Why is the first Mexican flag stored inside a frozen Norwegian mountain?

An icy mine near the North Pole holds valuable treasures of human history – Vatican manuscripts, Latin American history, Brazilian art and even a Colombian podcast

What if, faced with looming threats of major wars and cataclysmic natural disasters, we had to find a way to save memories and somehow preserve the record of humanity? If we couldn’t store those memories digitally because they’re too big, too expensive, too everything – what would we do? These questions are far from hypothetical and not at all improbable. People have been thinking about them for years, and governments like Mexico, India and Norway have been taking action.

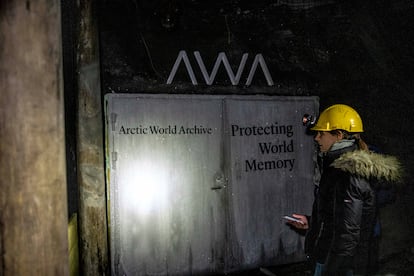

In the Arctic Ocean, halfway between Norway and the North Pole, lies a mountain in the Svalbard archipelago. Within this mountain, 300 meters below the surface, there is an old mine. The air inside is cold and dry, and there is no natural light. Many people think it’s the safest place on Earth. Since 2017, the original Mexican flag, along with the country’s declaration of independence and every constitution from 1814 to 1917 have been stored here. There are also several manuscripts from the Spanish conquest and 492 historical files from the Mexican judiciary, all in digital format.

“It’s not the first time that our national archives have been kept in an underground cave,” said Gustavo Villanueva Bazán, a Mexican historian and expert in records management at the University of Andalusia (Spain). “During the French intervention, Benito Juárez moved around the country, taking the national archives with him. From September 1864 to May 1867, he sought refuge in a cave known as Del Tabaco, located in the municipality of Matamoros de La Laguna, Coahuila. After the Mexican Republic was reestablished, the documents were recovered from the cave.”

But the reasons for storing the Mexican manuscripts and artifacts in the Arctic World Archive are different now. It aims to ensure long-term preservation and security of the digital archives, free from unauthorized access and hacking, for thousands of years. Additionally, this location minimizes the carbon footprint associated with traditional storage methods. “Preserving archives is crucial for avoiding past mistakes and establishing a social and national identity. Our collective history shapes who we are as a society. The documents in this archive reflect the daily administration, legislation, activity and relationships of our society,” said Villanueva.

Brazilian artwork and a Colombian podcast

In addition to the Mexican archive, there are several notable artworks and artifacts preserved by renowned institutions. These include The Scream by Edvard Munch, safeguarded by the National Museum of Norway; artwork by Rembrandt; manuscripts from the Vatican Library; and an ultra-high resolution 3D scan of the Taj Mahal in India. From Latin America, there are works by Brazilian artists André Terayama, Almicar de Castro, Antonio Bandeira, Orlando Teruz, Laura Lima Nômades and Heitor dos Prazeres. There’s also a collection of over 20 episodes of the Mizter Rad Show podcast. Hosted by Colombian Mizter Rad, it features interviews with influential individuals who are shaping the future of humanity.

“I was listening to Vitalik Buterin, the founder of Ethereum, the other day. He was talking about the Arctic World Archive – a bunker in northern Norway where they store all of humanity’s most precious digital archives. I got so intrigued that I did some research and reached out to the founders, Katrine Loen and Rune Bjerkestrand,” said content creator Mizter Rad. “After interviewing them, I realized that this archive is not just for big national institutions. It’s actually open to anyone who meets certain legal requirements. Now, it’s not cheap or easy to access. But it’s a chance for anyone to become a part of history that’ll be preserved for the next 2,000 years. Folks like you and me can have our stories told too.” The Colombian podcaster deposited his audio files in the very heart of the permafrost and paid $160 per gigabyte, plus the costs of the trip to Norway and the delivery ceremony.

Mitzer Rad explains how this global archive operates in a podcast episode. Coming from the film industry, the founders realized that 35mm films had been highly effective means of documenting life for decades. “We realized these photosensitive films are amazing at transmitting information, so we thought, hey, maybe we can handle data too. So we turned the film tech into a digital data transporter, encoding it in bits and bytes as a super high-resolution QR code,” said Rune Bjerkestrand in the podcast.

All the files, including the Mexican flag and the façade of the Taj Mahal, are stored digitally. They can be easily decoded in the future, even if the technology of today (like QR codes) is long forgotten. “You don’t need to know a thing about our time to understand these files. All you need is light, something that can capture it, like a camera, and a computer or platform that speaks the language of zeros and ones,” said Bjerkestrand.

The combination of secure, durable storage technology that is resistant to hacking, easy to access, and stored in a remote place has attracted numerous institutions that are preserving the treasures of human memory there. However, Villanueva reminds us that digital files always entail some loss. “In that distant future, people won’t have all the context.” They won’t know whether the documents were made of parchment or white paper, or what it felt like to touch the paper. They won’t know if the painting was done on cloth or canvas, or that the walls of the Taj Mahal were made of red sandstone. “There’s no way to preserve that kind of information for hundreds of years.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.