Hip hop turns 50: From the Bronx to a demand for big brands

The genre — born in the New York borough — celebrates its consecration as a global cultural phenomenon that has reinvented itself since its inception

“When New York flushed, the shit came out through the Bronx,” recalls Paradise Gray, referring to the borough where hip hop was born, on August 11, 1973. At 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, to be precise, where Clive Campbell — later known as DJ Kool Herc — hosted a party in the projects.

The genre — which is now a multi-billion-dollar industry, having conquered luxury brands and art galleries — still doesn’t want to disassociate itself from where it came from: a place that “seemed like a war zone, with crime, drugs, segregation, poverty,” as described by Rocky Bucano, the executive director of the Universal Hip Hop Museum, which is located less than two miles from Sedgwick Avenue. Gray — the museum’s chief curator — says that this kind of music was “the CNN of the ghetto.”

Today, prominent designers and auction houses — such as Sotheby’s, which has just held its third monographic sale — flirt with the global movement like few others. While hip hop is rooted in the Bronx, it has become universal. Chameleonic in its temporal and spatial transformation, it has moved everywhere, from the Bronx to Guyana, from Europe to Asia, acquiring its own characteristics wherever it finds a foothold, without losing its essence. “Ethnic groups, languages, demographic groups, genders: everything has been assimilated, each country has made it their own,” Bucano notes.

The genre’s contemporary status as a label for certain luxury brands “is a big change, because hip hop has always been — and still is — a youth movement on the street. It has now been commercialized and many companies have invested, be it in sneakers, sweatshirts, or even car companies, such as Mercedes and BMW. You can’t go anywhere without seeing how it’s been marketed. Art that started from a very popular type of experience — that of the street — is now in shop windows all over the world. And it’s part of the agenda of the great galleries. But at the beginning it was a genre against art as an institution,” Bucano explains.

The two interlocutors know what they’re talking about. “All of us who work in the museum have done everything. We all DJ, rap, dance, paint graffiti. I’ve practiced all modalities of hip hop, I’ve also written in specialized magazines and I own a recording studio,” Gray says. The curator has published No Half Steppin’: An Oral and Pictorial History of Hip-Hop’s Golden Era. For a time, he also ran the Latin Quarter nightclub in Manhattan, which he transformed into a historic venue, the incubator of hip hop’s golden age. This ability to metabolize everything it touches is another of the genre’s characteristics: it has colonized almost everything (artistically speaking) in the last 50 years, along with aesthetics: hip hop artists and designers have influenced the fashion and body languages of millions of people around the world.

Gray was the producer for the “world famous” rap group X-Clan, whose 1990 album To the East, Blackwards is a politically conscious, Afrocentric classic of that era. Today, Paradise is the grandfather of the museum, which hoards more than 30,000 objects in a provisional location across the street from where the final one is being built, with an opening scheduled for the end of 2024. “Five blocks from Yankee stadium,” he winks. It will overlook the Harlem River, in an area that has been experiencing some urban renewal, thanks in part to the museum’s construction. It’s no coincidence that the building in which it is being built will also offer 500 affordable housing units to the Bronx population, which is always lagging behind the city’s quality-of-life indicators. The museum, meanwhile, will occupy two floors and will have a restaurant and stages that can be rented for performances. “There’s no market-rate housing in the building: the apartments are for people struggling to make ends meet. The project represents the spirit of the community where it was born,” the director emphasizes.

The beginnings

The recipe for hip hop’s success is attributed to DJ Kool Herc. He spun the same record on two turntables, alternating between them to isolate and prolong the percussive breaks — the most danceable sections of a song. It was a technique that filled the floor with dancers who had spent many hours polishing their moves. Competition — the desire to survive in a hostile environment — was a driving motivation for the original hip hop dancers. DJ Kool Herc’s invention was a shock that still electrifies the streets.

