

Winwood isn’t alone. In recent years, more and more British organizations are concerned about the issue. Groups such as the MITC (Music Industry Therapist Collective) have emerged, made up of psychologists who specialize in the problems of musical professionals and their environment. The MITC recently published Touring and Mental Health, a detailed manual full of practical advice and scientific information.

“We all — whether or not we work in the music industry — have certain possibilities of developing anxiety disorders, personality disorders, addictions, depression... there’s a tendency or a genetic predisposition. But in this industry, we don’t sleep, people are partying all around you, there’s fear and there are traumatic events, so it’s easier to develop [issues],” explains Rosana Corbacho, a Spanish psychologist who collaborates with the MITC. Corbacho decided to study psychology while working in the music industry in London, because she realized that those around her “had recurring problems.”

“I got the impression that, when they went to therapy, their therapists didn’t understand how important their profession was to them. These specific problems are, for example, creative blocks, anxiety attacks, difficulties in the relationship between band members or with managers... it’s often assumed that the only problem musicians have is that they consume drugs. However, something much more complex is at play, because while the substances are present, they’re often the consequences of what someone is suffering from.”

Joan Vich, a former festival director, recently published a chronicle of his 25 years of work in the music field. He discussed how drug dealers were a frequent presence at these festivals, to supply artists with what they required. This is confirmed by Marcela San Martín, who used to work at major music events across Spain. She’s the founder of the Association of Women in the Music Industry (MIM).

“At festivals,” she recalls, “we would be given the dealer’s phone number directly. A musician even threatened to cancel a sold-out concert if we didn’t bring him his corresponding grams. I walked away, leaving him to fight with his road manager.”

Rafa Gómez, a concert promoter, also found himself in similar situations: “I won’t name names, but I remember having to go walking on a rainy Sunday in Torrelavega (Spain) to look for a [dealer], because the artist said he wouldn’t show up otherwise. I told him okay, I was going. After half-an-hour I came back soaked: I had torn my pants and shirt a little and I invented a lie that I had nothing, because I had been mugged.” In any case, Gómez clarifies that “today, it’s not common for musicians or technicians to be intoxicated during their performance. Everything happens punctually and is taken care of, because both artists and technicians have a team behind them that supports them.”

“The most intense excesses cannot be maintained for a long time. Not even the most famous bands had a very long journey,” Corbacho notes. “In the end, either you retire or something happens to you. You may have put out a great album, but that productive rhythm cannot be maintained. To create, you need to rest, eat well, have interpersonal relationships… it’s a very demanding life, which requires a lot of work.”

So, while hard drugs sometimes aggravate problems, they may not be as common as we think. And, almost always, they’re handled with a certain amount of self-control… a virtue that, according to Víctor Coyote (a legendary musician since the 1980s) is “essential in the artistic world, because the function of the seller has been delegated to the artist. Every musician has to promote themselves in an exaggerated way nowadays: there isn’t enough time to rehearse, keep track of social media and get high.”

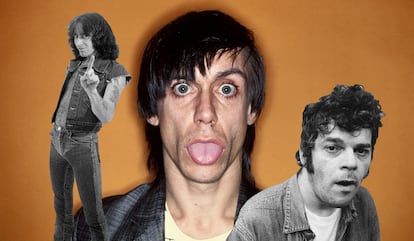

The myth of endless parties also seems to have come to an end. Coyote clarifies: “I was a supporter of the diet that Iggy Pop had: [drugs] at night and gym in the morning. It’s a radical diet that I never strictly followed, but it seemed fine to me. But of course, after two days of partying, I was already sick to death of putting up with the pain and putting up with myself. I wanted to get up early again to start [working].”

