Robert Oppenheimer: The story of the father of the atomic bomb

Director Christopher Nolan’s film about the physicist will hit theaters in June. The movie is based on ‘American Prometheus,’ a masterful biography that draws on 30 years of research about the rise and fall of the scientist who lent his talents to create the ultimate weapon

There are several contenders for the uncomfortable title of father of the atomic bomb. It can be ascribed to Albert Einstein, who wrote the most famous equation in history, E=mc2, in 1905, showing the world that a small amount of matter (m) could be transformed into an enormous amount of energy (E) when multiplied by the square of the speed of light (c2), a gigantic number. Or it might be attributed to Leo Szilard, the eccentric Hungarian physicist who visited Einstein on Long Island in 1939 and convinced him that the Nazis could get their hands on the Belgian Congo’s abundant uranium reserves. Or perhaps credit should go to Alexander Sachs, the Lehman Brothers economist who immediately understood that, if it was possible to design a weapon with the destructive power predicted by those physicists, the United States should build it. And, of course, there’s president Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who took all of the above seriously and financed the Manhattan Project to create the deadly device.

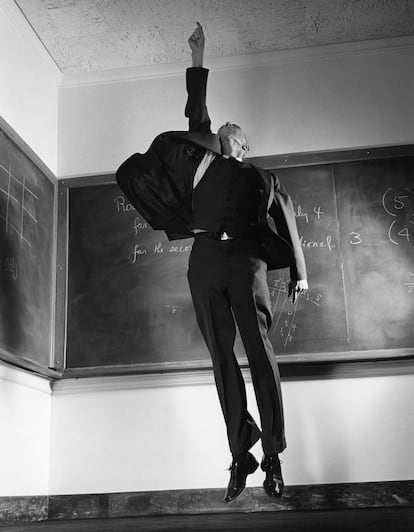

But they all pale in comparison to Robert Oppenheimer, the Manhattan Project’s chief scientist, its demiurge and inspiration. He attracted the best physicists of the time and put that talent to use for the most frightening military purposes, the ultimate weapon, which would change 20th century history. Director Christopher Nolan is bringing the renowned scientist’s story to the silver screen in June of this year. The film, called Oppenheimer, is based on Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin’s landmark biography, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer.

American Prometheus is a monumental work. Both columnist Bird and historian Sherwin are specialists in the development of nuclear weaponry and spent 30years researching every source — on paper and in the flesh — related to Oppenheimer. The biography was published in 2005 and won the Pulitzer Prize the following year. Sherwin died in 2021. The tome not only tells the story of the lead scientist in a remote, top-secret laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, but also that of the young son of Jewish immigrants in early-20th-century New York, his rise as an American hero and his descent into the hell of McCarthyism.

The nickname Prometheus suits Oppenheimer well, not only because that titan of Greek mythology stole fire from the gods and gave it to men (the most obvious part of the nuclear analogy), but also because Zeus threw such a tantrum over that act of betrayal that he had Prometheus nailed to Mount Caucasus to have his liver cruelly and repeatedly eaten by an eagle. Despite the fact that the bomb created under Oppenheimer’s stewardship at Los Alamos resolved World War II in his country’s favor and satisfied most of Washington’s hawks, the Republican Party began to distrust the physicist in the 1950s and ended up destroying his life and reputation during the Cold War.

As a young man, Oppenheimer had lived through the Great Depression of 1929 and the rise of fascism in Europe (he studied quantum physics in Germany in the 1920s). In New York, he was involved in social movements in which communists and other left-wing sympathizers fought against racial discrimination and economic inequality. Later, after the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Oppenheimer — like many other scientists with whom he worked at Los Alamos —became an activist against nuclear proliferation. When Republicans came to power in 1953, the military figures and strategists who had advocated the mass use of atomic bombs gained power in the White House. Soon, they set their sights on Oppenheimer, the war’s scientific hero and the voice who stubbornly spoke out against their strategy. That was the end of his public reputation and intellectual influence. Zeus is unforgiving.

The authors of American Prometheus quote New York novelist E. L. Doctorow, who wrote in 1986: “We have had the bomb on our minds since 1945. It was first our weaponry and then our diplomacy, and now it’s our economy. How can we suppose that something so monstrously powerful would not, after 40 years, compose our identity? The great golem we have made against our enemies is our culture, our bomb culture — its logic, its faith, its vision.” That vision has not gone away in our own day, and perhaps it never will.

In order to write this book, the authors compiled thousands of documents from archives halfway around the world, studied all of Oppenheimer’s writings and talked to his relatives, colleagues, friends, military chiefs and political contacts. They also reviewed the thousands of pages the FBI collected on him for over a quarter-century of persistent but not always justifiable surveillance. Bird and Sherwin’s biography offers a powerful glimpse into that inconceivable abyss; in June, it will also provide the basis for Nolan to bring Oppenheimer’s story to life on the big screen.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.