Manhattan District Attorney sets precedent with return of Nazi looted art

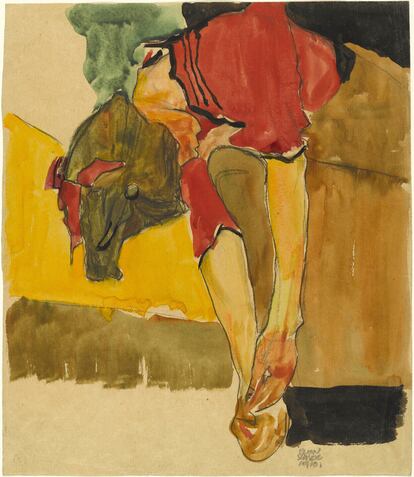

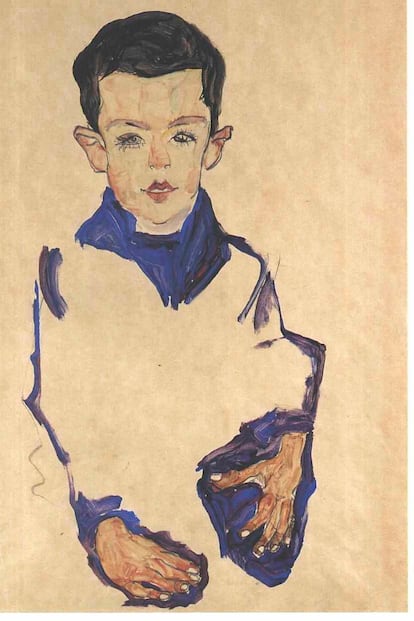

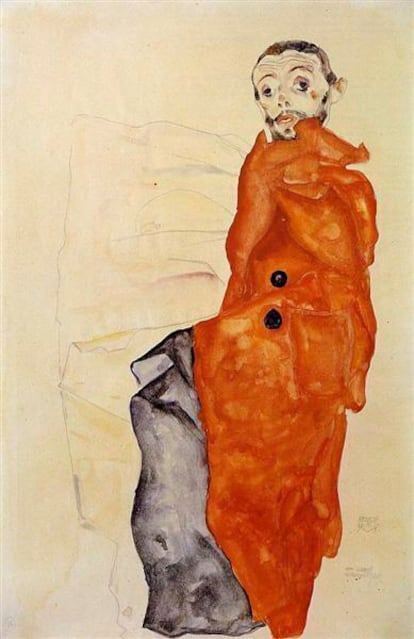

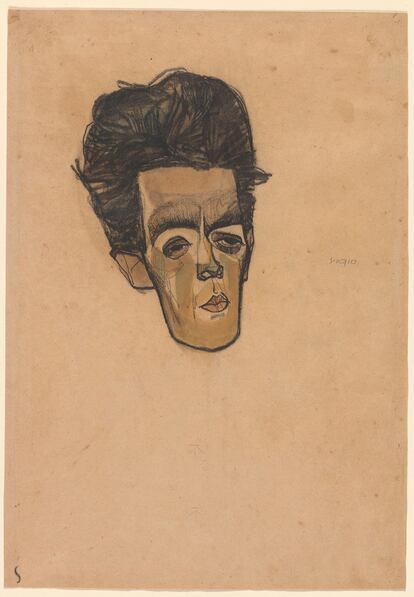

Five major U.S. cultural institutions have surrendered seven Egon Schiele drawings that were stolen from a Holocaust victim

There is a straight, if broken, line leading from the Monuments Men, the Allied group of experts that fought Nazi art looting during World War II, and the Manhattan D.A. Office’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit, whose investigators have scored a goal: the return of seven artworks to the family of Fritz Grünbaum, an Austrian-Jewish cabaret performer whose art collection was stolen by the Nazi regime. Despite the suspense-tinged, epic nature of their task, the Monuments Men, whose exploits George Clooney brought to the big screen in 2014, were unable to locate these drawings, and it has taken several decades to close the chapter. The happy ending, in the opinion of the expert Leila Aminoddaleh, is especially gratifying “because the result of the litigation is both legally and morally fair.”

The case has put the spotlight on the institutions that had been treasuring the drawings: the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the Ronald Lauder Collection, the Morgan Library, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art and the Vally Sabarsky Trust in Manhattan (the MoMA and the Trust had two works each). All five institutions, which are not the first and probably not the last to find themselves in this situation, voluntarily surrendered the works after they were presented with evidence that they were stolen by the Nazis from Fritz Grünbaum, a cabaret artist who was fiercely critical of the Nazis in his shows and off stage. In the period between wars, cabaret was something of a cultural genre unto itself in Central Europe, and a hotbed of artistic activity that included Jewish creators.

The sum of all the synonyms of the concept of plunder is insufficient to encompass the breadth of Nazi looting, which wiped out private collections and entire museum funds, part of which were put up for sale to finance Hitler’s government. The individual in charge of this was Karl Haberstock, a dealer with few scruples who became the dealer of the Third Reich and who decided the fate of some 16,000 pieces of “degenerate art,” as Egon Schiele’s work was described. The latter’s art was removed from German museums between 1933 and 1938 and confiscated in the annexed territories of Austria and Poland, in addition to assets belonging to academic and religious institutions and companies that were Aryanized.

