Formula 1, bankruptcy, grief and a marital crisis: New film narrates the most turbulent year in the life of Enzo Ferrari

The sports thriller ‘Ferrari’ – directed by Michael Mann – falls short of expectations, despite a star-studded cast consisting of Adam Driver and Penélope Cruz, as well as an adrenaline-pumping plot. Meanwhile, the action film ‘Dogman,’ by Luc Besson, surprised audiences at the Venice Film Festival

Sometimes, life suddenly speeds up. And humans — ever so fragile — can only run to catch up. Or, at least, to keep an eye on it, until it slows down again. Even Enzo Ferrari — a man quite accustomed to breakneck speeds — was shaken by what happened to him in 1957. The company of his dreams was on the verge of bankruptcy. His marriage was broken. His new romance, uncertain. And the absence of his son, Dino — who died at the age of 24 from muscular dystrophy — was a fresh wound. Too many problems for a single summer and a single man… but quite the opportunity for a movie.

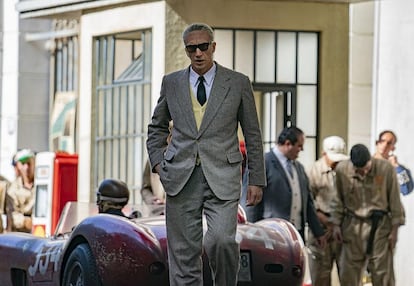

Ferrari — directed by Michael Mann and presented this past Thursday at the Venice Film Festival — narrates the most turbulent months of the founder of the famous car brand, who bet all or nothing to take back control of his existence. However, despite the high expectations, the film’s engine was less than impressive. At the other end of the competition, few believed in Dogman, by Luc Besso, but it has gained more fans since it’s screening.

A priori, Ferrari had all the elements needed to become an unstoppable favorite ahead of the awards season. It had the return of Mann, the filmmaker behind renowned movies such as Heat, Collateral and The Insider, who is an expert in creating rhythm, atmosphere and dialogue. It featured stars such as Adam Driver and Penélope Cruz. And it was telling the story of both a global and Italian legend. Going into its premiere, Ferrari had adrenaline, an exciting personal story, as well as “greed, loss, passion, ambition,” as Mann himself listed before reporters in Venice.

Fans waited near the red carpet from early in the morning, just for the chance to catch a glimpse of Driver at night. There was an endless queue to access the press conference. Everything indicated that the film was ready to make a speedy entrance. In the end, however, the feature film appeared to prefer the cruising speed of Fiat 500. Safe, reliable, a lesson in prudence, perfect for the road. But disappointing for those in the theater. There was none of the “lethal passion” that was promised.

“It’s a deeply human story. When you find a dynamic character like him, the more you dive [into him], the more universal he becomes. And, [in 1957], many of the issues that surrounded him — his past and his future — came together,” the director affirmed. Yet, among so many possible routes and risks, the film chose to take the most conventional highway. Only the handful of racing sequences have any adrenaline. Perhaps it is driving towards successful box office numbers, but it will still have to deal with the critics.

From an artistic point of view, it’s difficult to justify why the film renounced the real language (Italian) of its story. It’s clear that money was in charge and global distribution was front-of-mind. But with so many Italy-centric phrases pronounced in English, Ferrari loses credibility. At times, it even borders on the comic. This is despite the fact that Driver repeatedly stressed the importance of filming in the original locations, to absorb the native culture.

Mann spoke of “cultural anthropology” to summarize his approach and his research, based on the book Enzo Ferrari: The Man and The Machine, by Brock Yates. The director shared that his experience in amateur car races taught him something when filming them: “The focus is intensely on one object. Everything else disappears.” Driver stressed that he was more interested in the drivers — in their mentality, their instincts and the courage to risk their lives as they turned every corner. But the actor approached the cars only in fiction: “They didn’t let me drive them, for insurance reasons,” he joked. The press room was filled with laughter.

Shortly before he defended the film, the actor showed his support for the strike that screenwriters and actors have launched against the big studios and streaming platforms — the reason that prevented many of Driver’s famous colleagues from appearing at Venice: “I’m very proud to be a visual representation of a movie that’s not part of the AMPTP [Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers] and to promote the SAG [Screen Actors Guild] leadership directive.”

He also asked why a smaller distribution company — such as the one that put out Ferrari — “can meet the demands of what SAG is asking for, but a big company like Netflix and Amazon can’t?” This question has been hanging in the air for months as the strike carries on.

When it came to Dogman, it had been many years since French director Luc Besson delivered such a film. So much so that his arrival in the press room — alongside his star, Caleb Landry Jones — was celebrated with great applause. Of course, the positive reception will draw complaints by those who regret that the Venice Film Festival has given a space to a man who was previously accused of sexual violence. On three occasions, the French justice system refused to reopen an alleged rape case against the filmmaker, due to lack of evidence. However, several other complaints about inappropriate behavior by the director have been compiled by various media outlets.

In any event, nobody at the press conference asked Besson about his legal affairs. As the conversation turned to Dogman, he reflected on the origins of the story: “Since I was 16-years-old, I write every morning, starting at 5 a.m. When I read an article about a boy locked in a cage by his parents, I began to ask questions: what do you become [after that experience]? A terrorist, or Mother Teresa?”

Douglas — the movie’s protagonist — experiences the same torture as the boy that Besson read about. But, behind bars, he finds another kind of affection: that of dogs. Adding violence, love, Shakespeare and drag queens, Besson composes a fast-paced thriller, while knowing how to take a pause. At times, it’s unsettling — at other times, it moves you. The direction, the script and the acting have a lot of merit. And Landry Jones, who plays the lead, is already causing a stir for his performance.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.