According to most theorists who study the genre, six basic elements come together in hip hop culture: the DJ (with his manipulation of rhythms and music); the rapping of the MC, or master of ceremonies (poetry recited to the rhythm of a measure); the breakdancing, or acrobatic and spasmodic dance; the graffiti; the ability to permeate other disciplines (literature, cinema), as well as the awareness — or empowerment — of hip hop identity. There’s pride and activism. No one, Paradise Gray chuckles, has ever dedicated themselves to a single element. “In this community, we do it all.”

The role of DJs is paramount. From James Brown to The Meters, they “cooked” the classics by incorporating ingredients, that is, innovations, on an infinite scale. “This forever changed the way we think about turntables,” Gray adds. The echoes of that impromptu party in the Bronx spread through urban and suburban communities.

Celebration in New York

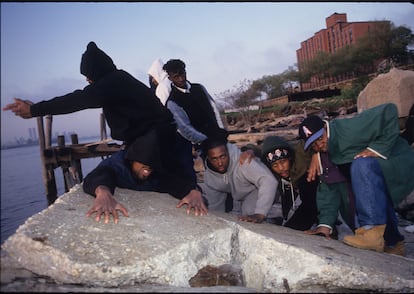

This month, there’s a big party in New York, thanks to the museum and the mayor’s office, which has made a strong commitment to the celebration. The urban geography is going to get drunk on music. For the 50th anniversary of hip hop, you can see the names of luminaries from the movement splashed on taxis, kiosks, buses and murals. Among dozens of concerts, the Wu Tang Clan hosted a free marathon this past Thursday in Queens.

Political correctness — once so alien to the movement — has also arrived. During the day, those over the age of 13 can attend the performance. But, during the night sessions, you will need to be over 21.

Today, DJs spin the turntables in São Paulo. MCs rap in Arabic in clubs in Qatar. B-boys and B-girls do baby freezes in Finland, while breakdancing has made it into the theaters. Respectful graffiti is on a part of the Great Wall of China; young poets rap lyrics in Washington, D.C. The jargon is universal — as universal as the colors of the people who deploy it.

Richard Colón was just 10-years-old when his cousin took him to his first schoolyard party in 1976. “I freaked out,” he told Jeff Chang, author of a hip hop history titled Can’t Stop Won’t Stop. “I just saw all these kids having fun… I immediately became a part of it.” Today, Colón — a Bronx-born Latino — is better known as Crazy Legs. He’s credited with having exported breakdancing to London and Paris in the 1980s. A b-boy — accompanied by his group, Rock Steady Crew — he hardened himself on the asphalt, receiving scars in his quest to conquer the street. The Latino b-boy became a trendsetter, and he’s still around, nearing the age of 60, a symbol of the important Latin dimension to hip hop.

In terms of individual inspiration, no one can beat soul singer James Brown. All those who would go on to become figures in the movement clung to his music. His energetic dance moves have inspired b-boys and b-girls around the world, while his song Get on the Good Foot was one of the first breakdancing anthems. Over the years, breakdancing greats such as Colón’s Rock Steady Crew, the Mighty Zulu Kingz, the Lockers, the Electric Boogaloos and many more have revamped Brown’s style with original twists. Competition and innovation are the engines of hip hop.

Social peace (if it ever really existed) in New York City owes a lot to hip hop. In decades as violent as the 1980s and 90s, DJs guided and channeled the energy of young people living in an adverse context. “Music arose from the economic and sociopolitical pressure that the Bronx was experiencing. We were surrounded by gangs, murderers, pimps, hustlers, drug dealers… and yet, the kids in this community were able to create a multi-billion dollar industry,” Gray recalls. With holes in the soles of their shoes, ripped pants and do-it-yourself haircuts, they were strong and proud. The genre also had very clear dimensions that were oftentimes political. For instance, Afrika Bambaataa includes fragments of speeches by Malcolm X and Martin Luther King in his compositions.

