Fentanyl’s butterfly effect: End of heroin boom leaves Mexican poppy farmers high and dry

Photographer César Rodríguez shines a light on the effect of market changes in the demand for illegal drugs on communities that survived by cultivating in the mountains of Guerrero

This is a story of globalization, capitalism and drugs, but also of hands gnarled by labor in the fields, lost harvests and dying communities: a story that can be traced from the subsistence farmers who grow poppies in the isolated mountains of Guerrero, Mexico, to the fentanyl addicts on the street corners of Los Angeles. In a world that is interconnected to the point of satiation, the chaos theory idea that the wings of a butterfly in Hong Kong can translate into a hurricane in New York extends to the most unexpected corners of reality. Hard drugs are no exception.

Fifteen years ago, photographer César Rodríguez became familiar with the mountains of Guerrero while working as an evaluator of indigenous shelters. Since then, he has not stopped going back. “It affected me a lot. I would go, take pictures, talk to people, get lost for a while,” he tells EL PAÍS over the phone. His camera was filled with snapshots of those places where poppy cultivation was the center of economic activity, but also of social and cultural life. A brown resin, called gum, is extracted from the flowers which, after drying, becomes heroin, a potent, addictive, and lethal drug that the United States and Canada consumed in vast quantities — 90% of the product originated in Mexico. For decades, trafficking to the other side of the border was the main source of income for these towns. Until the arrival of a new narcotic that began to displace heroin: fentanyl, a synthetic substance that is sweeping the streets of the United States and has sparked a serious public health crisis, as well as diplomatic tensions between Mexico, the White House and China. With the decline of heroin use came social decline. Communities broke up, money evaporated and the men migrated again in search of work. Rodríguez documented it all in Montaña Roja (or, Red Mountain), considered one of the best photography books of 2022 by the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

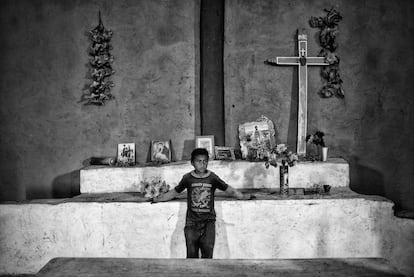

“They cultivate and harvest to survive. I wanted to focus on the people: the traditions, the way of life over there, their rituals. And I saw that everything revolves around the poppy: there are rituals for better rainfall; if there is better rainfall, the better the harvest; they ask priests to come and bless their fields; or they pray that the army doesn’t come and burn and cut down their fields; celebrations are paid for with poppy money; some people send their children to study with the proceeds of poppy money... The poppy is an economy for them,” says Rodríguez.

Montaña Roja is part of a larger project, an attempt to join the forces of academia and journalism to report on complex issues such as poppy production and fentanyl consumption. “From the beginning of our periods spent in the highlands, people were saying: ‘The Chinese are exporting a new drug and the gringos don’t want heroin anymore.’ Everyone told the same story. For a very long time in Mexico, people didn’t see this poppy crisis, but the farmers saw it very clearly; it was a kind of macroeconomic intuition. It is very interesting how information circulates in an illicit market, how information from the street in the United States ends up reaching the farmers in the Guerrero highlands,” says Romain Le Cour, co-founder of Noria, one of the centers involved in the research.

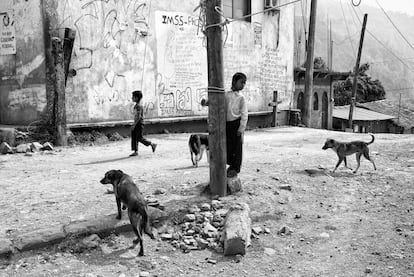

“What César tried to do in the book is to show that an illicit economy is completely embedded in everyday life,” continues Le Cour, who holds a doctorate in political science from Sorbonne University. Rodríguez’s photographs portray Guerrero in the leisurely poetry of black and white: dirt roads lost in the mist of the mountains; humble huts, shacks constructed with plastic and aluminum; stray dogs; white-haired women and faces lined with wrinkles in churches that are falling apart; peasants with drooping shoulders and weary faces, cut from the same cloth of jeans, sandals and hats; old, calloused hands, tanned by dust, sowing and harvesting, with the universal scars left by endless days of work in the fields; poppy fields in the solitude of the hillsides, their thin stems crowned by a ball that resembles a scepter.

“Poppies were almost a subsidy”

At the height of the heroin boom, the price of poppy gum in the U.S. was 30,000 pesos ($1,670) per kilogram. When the fentanyl boom arrived, the price dropped to 3,000 pesos ($167) per kilogram, a figure that is far from profitable for farmers. “People told us, ‘I have poppy fields, but no one buys my gum.’ There is this notion that drugs are the most profitable product in the world, that it is a recession-proof industry, but what is documented in this project is a quite unprecedented economic crisis surrounding a drug: it is a product that no longer sells because of a macro transformation of the market, in demand... it was hugely unfortunate for the farmers of Guerrero, Sinaloa, Nayarit, or Durango, who had been cultivating poppies for decades. It was their source of income,” says Le Cour.

The poppy, the academic explains, became “almost a subsidy. It sprung up, took hold, grew, expanded and in the highlands and mountains people even began to grow it in the backyards of their homes, more or less in plain sight, despite a quite discretionary repression of the trade by the army. One generation passed it down to the next and for a while emigration to the United States was limited to an extent by it. It allowed people to return to their communities, to invest in them, to send their children to college. It was a very strong subsidy in very poor areas, ones that had been abandoned by the state.”

But everything, eventually, comes to an end. Market forces managed to achieve what no politician had in 60 years: people stopped planting poppies. Without the poppy fields, income dried up. Inhabitants of the mountains began again to migrate north, to the U.S. or Mexican cities, to find work and send remittances home. Many were forced back into day labor, selling their days for miserable pay. “This led to serious impoverishment in communities that were already very poor. At the moment, we are not able to assess the impact, but there is an incredible opportunity to re-integrate these people into legitimate economies in exchange for a gift that the economy handed the Mexican government, by removing the poppy,” says Le Cour.

One hand, two bullets

Since Rodriguez first set foot in the mountains of Guerrero, the landscape has undergone changes. Now, many farmers leave the flowers to rot in the fields due to a lack of buyers. Others cling to a small uptick in prices. A few have already started the transition to avocado or lemon crops. The photographer tells the story of a man who, thanks to the poppy, was able to send his two eldest children to university. The third was not so lucky: he wanted to study computer science, but by the time he was old enough, his father’s savings were gone and he had to stay in the village and help with the harvest.

Violence also haunts these communities. Criminal groups that want to take control of the poppy business threaten the peace of the mountains. In the villages, self-defense groups have been formed by residents. “When we went there, the area was practically untouched by the cartels; they only went there to buy the product. But the last few times we were there the cartels were starting to exert their influence. The locals told us there is a village surrounded by other villages that are dominated by the cartel: they are shut off; the children don’t go to school because they are located in rival towns. There you are in apparent peace and suddenly you hear a bullet over there, gunfire coming from somewhere else,” says Rodriguez.

In the photographer’s book, there is an image that illustrates the problem. It is of an old hand, covered with dust, dirt between the fingernails. In the palm, it holds two bullets. The hand belonged to the leader of one of the self-defense groups. “A year after taking the photo, they killed him. It was very tough,” Rodríguez says. Not all the images conjure bad memories, however. “Some of the young people in the photos have migrated to California, and I plan to visit them to give them copies of the book. They are illegally employed and they send us memes and videos of them working in the strawberry fields.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.