The umpteenth resurrection of Godzilla, the radioactive monster of Japanese origin

With ‘Godzilla Minus One,’ the famous saga has reached its 37th film. Whether in Japan or the United States, the legend of the reptilian creature functions both as mass entertainment and as a portrait of society

In the same year that Oppenheimer achieved notable box office success and renewed public interest in the story of the atomic bomb, Godzilla roared again from Japan. While the Christopher Nolan film still doesn’t have a release date in Japan — given the controversial fact that the film only offers the perspective of the aggressor in the 1945 American nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which killed more than 220,000 people — Toho Studios has brought back its emblematic figure. The reptilian creature gave face and form to national trauma in Japan after the end of World War II, when the first film in the series was released in 1954. Set just a couple of years after the nuclear attacks, Godzilla Minus One — the 37th film in the saga — has already become a massive box office success in Japan. It is scheduled for release in North America and Europe on December 1, 2023.

The film — which isn’t related to the ongoing American Godzilla franchise (the next sequel, Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire will be released in 2024) — is directed by Takashi Yamazaki, a renowned filmmaker who has previously gained international attention for his live-action adaptations of manga. In a recent interview with Deadline, he offered some insight into his vision of the creature, while making comparisons between the Japanese and North American models: “Toho’s Godzilla is pictured as both a monster and a god, while American-produced Godzilla seems to have a more monstrous flavor.”

The filmmaker also clearly stated his intention to inject Godzilla Minus One with the allegorical and political factors that have characterized the best adventures of the gigantic lizard. “I am hoping that people will feel the reality of a government that doesn’t do much in the face of national emergencies and that things do not go very well without civil initiative to resolve them. Also, the results of cronyism and disregard for life.”

“While Godzilla has been a multifaceted creature that has served as a powerful metaphor for a variety of themes over the years — such as nature’s revenge against humanity, environmentalism, human arrogance, or the national spirit of Japan and its military power — I think its most iconic representation is related to the nuclear threat,” opines film critic Juan Luis Sánchez, in an interview with EL PAÍS. “Godzilla’s skin — composed of a layer of overlapping scars — resembles the anomalous tissue growths that develop after [exposure to] nuclear radiation.”

Sánchez — who claims to have “high hopes” for the new film — doesn’t hide his disappointment with the American versions of the creature. In Roland Emmerich’s adaptation, Godzilla (1998) — set in New York — the origin of the monster was separated from the atomic bombs dropped by the United States and blamed, instead, on the French nuclear tests. The stalwarts were also not pleased that the beast’s radioactive breath was suppressed. More of a lighthearted blockbuster in the spirit of Jurassic Park (1993) than the original, the film was poorly-received.

“[The idea] that [Godzilla] is a mutated iguana that seeks to reproduce is a bit ridiculous… as are the cheesy dialogues,” the critic scoffs. He also doesn’t find subsequent attempts by Warner Bros. and Legendary Pictures to be much better. He describes a “bittersweet” taste left by Gareth Edwards’ Godzilla (2014), as it contained a “simplistic environmental message” and a monster who wasn’t very fierce. “He’s even careful when he walks between buildings, so that he doesn’t break anything. I went to see Godzilla, and I met Lassie!”

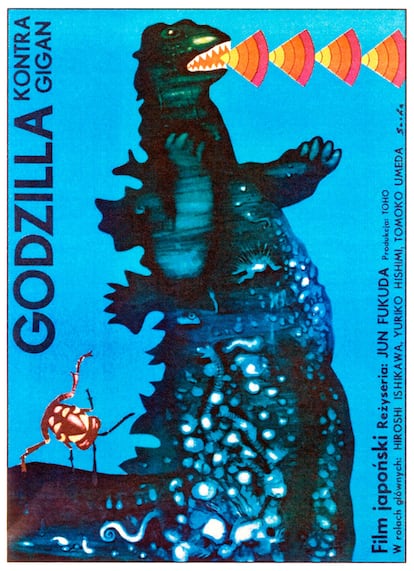

Faced with “supposedly overwhelming special effects,” the critic acknowledges his longing for the Godzilla that used to be played by a stuntman in a suit, jumping on models of cities. He also prefers “the charm” of the Japanese King Kong against Japanese Godzilla (1963) compared to the contemporary Godzilla vs. Kong (2021). However, don’t get your hopes up for a retro twist in Toho Studios’ new film: Godzilla Minus One has also been created by digital means.

Since the creature’s first appearance in the 1954 film by Ishirô Honda (the director of eight Godzilla titles and pioneer of kaiju-eiga, the Japanese genre of enormous monster films), Godzilla has appeared a total of 37 times on the big screen. Godzilla is about to reach its 70th anniversary in excellent shape, with a cultural relevance beyond any doubt, productions on two continents, undeniable success at the box office and new interpretations that are contributing to enriching the myth. Far from the times when low-grade sequels were constantly being churned out, Toho’s previous effort — Shin Godzilla (2016) — was already hailed as one of the best films of the year. It generated great interest for the way in which it channelled the horror of the Fukushima nuclear disaster and the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, as the original film dealt with the results of the atomic bombs.

Made by Hideaki Anno — creator of the Neon Genesis Evangelion animated series — Shin Godzilla also functioned as a critique of the management of the recent catastrophes and the ineffectiveness of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces (following its defeat in World War II, Japan’s constitution prohibits it from having armed forces with the potential to wage war), as well as a reminder of the continued validity of the atomic danger. It also salvaged the monster’s terrifying aura.

Godzilla Minus One isn’t linked to said installment or any other, as it’s more of an origin story. Continuity — it must be said — has never been a great concern for the creators of the saga. Even when Godzilla dies, Toho Studios has never hesitated to bring him back.

The creature has been a hero or a threat, depending on which movie you watch. Becoming a Japanese icon almost immediately after its 1954 debut, the public’s love for the character led Toho Studios to turn it into the country’s kind defender for several films. Godzilla has been a protector against other adversaries, such as the three-headed dragon Ghidorah, the great lobster Ebirah, or the robot Mechagodzilla. From the suspense and anguish of the first installment, Godzilla jumped to the children’s genre, in films such as Son of Godzilla (1967), in which the super lizard teaches its offspring to shoot lightning from his mouth and defend himself against family-sized insects. And, a couple of years before that, in Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965), aliens ask humans to give them Godzilla in exchange for a cure for cancer… in what actually turns out to be an evil plan to control the creature’s mind and conquer the planet.

Godzilla’s potential as a symbol upon which to project ideals or political manifestations was not ignored even by Kim Jong-il — the late supreme leader of North Korea — who had his own monster counterpart produced. This glorious and metallic hero of the proletariat appeared in Pulgasari (1985), a cult title in film circles. Even fan-made montages — such as the stop-motion short film Coming Out (2020), where Godzilla recognizes the identity of his transgender daughter — demonstrate that the radioactive animal can even join the LGBTQ cause. True to his nature, Godzilla never stops transforming.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.