Today, rappers and MCs such as Jay-Z, MC Lyte and Kendrick Lamar hold high profiles in the hip hop universe. But, in the beginning, the owners of the microphone used it to make announcements, such as the date of the next party, “or if someone’s mother came to the party to look for [their son], to notify him through the microphone,” recalls Grandmaster Caz in Yes Yes Y‘all, an oral history about the beginnings of hip hop. Rappers became cultural protagonists over time. The belongings of Tupac Shakur — one of the most influential artists in modern history — monopolized the Sotheby’s auction house on the occasion of the genre’s 50th anniversary. There were award-winning records, as well as his royal ring — made of gold, rubies and diamonds — which the musician wore in his last public appearance, shortly before he was assassinated, in 1996. This past July, it sold for a million dollars — five times the starting price.

Spoken word

The notion that hip hop is also a fluid form of poetry is accepted without question by academics. Before hip hop and rap took hold in the U.S., spoken word poetry occasionally made its way into jazz shows. Many experts associate this form of art with The Last Poets — a group from Harlem — and The Watts Prophets, from Los Angeles. Both emerged in the late-1960s and combined political poetry with jazz improvisation. Graffiti is also an element that predates the music and dance scene itself: tagging, as its artists call it. In 1967, a Philadelphia teenager named Darryl McCray spray-painted his alias — “Cornbread” — on walls and trains. In 1968, the trend jumped to New York. And, by the mid-1970s — following hip hop — it became the city’s second skin.

The special interest that the New York City Council has taken in the initiative to build a hip hop museum has a straightforward explanation: hip hop — as a tourist attraction — is capable of regenerating the district that gets the worst press in the city. “People from all over the world come to our temporary museum. From Japan, France, Spain, Africa, from all over Europe, Amsterdam, England, Germany. And it’s very exciting, because most of them have never been to the Bronx,” Bucano smiles. “The [finished] museum is going to be a major economic catalyst for this part of the South Bronx, because it’s going to bring tourists from all over the world.” Since the museum’s inception, Microsoft has been the main sponsor.

The rest of the city is also showing off, with hip hop-themed routes throughout the Big Apple, exceeding the limits of the Bronx. “In the 1980s, hip hop came to the center of Manhattan. Sugar Hill and all the artists of the time ended up performing at the Roxy, where Basquiat and all those people from the downtown art scene went — the place where art and music collided,” Ralph McDaniels tells EL PAÍS in a video call. Known as “Uncle Ralph,” he’s the producer of music videos by artists such as Nas. In 1983, he created Video Music Box, which, at the time, was a pioneering music video program. This was two years after MTV began — Uncle Ralph explains that it was barely seen, “because very few people had cable… that’s why artists came to our studio.” Alongside Paradise Gray’s Latin Quarter, the Roxy was the club of all clubs.

Looking to the future

Touched by the magic wand of brands, does hip hop have a future? Or could it die of success? “Hip hop was founded on peace, love, unity and fun. And now, it has morphed into everything, from music to fashion to sports. The 2024 Paris Olympic Games will have breakdancing [competitions] — it’s the first time that this has happened,” explains Bucano. “So, it’s transcendent and it will continue to grow. And, as the official trustees of hip hop, our job is to make sure that hip hop is celebrated not only as we know it in the U.S., but all over the world, because each country has embraced its culture to make it their own.”

The commemoration is also seen as a return of the wealth generated from hip hop, “for our own repair,” Bucano emphasizes. This is an attempt to put a multi-billion dollar industry back where it was born, because the South Bronx has traditionally been a place neglected by New York City itself. “We continue to be the voice of the voiceless, the voice of the poor around the world. For freedom, justice and equality, hip hop continues to be the best movement for the youth of the world,” concludes Paradise Gray.

Before ending the interview, he firmly shakes hands, giving the sign of peace and love, with a string of thanks. “Thanks to DJ Kool Herc, Cindy Campbell, Grand Wizard Theodore, the L-Brothers, Cold Crush, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, the Funky Four Plus One, the Fantastic Romantic Five, DJ Charlie Chase and Tony Tone, DJ Breakout and DJ Baron Lopez and thousands of other superheroes who gave their blood, sweat and tears so that we can be here today, celebrating.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.