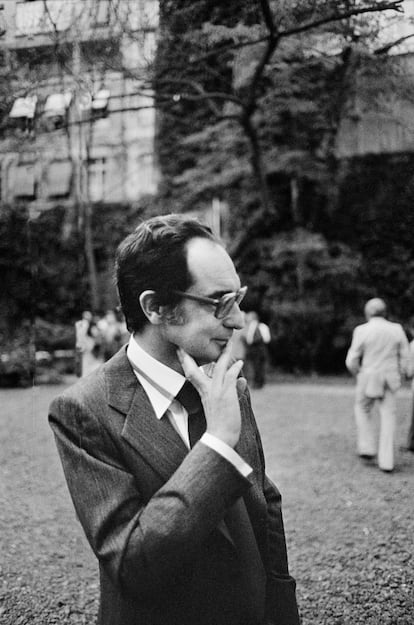

Italo Calvino, the writer who shrank the size of hell

The celebration of the author’s centenary reveals the enormous literary and intellectual stature of a man who always knew how to say ‘no’ when it came to the big red lines

At the beginning of The Baron in the Trees – one of his most famous works – Italo Calvino (1923-1985) narrates how the young Cosimo Piovasco di Rondò, while sitting at the family table for lunch, utters an extraordinary “no.” This is one of the most fantastic gestures of rejection of the state of things that can be found in world literature.

Urged by his parents to eat some snails, the future baron, who is 12 years old, replies: “I said I don’t want to and I don’t want to!” At his father’s insistence, Cosimo makes his disagreement even clearer: he decides to climb an oak tree outside the family villa. “You’ll see when you come down!” his father warns him. “Then I will never come down!” the boy replies. The reader is warned that he keeps his word.

Sometimes, when the answer is “no” – whether we pronounce it, or whether it stays in our throats – these moments can be the lighthouses that best guide our lives and our souls. This was certainly the case for Cosimo, and there’s reason to think that it was for Italo Clavino as well.

Like his character, the author – who would have turned 100 on October 15 of this year – also gave an emphatic “no” many times, exhibiting an indomitable independence. From this firmness sprung the literary and intellectual stature that makes him required reading. This firmness of opinion also turned him into a central cultural reference in the democratic and republican Italy that took shape during his lifetime. He was a favorite author, disciple, friend, editor or collaborator of Italian cultural icons such as Cesare Pavese, Elio Vittorini, Natalia Ginzburg, Carlo Levi, Leonardo Sciascia, Beppe Fenoglio, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Alberto Moravia and many others. He was most popular during the years he lived in Turin, a key city in the construction of thought in modern Italy.

First came the “no” to fascism, which led Calvino to take up arms in a communist partisan brigade. His first novel, The Path to the Nest of Spiders, emerged from his experience. He once said: “Resistance brought me into the world, even as an author.” Then came the “no” to Soviet communism, which led him to leave the Italian Communist Party in 1957. His serious political confrontations are reflected in The Baron in the Trees, which was published the same year. The writer refused to accept the Communist Party’s lukewarm stance in the face of the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956. In a farewell letter, published in the party’s official newspaper L’Unità, he regretted the lack of condemnation of “unacceptable methods of exercising power.”

Calvino’s literary path was also paved by several big “no’s.” Above all, he demonstrated a refusal to remain in familiar territory: he had an unwavering drive to explore new narrative landscapes. Under that impulse, he undertook a narrative journey of astonishing originality and internal diversity, visiting the shores of neorealism (The Path to the Nest of Spiders), the “lyrical-epic-buffoonish” narrative (the Our Ancestors trilogy, of which The Baron in the Trees is the second part), the “reflective narrative, in which story and essay merge into one (A Plunge into Real Estate), the “petits poèmes en prose” (Invisible Cities), the metanarrative (If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler) and other inventive genres.

Like his character Cosimo, Calvino, in a certain sense, circumvented the law of gravity. He was an unclassifiable writer who – paraphrasing two of his best-known metaphors – knew how, from a poetic lightness, to “slaughter monstrous jellyfish” (Six Memos for the Next Millennium) and “shrink hell, thanks to continuous attention and learning” (Invisible Cities).

The famous ending of Invisible Cities crystallizes his obstinacy, his refusal to accept the traditional and his willingness to build something new and better. It’s an open window that allows us to see the importance and validity of Calvino, both on the purely literary level and on the sociopolitical level. The most cited fragment is the following:

“The hell of the living is not something that will be. If there is one, it is what is already here, the hell we live in every day, that we make by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the hell, and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of hell, are not hell, then make them endure, give them space.”

Calvino searched a lot; he knew how to recognize who was (and wasn’t) hell. A key decision, in this respect, was his choice to settle in Turin after World War II, attracted by, as he would later say, a “moral and civil – and not literary – image” of the city. The capital of the kingdom that unified Italy, Turin was a strong center of legal, political and philosophical thought. Gramsci, Togliatti, Bobbio and Vattimo studied or taught there at different times – it was an incubator of a special experiment, that of interaction between high culture and the masses. As workers orbited around the Fiat factory and academics lectured at the University of Turin, the city gave wings to the intellectual and civil growth of the author.