Alcohol consumption — despite having directly or indirectly caused the deaths of artists such as Bon Scott, John Bonham or Dolores O’Riordan — is considered to be very different from drug abuse. It’s much more structural and socially acceptable. “I’ve been in many dressing rooms where you can get all the beer you want long before a piece of fruit or something to eat is offered,” recalls Javier Carrasco, a member of several bands on the Madrid scene. “Alcohol is a deeply-rooted, tolerated and even naturalized cultural habit,” San Martín adds. “It’s practically impossible to imagine a concert hall without alcohol. The venues live on consumption in bars — not on [ticket sales] — and those of us who dedicate ourselves to programming know that we have to work with groups whose audiences consume [a lot], regardless of the musical quality.”

Self-exploitation and fear: what substances mask

“There are two moments of risk regarding the appearance of addictions,” warns Corbacho. “When a lot of success comes suddenly — because, if there was previous consumption, one may [increase this] to anesthetize emotions resulting from pressure — and when someone who was very famous suddenly begins to have less professional activity. However, when there’s sustained success, the musician is aware that to stay [at that level], he must lead a balanced life.” In any case, the psychologist insists that “alcohol or drug abuse is a warning sign and a symptom that indicates that there are other [underlying] disorders.”

Especially since the 1990s, there have been many songs — such as This is Hardcore by Pulp, or Into the Great Wide Open by Tom Petty — about how disappointing it is to achieve the money and fame that one had fantasized so much about. This has also grown within the hip hop genre, where artists appear to maintain an ambiguous relationship with their own success, which seems like a curse. “Capitalism has triumphed… [it] permeates all strata of society and culture,” Carrasco opines. “Music is increasingly imbued with a competitive spirit that isn’t good. The two key words are self-exploitation and frustration.”

According to Winwood in Bodies, in the world of music “the chain of command is very confusing.” But this doesn’t prevent musicians from feeling exploited and squeezed to the max. As in the rest of the cultural industries, they’re almost always the ones who impose these exhausting working conditions on themselves. “Throughout the industry, there’s a tendency to push limits. Neither the musicians nor the managers take care of themselves. Relationships of codependency are created, which become harmful,” Corbacho says.

Opportunities are always double-edged swords and “oftentimes, they’re embraced from the fear of [success] ending. There’s also guilt,” the therapist adds, “when you have success and you’re not enjoying it. You’ve given your all and when you finally are where you wanted to be, you’re not enjoying it, either because of nerves, or because you compare yourself with the previous band, or because of fatigue.”

Of course, the opposite case is more common. Carrasco says that “it’s very frustrating to see very talented people who work until they burst and don’t make it.” This makes it practically unthinkable for many struggling musicians to reject a job. “The reward system for creative work is treacherous,” Carrasco continues. “We have a voracious attitude, like dogs, who eat and get stuffed because they think they won’t eat again for a week. Sometimes, we feel bad for accepting more work than we can handle… and other times, we suffer upon realizing that there’s a ceiling that cannot be broken.”

In a world dominated by streaming platforms in which authors barely receive royalties anymore, musicians have to tour almost perpetually. This is one of the biggest risks to their integrity. “In the case of big tours, we’re talking about teams of more than 200 people under enormous pressure because — although it’s a cliché — the show must go on, no matter what,” Corbacho sighs. It’s within this context that the psychologist and therapist perceives the greatest contrast between the experience of the public and that of the artists: “The public relates to the artist through a final product that provokes emotions. They often confuse their own emotions with what the artist is feeling — the artist who has done a lot of [behind the scenes] work before going on stage. There’s a disconnect, because I know that even the concerts that are perceived as great successes have [resulted in] several traumatic moments for the performer, which later have to be addressed in therapy.”

Ian Winwood decided to write his book after realizing that what he thought was merely a series of isolated incidents — such as the disappearance of Richey Edwards, or the death of Amy Winehouse — was, in reality, something much deeper. The tragedies suffered have revealed a widespread phenomenon that is often misunderstood, or is approached through romanticism and mythomania. “Romanticism is very bad, very heavy. It ends when you realize that you’re actually working in the hospitality industry,” Víctor Coyote concludes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.