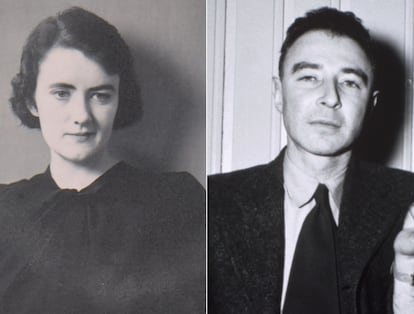

The tragic life of Jean Tatlock, the psychiatrist who rejected Oppenheimer

The release of Christopher Nolan’s film has brought the doctor, the great love of the father of the atomic bomb, back into the limelight. We review the influence the real Tatlock, played by Florence Hugh, had on the physicist’s career and her early and controversial death

It’s the big movie battle of 2023: Oppenheimer and Barbie, two of the most anticipated films of the year, opened simultaneously on the big screen to fight for much more than box office hegemony. Grayscale versus bright pink. Nolan versus Gerwig. Two antithetical films force the viewer to choose between the adult drama of dispatches and ethical dilemmas and the escapist feminist fantasy. Despite the clichés about its testosterone levels, Oppenheimer is much more than a biopic about the American physicist (played by Cillian Murphy) who ended up becoming the father of the atomic bomb. The thriller also narrates his tortuous relationship with psychiatrist Jean Tatlock, the most influential woman in Oppenheimer’s life, played by Florence Pugh. The young intellectual rebelled against the social conventions that restricted women at the time. Her early death is still the subject of theories and conspiracies today. Although many have tried to reduce her role to that of a mere mistress, the facts say otherwise. This is her tragic story.

Robert Oppenheimer met Tatlock during his tenure as a physics professor at UC Berkeley in California. He was good friends with her father, John, a renowned English professor on the faculty, and his 22-year-old, green-eyed, brown-haired firstborn daughter was already well known around the medical campus, where she was training to be a psychiatrist. The year was 1936, and to see a woman in a university classroom was still considered unusual, even more so one with Tatlock’s academic brilliance, life history — she had toured Europe studying psychoanalysis — and good looks. “We were all a bit jealous,” confirms a friend in the scientist’s biography. Despite the ten years’ difference that separated them, all of Oppenheimer’s close friends maintain that Oppenheimer fell in love with her as he never had before. “Jean was Robert’s truest love. He loved her more than anyone else. He was devoted to her,” said Robert Serber, a nuclear physicist and Oppie’s confidant. He proposed to Tatlock, unsuccessfully, at least twice.

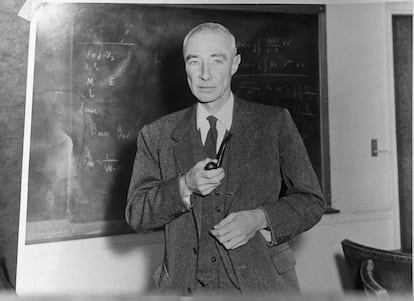

The young woman’s sympathy for the Communist Party brought great headaches to the couple. Tatlock was placed under FBI surveillance on suspicion that she might be a source of radicalization for Oppenheimer or even a Soviet spy. Even after the young woman’s death, the physicist continued to be forced to deny these claims in harsh interrogations before the U.S. government. “Her party affiliation was intermittent and never seemed to provide her with what she was looking for. I don’t think her interests were really political. She loved her country, her people and her life,” he testified at a government hearing. The paranoia went so far that the notorious and controversial J. Edgar Hoover, in charge of the intelligence bureau, had the psychiatrist’s apartment phone tapped and her every move tracked.

Jean Tatlock and Robert Oppenheimer broke off their relationship in 1939. A few months later, the scientist met Katherine Kitty Puening, a biologist who had been married twice before and soon became his wife and the mother of the couple’s two children. Despite being married, Oppenheimer continued to see Tatlock, who was beginning to suffer increasingly acute depressive episodes. It is said that the doctor’s mental state worsened after the loss of contact with her great love. On June 14, 1943, after he began directing the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos that would culminate in the creation of the atomic bomb, he returned to San Francisco to spend what would be his last day with her. Followed by Army officers without his knowledge, Oppenheimer met Tatlock at the train station and, after kissing, they spent the entire day together. Reports certify that they turned off the lights in the young woman’s apartment at 11:30 p.m. After breakfast together again, the doctor drove Oppie to the airport to return to the military compound.

On January 4, 1944, Tatlock’s father came to the apartment after Tatlock had not answered the phone for several days. After climbing through a window to gain access, he found his daughter dead, her head submerged in a half-filled bathtub. She was 29 years old. Next to her was a note that read: “I am disgusted with everything. To those who loved me and helped me, all love and courage. I wanted to live and to give, and I got paralyzed somehow. I tried like hell to understand and couldn’t... I think I would have been a liability all my life — at least I could take away the burden of a paralyzed soul from a fighting world.” Although the conspiracy theory regarding Tatlock’s alleged murder has been stoked for nine decades on purely speculative grounds, some proven facts fuel that fire.

Once the young woman’s inert body was found, John Tatlock took it upon himself to burn all of his daughter’s correspondence and images before calling the funeral services, supposedly to clear her of any suspicion of links to communism. The autopsy, which determined that the cause of death had been asphyxiation by drowning, also revealed that there were no traces of alcohol in her blood and that none of the barbiturates the psychiatrist had taken had reached her vital organs at the time of her death. A doctor with access to the details of Tatlock’s death confessed to the authors of the book American Prometheus, on which Christopher Nolan’s film is based, that “if you’re smart and you want to kill someone, this is the right way to do it.” Her brother Hugh Tatlock always supported the assassination theory.

Peter De Silva, a CIA officer in charge of security at Los Alamos, was in charge of informing Oppenheimer of Jean’s death. The scientist was devastated after the news and went for a long walk. “He said he didn’t have anyone else he could talk to anymore,” De Silva said. Robert Oppenheimer dubbed the first atomic bomb test Trinity. As those close to him recounted, the name is an homage to a poem by John Donne that Jean Tatlock shared with him.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.