Turin has been a powerful incubator of ideas for modern Italy. A prominent role, in this context, was played by the Einaudi publishing house, founded in the 1930s by Giulio Einaudi – the son of Luigi Einaudi, who would become the second president of the Republic — and which included writers Cesare Pavese and Leone Ginzburg (Natalia’s husband) among its great promoters. Precisely, the establishment of a very close relationship between Pavese and Calvino (before Pavese’s suicide in 1950) allowed Calvino to enter the Einaudi orbit. This facilitated his growth as an author, but also as a cultural driving force.

At Einaudi, Calvino also assumed the role of editor, establishing a rich correspondence with great Italian cultural figures. In this position, he also knew how to recognize what was not hell and give it space. Through the works he edited – as well as through his essays and articles – he contributed greatly to the establishment of the new post-fascist Italy.

Calvino was especially active during that fertile period in Turin. He was defined as militant, in every sense, with literary activism alongside Vittorini – with whom he would publish the important magazine Il Menabò – and with a strong propensity to speak out on political issues. But also in his “hermit” stage – during his prolonged residence in Paris – he continued to be a driving force, connected and influential nonetheless. “Above all, in the 1970s, I was a hermit. Off to the side… but not too far away,” he commented slyly. He would continue to influence and interact, like Cosimo, who, perched in his tree, not only cultivated love, but contributed to collective life. Calvino would continue to give space to what was not hell.

The quote at the end of Invisible Cities is frequently mentioned, but the author later reminded readers not to separate it from the passage that precedes it. “They quote the last lines – those referring to hell – while shortly before, there’s the passage of discontinuous utopia that gives meaning to the entire speech,” Calvino noted, in 1973. His fictitious version of Marco Polo tells Emperor Kublai Khan about the flashes of beauty that he sees, while suggesting that the perfect city is “made of fragments mixed with the rest, of moments separated from intervals.” We find here an invitation to search for truth and beauty everywhere, in space and time, without dogmatism or rigidity, with the mental openness that distinguished Calvino.

With lightness, speed, accuracy and multiplicity, Calvino established all the values for the new millennium in a series of lectures that he was supposed to give at Harvard. However, a few weeks before the scheduled date, in 1985, he suddenly died, at the age of 61.

A symbol of his open-mindedness was his affirmation that, while he opted for certain values, this didn’t diminish the validity of opposing ones. Calvino felt that, in life, there are big red lines that must be defended with extreme vigor if necessary… but he still said that it was wise to consider arguments and virtues from different points of view.

In that open-mindedness – in search of what was not hell, amidst fragments and moments of truth and beauty – Calvino pursued a borderless knowledge of matter and geography, very much in line with the Italian humanist tradition. “I would like to refer here to at least two things that I have believed in along my path and in which I continue to believe. One is the passion for a global culture… the rejection of the incommunicability of narrow specialization, to keep alive an image of culture as a unitary whole, in which every aspect of knowing and doing is a part. Another is the passion for political struggle, culture and literature, [towards] the formation of a new ruling class… I’ve always worked with that in mind: to see a new ruling class take shape and contribute to leaving an imprint,” he wrote, in a series of notes that were posthumously compiled in the book Hermit in Paris: Autobiographical Writings by Italo Calvino (1994).

This search for knowledge without borders led him to surprising results, from his concern about environmental pollution as early as 1958, when he published Smog, or his ability – at times truly incisive – to observe the future. “We’re on the eve of containing the universal consciousness in an electronic brain,” can be read in A Plunge into Real Estate (1957). And, in If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler (1979), he alludes to calculating machines that can complete any novel from beginning to end.

Although it’s less obvious, there’s another great link between Calvino’s work and the Italian literary tradition: the poetic vein. He declared that Italian literature is a “literature whose backbone is poetry, not so much prose,” with Eugenio Montale being his favorite author in that literary branch. While Calvino wasn’t a poet, he was the creator of a narrative full of poetry. “Invisible cities were born of poetry,” he wrote. Several times, he noted that his stories began with inspiring images; that they took shape when he brought those images to their ultimate form. In this poetic sense – as well as in the humanist sense – Calvino is a profoundly Italian author.

The very image of hell in Invisible Cities – the book that Calvino was most satisfied with, saying that he felt it was the “most polished” – contains a suggestive poetic and humanist connection with the great Italian poet Dante. There are at least two references of interest that can be considered. The first is when the travelling poet of the underworld sees “a light that conquered the hemisphere of darkness.” The great poets that Dante loved – Homer, Horace, Ovid and Lucan, who, together with Virgil, inhabit that place – immediately appear there. And the other Dantesque reference that can be considered also has to do with a burning flame. This time, it’s the spirit of Ulysses, who tells the poet about his end – how he exhorted his sailors to go beyond the pillars of Hercules. Dante’s immortal verses are present: “You were not made to live as brutes, but to follow virtue and knowledge.” Perhaps they influenced Calvino.

In a world that is petrified in the face of nationalist monstrosity – amidst hyper-partisan stupidity, in the daze of social media – it continues to be enriching to contemplate that flickering flame, the work of Italo Calvino, which, born of “no’s,” shrinks the darkness of hell that advances.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.