The importance of this return underscores two things: that no institution is free from housing funds of dubious origin, and that the debate on cultural property — the scrutiny of pieces of uncertain origins, acquired irregularly, as well as their incipient restitution to their countries of origin — is even more poignant in the case of Nazi looting because there are still living heirs, such as Grünbaum’s, whose efforts to recover the works of their ancestor lasted almost eight decades.

“The fact that it took decades for the family to recover what is rightfully theirs is, frankly, inconceivable. The decision by museums and collectors to return the works, after dragging their feet for years, restores history and opens the door to other acts of restitution. Unfortunately, the threat of criminal charges from the prosecution has been necessary for them to act,” says Sarah Lichtman, chair of Pratt Institute’s History of Art and Design program, that has investigated this period in depth. For this reason, Lichtman emphasizes, “the importance of returning Schiele’s works cannot be stressed enough. The Nazis stole Fritz Grünbaum’s collection and sent him to Dachau, where he was murdered.”

For art and cultural heritage law attorney Leila Amineddoleh, who has closely followed the process, “the restitution is very significant because it indicates the willingness of American courts to examine decades-old transactions and, to a certain extent, repair the errors of a historical atrocity.” According to Amineddoleh, it is a reminder “for collectors, dealers and museums to properly examine the works in their collections and ask difficult questions about the art that changed hands during World War II.”

No institution is free from the shadow of suspicion, which is why the dozen cultural entities consulted for this story declined to comment. “We do not comment on the activities of other museums or the actions of the New York district attorney,” was the reply from Smithsonian Provenance, a department of the Smithsonian Institution that is dedicated to tracking the artistic looting of that era.

“The seizure and return of the works is the result of a dispute between Grünbaum’s heirs and the art dealer Richard Nagy,” Amineddoleh recalls. Nagy was forced in 2018 to return two of the drawings in dispute, the lawyer recalls. The case, therefore, “reveals the will of law enforcement to investigate the origin of a work — its ownership history — and enforce property rights dating back more than eight decades.” In addition, the action of the Manhattan D.A.’s office “provides additional legal precedent and support to other heirs to claim works that were stolen from relatives or sold under duress.”

According to evidence gathered by the prosecution, Grünbaum owned a significant art collection, including more than 80 drawings by Schiele. Arrested by the Nazis in 1938 after the annexation of Austria, at Dachau Grünbaum was forced to sign a power of attorney in favor of his wife, who later had to hand over the funds to Nazi officials. The collection was inventoried and confiscated in a Reich-controlled warehouse in September 1938. Its whereabouts remained unknown until some works reappeared at a Swiss auction house in the 1950s.

In line with the rest of the allies, who after World War II worked hard to return objects to their countries of origin and their true owners, in 1947 the North American State Department sounded the alarm about the influx of Nazi looted art and asked galleries and museums in the United States to be especially vigilant about any work coming from Austria, among other European countries. Despite the warning, thousands of pieces of dubious origin entered the country and ended up hanging in the best museums in good faith, without knowledge of their legal ownership in most cases.

Joint guidelines for US museums

It was not until 1998 that the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) and the American Alliance of Museums (AAM, formerly the American Association of Museums) systematized their efforts with the publication of guidelines for the management of objects that could have been stolen by the Nazis. The AAMD and AAM, in an agreement reached with the Presidential Advisory Commission on Holocaust Assets in October 2000, further recommended that museums put all available information about certain objects online so that the public could contribute. Under these guidelines, museums must identify objects in their collections created before 1946 and acquired by the museum after 1932, that underwent a change of ownership during the Nazi era (1933-1945) and that were or can be thought reasonably to have been in continental Europe between those dates.

This is what, for example, the Meadows Museum in Dallas did with two artworks by the 17th-century Spanish painter Murillo. Amanda Dotseth, director of the museum, recently explained to this newspaper the scrutiny to which the paintings were subjected. “Algur H. Meadows bought two paintings by Murillo, Santa Justa and Santa Rufina, in the 1960s, but we discovered that they had been seized by the Nazis from the Rothschild family in France. We investigated until we found evidence that these two works had been returned to their owners before we acquired them and they were incorporated into the Meadows.” The museum continues to deepen the scrutiny through so-called due diligence, “the investigation of the provenance of acquisitions. You always have to continue investigating the history of the origins of a work, as well as its modern history.”

Under the current district attorney, Alvin Bragg, the Antiquities Trafficking Unit at the Manhattan D.A.’s Office has recovered almost 850 items stolen in 27 countries and valued at more than $165 million, according to July data. Bragg took office in January 2022, which underscores the intense pace of investigation. In total, the ATU has recovered more than 4,500 antiquities stolen in 30 countries and valued at almost $390 million, according to data from the D.A.’s Office.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.