How a heroin addict and a teenager uncovered a million-dollar scam

The HBO Max documentary series ‘Telemarketers’ sheds light on the fraudulent tactics of a company that pretended to collect donations and the efforts of two workers to expose them

Sometimes it’s hard to be civil with the stranger who interrupts our nap with a cold call. As soon as we answer, we have already hung up, without even bothering to find out what product they are trying to sell us. It is hard to imagine that these people, calling from some godforsaken cubicle in a nondescript building, could be the heroes of a story.

Two of these salesmen star in Telemarketers, an HBO Max documentary series released this month. It is a striking piece of citizen journalism that uncovers the criminal activities of Civic Development Group (CDG), the company responsible for one of the largest telemarketing scams in history. Since the early 1990s, the firm has raised money on behalf of charities and kept 90% of donations. The total amount is impossible to quantify, but it is estimated to be around $1 billion (€920 million).

The featured employees are two misfits, often under the influence of drugs, who recorded everything from the inside, armed with a camcorder and a bong. Their narrative style is unique but powerful. Years later, the material has been transformed into a series directed by Sam Lipman-Stern, one of the former workers, along with documentary filmmaker Adam Bhala Lough, and produced by the Safdie brothers, the creators of cult movies such as Good Time< /i> (2017) and Rough Diamonds (2019).

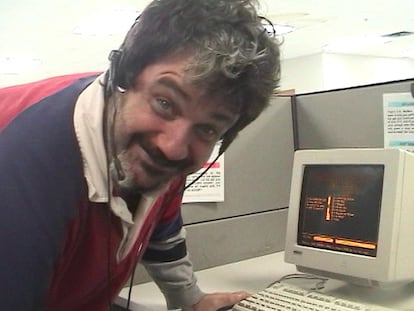

In 2001, Lipman-Stern, co-director of the film and one of the protagonists of this story, dropped out of high school and started looking for a job. He found only one company that agreed to hire him: CDG, an American telemarketing giant in the business of raising funds for charities. The office workspaces were arranged in cubicles. In each one of them was a telemarketer, staring at the monochrome screen of a tube computer. They wore a headset microphone and followed an instruction sheet stapled to one of the walls. The goal: to convince people on the other end of the line to donate money to supposed charitable causes like helping the police force, war veterans, or cancer patients.

According to the series, the work environment was always pure, crazy fun with minimal rules. It was nothing unusual to make a scene, flirt in the bathrooms, or race chairs in the office. The same went for drinking alcohol or taking cocaine in the rest area. Discretion was not a priority, neither towards the company nor amongst themselves. Most of the workers had gone to jail at one point or another. As one of the employees admits: “CDG was a place where they hired the people no one else would hire.” Recording the usual work environment and sharing it on YouTube seemed like a good idea to Lipman-Stern. “It was like a dysfunctional family,” he told Time recently. “You had a murderer on your right and a bank robber on your left. You can’t write characters like that.”

A singular hero

Amongst those characters was Pat Pespas, a telemarketing legend, who exudes a certain kind of charisma on screen. He is addicted to heroin, but at the same time, he is an efficient worker. He has impeccable morals and is a better salesman after using drugs. In one of the opening scenes, he takes a shot on his lunch hour and confidently returns to the switchboard to close a sale. It is he who, in a moment of amazing lucidity, recognizes his true role in the company before anyone else: “What we do is call people... and get their money.”

It is a precise definition of CDG’s fundamental business model. Founded in 1990, it kept a large part of the donations. Sometimes less than 10% went to charitable causes. The donors were unaware of all this. If they asked, the instructions posted on the wall advised lying and ensuring that the total proceeds went to the associations. “CDG looked like something out of a gangster movie,” says a worker on the series.

Lipman-Stern and Pespas found out. They decided to record the modus operandi of the company, not because of how exotic their coworkers were, but to accumulate evidence of the criminal tactics they were employing. “The model was based on hiring ex-cons and drug addicts because they are big hustlers,” says Lipman-Stern. “They know how to extort money from people, and they are not going to say anything about suspicious activity.” The success of the salespeople, who earned $10 an hour and received no commission, lay in their ability to sound credible over the phone. In the first episode, some workers mention that their bosses advised them to imitate the way the local police spoke: “Think about how the policemen sound in the cartoons and try to imitate them.”

The company was led by two sets of brothers: the Keezers and the Paschs. One of them was a musician in a Christian rock band. In 2010, the Federal Trade Commission (FT) fined the company $18.8 million (€17.4 million) for fraud and stopped its operations, although the Keezers and Pasch did not face criminal charges. The amateur sleuths warn us that once CDG was out of the game, other telemarketing companies copied their scam model. For this reason, with Pespas working as a Chinese food delivery man, they decided to continue their investigations.

Stoner movie

Watching these two social misfits attempt to follow in Michael Moore’s footsteps and expose the intricate webs of corruption in the world of telemarketing is captivating. It is also a spiritual redemption for Pat Pespas, who turns the series into the epic of an anti-hero in search of justice and also manages to beat his addictions. His effort to expose scandals veers from enthusiasm to clumsiness. They take advantage of their virtues as telemarketers — insistence and persuasion — to pull the thread and end up turning the documentary into a wonderful comedy of friends, which recalls different film genres.

Telemarketers almost sounds like a non-fiction stoner movie. This film subgenre focuses on the recreational use of cannabis, where marijuana acts as a central element or catalyst of the plot. It is renowned for having eccentric humor, characters who are carefree, and who often find themselves involved in bizarre or surreal situations, which themselves are the product of or influenced by their altered state under the influence of drugs.

There are some milestones of the genre, such as Up in Smoke (1978), an iconic film that narrates the adventures of the comic duo Cheech and Chong to get the best marijuana in California and, in a slightly more film noir vein, the Coen brothers’ The Big Lebowski (1998) and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Inherent Vice (2014) and Under the Silver Lake (2018).

The characters in Telemarketers do not limit themselves, but they bring together all the essential elements that define the genre. The only difference is that these characters do not come from the imagination of a scriptwriter. They resemble The Dude from The Big Lebowski in his positive outlook on the world. For Lipman-Stern, the story isn’t all bad: “CDG employed people who couldn’t get a job, from a 14-year-old graffiti artist to a person with an anxiety disorder,” he told Time. Then, he added that the story also reflects the generosity of thousands of people who wanted to contribute donations to charitable causes: “Non-profit organizations are amazing. It just wasn’t what we were doing.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.