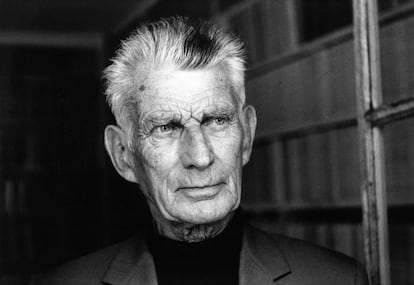

Welcome back, Samuel Beckett

The Irish Nobel Prize winner was a precise portraitist of terrifying years that could return at any moment

The 20th century brought us Stalin, Mao, two world wars, the Holocaust, atomic bombs and a couple more carnages that I would rather not recall. Several million people died as a result, according to the most conservative calculations. Logically, the soul of Europeans was shaken, and it is admirable that we have survived as a species. A Martian would have expected us to commit suicide once and for all with a big nuclear bash.

The battered world conscience led to several new outcomes in terms of human representation. Living with the constant threat of extinction affected artists, who are the ones that truly represent us and not politicians. So the artists began to represent us as they saw us: strange, deformed, shapeless, anomalous, invisible, crippled, stuttering, or simply mute.

We have been more temperate for several years now, and it seems that we are now able to analyze that past, which was called “the avant-garde,” with some calm. Not everywhere, of course, but it is possible in a West that is fading, but which is no longer massacring its slaves. And the effect that this awareness of destruction had on literature was the emergence of a group of immense writers who could no longer represent humans in a luminous and heroic way, so to speak. However, it would be a very bad idea to leave them for dead. Joyce, Proust, Kafka, Faulkner, Bernhard, Manganelli, Benet, Rulfo — throughout the West, a literature took shape during the 20th century in which only the bare form remained with a capacity to simply be. And one of its main writers was Samuel Beckett.

It is a source of joy that this difficult, harsh, dark, but wise literature’s ability to fascinate, moralize and illuminate us has not run dry. And reading these artists is a very convenient way to understand that everything could go dark at any moment. I am currently celebrating the release of a new Spanish translation of Watt, Beckett’s last novel in English, by an affordable publishing house that can reach many students (Cátedra).

The story behind this novel is another novel in itself, well told by the translator José Francisco Fernández in his extensive foreword to the new Spanish version. Beckett wrote it while fleeing from one hideout to another as a member of the Resistance, pursued by the Nazis who were occupying France. In those absurd conditions, Beckett carried his notebooks, in which he was writing and annotating what would finally become the novel Watt, which is the name of the main character, who is as non-existent as Godot, the most famous of Beckett’s characters. Watt has a partner, Mr. Knott, whom he serves in a parody of the old novels of masters and servants that have been immortalized thanks to television series like Upstairs, Downstairs.

Rejected by the publishing world

Although he finished it in 1945, Watt was not published until 1953 after being rejected by almost all English and American publishers, who were very reluctant to recognize that this convulsive and sarcastic prose was a faithful portrait of 20th-century civilization. And once it was published it barely made an impact. It was not until 1968 (what a year!), when it was published in French by the Minuit publishing house, in the author’s version and with the help of the Janvier couple, that enthusiasm for the novel would begin to get some traction. The French powers-that-be recognized themselves in the portrait of the warped, disintegrated human race, described with a lacerating irony that the Irishman created out of nothing.

There were other effects that fascinated those who dominated literary opinion at the time. One of them was the obvious caricature of Descartes, a philosopher whom Beckett always counted among his favorites, and the reference to whom was immediately picked up by the masters of structuralism and deconstruction.

Welcome back, then, to our Beckett, a precise portraitist of terrifying years that could return at any moment.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.