Author Eve Fairbanks: ‘Many Black South Africans long for an apology’

In ‘The Inheritors,’ the American writer explores the country’s post-apartheid contradictions through the lives of three people

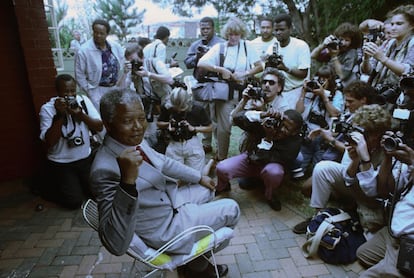

Apartheid is the Afrikaans word for “separateness.” The term referred to the system of rigid racial segregation and significant inequality between the white minority (the Afrikaners) and the Black majority imposed in South Africa by the National Party when it came to power in 1948. The era came to an end in the early 1990s, when a heroic and smiling Nelson Mandela was released following 27 years in prison. He went on to win the presidency, seeking reconciliation rather than revenge.

Apartheid ended, and the country became a more just and livable place, especially for the majority Black population. But you don’t go from hell to heaven in one giant leap. The hangover from decades of social injustice lingers, and many loose ends were left untied. American political writer Eve Fairbanks examines post-apartheid South Africa through the lives of three individuals: Dipuo, a female activist who worked to overthrow oppression; Malaika, Dipuo’s daughter who drifts through a violent world; and Christo, one of the few remaining white South Africans tasked with preserving the status quo ante.

Dipuo and Christo were both born around 1970 and became adults when South Africa was changing dramatically. “They entered a disconcerting world,” said Fairbanks. Malaika was born in 1992 — in a “free” country — and grew up with certain expectations. However, she soon realized that her future was not as perfect as she had hoped, as previous generations still influenced much of life in South Africa. “She was told that she lived in an amazing new world, but soon found out that it was still deviously shaped by old villains and memories,” said Fairbanks. In The Inheritors: An Intimate Portrait of South Africa’s Racial Reckoning (2022), Fairbanks tells real stories — human and complex — another version of the history taught in South African schools.

Fairbanks’ interest in racial issues began at an early age. Raised in a right-wing family in the southern United States, she questioned why the politicians her parents supported opposed racial justice. This curiosity led her to seek a deeper understanding by studying similar conflicts in different settings. In 2009, she relocated from Washington to South Africa — the epitome of racial conflict — where she lived for 14 years.

“I remember feeling like the entire world was there in that country,” Fairbanks recalls. “It seemed like South Africans were grappling with the same things that people all over the world were trying to understand.” For instance, the issues of societies that fail to adapt their traditions and ethics to the realities of a diverse citizenry. The challenges of treating people differently based on class, gender, and race. And climate change, language diversity, infrastructure, the concept of happiness, family, work, and migration. “South Africa is a country where you’ll find the descendants of white settlers and the Blacks who were colonized. So, you have people trying to remember ancestors who did bad things, and others struggling with how to remember their people’s suffering,” said Fairbanks.

Two different countries merged into one

When a society is forced to reset and rebuild from scratch, problems are bound to arise. “During apartheid, white South Africans kept Blacks out of leadership and public society so much that when apartheid ended, it was like two different countries, two worlds that suddenly had to come together as one,” said Fairbanks. Most people view the end of apartheid as a significant achievement, but it’s not that simple. Fairbanks observes that American society actually views the end of apartheid as a failure.

“I think foreigners see in South African history what they want or hope to see.” Some mistakenly believe that moving on from a history of colonization is easy, assuming that the defeated won’t fight back and victims won’t seek revenge. They think everything can be fixed. Others believe that racial justice actually threatens the system, as long-standing inequalities support a solid social structure. Both perspectives, though contradictory, are based on disconnected fragments of South African history. Fairbanks found two main causes for the country’s current issues. First, South Africa’s economy and institutions were originally designed for a different population than the one that exists today. Second, the country’s citizens perceive their homeland differently based on past experiences and memories.

Some white South Africans avoid guilt so it doesn’t overwhelm them. Fairbanks noticed that some even become ostentatiously unapologetic. However, some Blacks continued to believe that whites were superior, as it gave meaning to their own oppression. They wondered why they hadn’t freed themselves sooner. There was a noticeable phenomenon that was both human and disheartening: Black South Africans who achieved upward mobility started adopting classist attitudes toward their less fortunate peers. Fairbanks even observed an uptick in racist attitudes among whites. “Many South Africans think that white youths tend to be more racist than their parents and feel anxious about the rise of white supremacy,” she said. If racism gains momentum in the absence of apartheid, it might bring relief to older South Africans. After all, it was only natural, they might argue.

Racism was actively promoted by the segregation system, convincing whites that they lived in an ideal world surrounded by a bubble of like-minded peers. “The white government of South Africa from 1961 to 1994 literally shaped the physical landscape, digging valleys and strategically locating factories... to prevent whites from seeing Blacks,” said Fairbanks, who knows many white South Africans who, in their youth, believed their country was predominantly white. “White South Africans truly believed they had the best army, the tastiest fruit and wine, and the best universities in the world. The government did a very good job of concealing the complicated and broader truth.”

Another perspective on the history of South Africa portrays Mandela as an exemplary hero, but The Inheritors offers a more nuanced image. “Many Black South Africans now criticize Mandela for demanding too little from whites, who make up about 15% of the population but still own much of the wealth.” In the post-apartheid 1990s, the whites were still very powerful, and pushing too hard could have sabotaged the whole deal. It’s the typical tug-of-war between erasing the past and pursuing justice that is common in this type of political and societal transition. Reconciliation often requires foregoing justice, but it still leaves deep, unhealed wounds.

“It’s amazing how much Black South Africans not only seek material reparations, but also simply want to hear, ‘We’re sorry — we were wrong,’” said Fairbanks. “A lot of us think that putting an end to an unfair system requires some sort of material effort — a political consensus or an economic mission. But many Black South Africans long for an apology.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.